Most analysts consider WWI a pointless conflict that resulted from diplomatic entanglements rather than some travesty of justice or aggression. Yet, it was catastrophic to a generation of Europeans, killing 14 million people.[i]

The United States joined this unnecessary war a few years into the hostilities, costing many American lives, even though the U.S. was not party to the alliances that had drawn other nations into the fray. This even though Americans had been strongly opposed to entering the war and Woodrow Wilson had won the presidency with the slogan, “He kept us out of war.”[ii]

President Wilson changed course in 1917 and plunged the U.S. into that tragic European conflict. Approximately 320,000 Americans were killed or injured.[iii] Over 1,200 American citizens who opposed the war were rounded up and imprisoned, some for years.[iv]

A number or reasons were publicly given for Wilson‘s change of heart, including Germany‘s submarine warfare, Germany’s sinking of the British passenger ship Lusitania,[v] and a diplomatic debacle known as the Zimmerman Telegram episode.[vi] Historians also add pro-British propaganda and economic reasons to the list of causes, and most suggest that a number of factors were at play.

While Americans today are aware of many of these facts, few know that Zionism appears to have been one of those factors. [Zionism was a political movement to create a Jewish state in Palestine. When this movement began, in the late 1800s, the population of Palestine was 96 percent Muslim and Christian. The large majority of Jews around the world were not Zionists.]

Diverse documentary evidence shows that Zionists pushed for the U.S. to enter the war on Britain’s side as part of a deal to gain British support for their colonization of Palestine.

From the very beginning of their movement, Zionists realized that if they were to succeed in their goal of creating a Jewish state on land that was already inhabited by non-Jews, they needed backing from one of the “great powers.”[vii] They tried the Ottoman Empire, which controlled Palestine at the time, but were turned down (although they were told that Jews could settle throughout other parts of the Ottoman empire and become Turkish citizens).[viii]

They then turned to Britain, which was also initially less than enthusiastic. Famous English Middle East experts such as Gertrude Bell pointed out that Palestine was Arab and that Jerusalem was sacred to all three major monotheistic faiths.[ix]

Future British Foreign Minister Lord George Curzon similarly stated that Palestine was already inhabited by half a million Arabs who would “not be content either to be expropriated for Jewish immigrants or to act merely as hewers of wood and drawers of water for the latter.”[x]

However, once the British were embroiled in World War I, and particularly during 1916, a disastrous year for the Allies in which there were 60,000 British casualties in one day alone,[xi]Zionists were able to play a winning card. While they previously had appealed to religious or idealistic arguments, now Zionist leaders could add a particularly powerful motivator: telling the British government that Zionists in the U.S. would push America to enter the war on the side of the British, if the British promised to support a Jewish home in Palestine afterward.[xii]

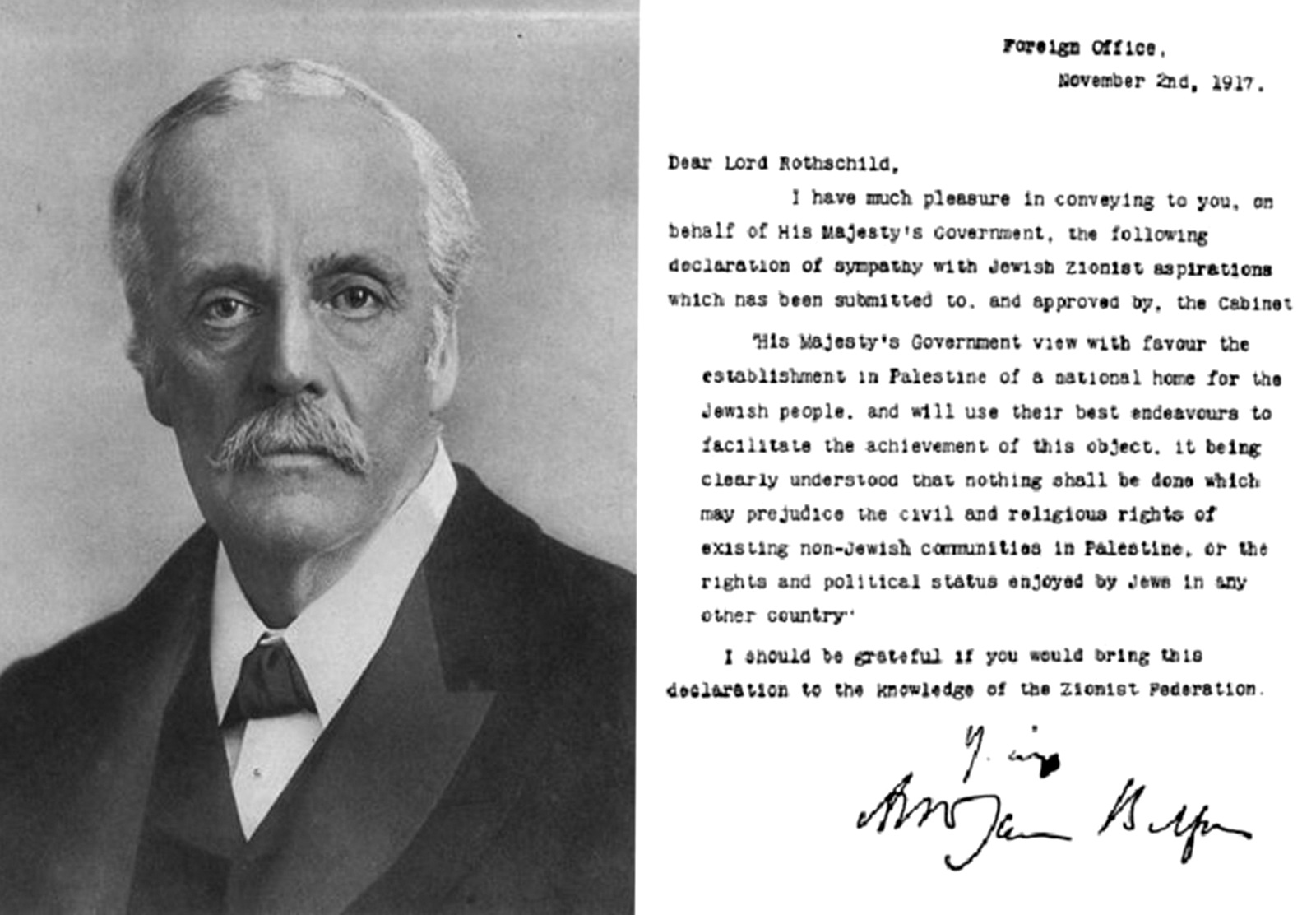

In 1917 British Foreign Minister Lord Balfour issued a letter to Zionist leader Lord Rothschild. Known as the Balfour Declaration, this letter promised that Britain would “view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” and “use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object.”

The letter then qualified this somewhat by stating that it should be “clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” The “non-Jewish communities” were 92 percent of Palestine’s population at that time,[xiii] vigorous Zionist immigration efforts having slightly expanded the percentage of Jews living in Palestine by then.

The letter, while officially signed by British Foreign Minister Lord Balfour, had been in process for two years and had gone through a number of edits by British and American Zionists and British officials.[xiv] As Zionist leader Nahum Sokolow later wrote, “[e]very idea born in London was tested by the Zionist Organization in America, and every suggestion in America received the most careful attention in London.”[xv]

Sokolow wrote that British Zionists were helped, “above all, by American Zionists. Between London, New York, and Washington there was constant communication, either by telegraph, or by personal visit, and as a result there was perfect unity among the Zionists of both hemispheres.” Sokolow particularly praised “the beneficent personal influence of the Honourable Louis D. Brandeis, Judge of the Supreme Court.”[xvi]

The final version of the Declaration was actually written by Leopold Amery, a British official who, it came out later, was a secret and fervent Zionist.[xvii]

It appears that the idea for such a declaration had been originally promoted by Parushim founder Horace Kallen. [The Parushim was a secret Zionist society described by professor Sarah Schmidt and U.S. author Peter Grose; for more information and citations see Weir’s book.]

Author Peter Grose reports, “The idea had come to [the British] from an unlikely source. In November 1915, long before the United States was involved in the war, the fertile brain of Horace Kallen… had come up with the idea of an Allied statement supporting in whatever veiled way was deemed necessary, Jewish national rights in Palestine.”

Grose writes that Kallen suggested the idea to a well-connected British friend who would pass the idea along. According to Kallen, such a statement “would give a natural outlet for the spontaneous pro-English, French, and Italian sympathies of the Jewish masses.” Kallen told his friend that this would help break down America’s neutrality, which Kallen knew was the aim of British diplomacy, desperate to bring the U.S. into the war on its side.

Grose writes: “Kallen‘s idea lit a spark of interest in Whitehall.”[xviii]

While the “Balfour Declaration” was a less than ringing endorsement of Zionism, Zionists considered it a major breakthrough, because it cracked open a door that they would later force wider and wider open. In fact, many credit this as a key factor in the creation of Israel.[xix]

These Balfour-WWI negotiations are referred to in various documents.

Samuel Landman, the secretary of the World Zionist Organization, described them in detail in a 1936 article in World Jewry. He explained that a secret “gentleman’s agreement” had been made in 1916 between the British government and Zionist leaders:

After an understanding had been arrived at between Sir Mark Sykes and [Zionists] Weizmann and Sokolow, it was resolved to send a secret message to Justice Brandeis that the British Cabinet would help the Jews to gain Palestine in return for active Jewish sympathy and for support in the USA for the Allied cause, so as to bring about a radical pro-Ally tendency in the United States.[xx]

Landman wrote that once the British had agreed to help the Zionists, this information was communicated to the press, which he reported rapidly began to favor the U.S. joining the war on the side of Britain.[xxi]

Landman claimed that Zionists had fulfilled their side of the contract and that it was “Jewish help that brought U.S.A. into the war on the side of the Allies,” thus causing the defeat of Germany.[xxii] He went on to state that this had “rankled” in Germany ever since and “contributed in no small measure to the prominence which anti-Semitism occupies in the Nazi programme.”

British Colonial Secretary Lord Cavendish also wrote about this agreement and its result in a 1923 memorandum to the British Cabinet, stating: “The object [of the Balfour Declaration] was to enlist the sympathies on the Allied side of influential Jews and Jewish organizations all over the world… [and] it is arguable that the negotiations with the Zionists…did in fact have considerable effect in advancing the date at which the United States government intervened in the war.”[xxiii]

Former British Prime Minister Lloyd George similarly referred to the deal, telling a British commission in 1935: “Zionist leaders gave us a definite promise that, if the Allies committed themselves to giving facilities for the establishment of a national home for the Jews in Palestine, they would do their best to rally Jewish sentiment and support throughout the world to the Allied cause. They kept their word.”[xxiv]

Brandeis University professor and author Frank E. Manuel reported that Lloyd George had testified in 1937 “that stimulating the war effort of American Jews was one of the major motives which, during a harrowing period in the European war, actuated members of the cabinet in finally casting their votes for the Declaration.”[xxv]

American career Foreign Service Officer Evan M. Wilson, who had served as Minister-Consul General in Jerusalem, also described this arrangement in his book Decision on Palestine. He wrote that the Balfour declaration “…was given to the Jews largely for the purpose of enlisting Jewish support in the war and of forestalling a similar promise by the Central Powers [Britain’s enemies in World War I]”.[xxvi]

The official biographer of Lloyd George, author Malcolm Thomson, stated that the “determining factor” in the decision to issue the Balfour Declaration was the “scheme for engaging by some such concession the support of American Zionists for the allied cause in the first world war.”[xxvii]

Similarly, Zionist historian Naomi Cohen calls the Balfour Declaration a “wartime measure,” and writes: “Its immediate object was to capture Jewish sympathy, especially in the United States, for the Allies and to shore up England’s strategic interests in the Near East.” The Declaration was pushed, she writes, “by leading Zionists in England and by Brandeis, who intervened with President Wilson.”[xxviii]

Finally, David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel, wrote in 1939: “To a certain extent America had played a decisive role in the First World War, and American Jewry had a considerable part, knowingly or not, in the achievement of the Balfour Declaration.”[xxix]

[Most Jews in the U.S and elsewhere, including in Palestine itself, were not Zionists, and some strenuously opposed Zionism. See the book for more information on this.]

The influence of Brandeis and other Zionists in the U.S. had enabled Zionists to form an alliance with Britain, one of the world’s great powers, a remarkable achievement for a non-state group and a measure of Zionists’ by-then immense power. As historian Kolsky states, the Zionist movement was now “an important force in international politics.”[xxx]

American Zionists may also have played a role in preventing an early peace with the Ottoman Empire.[xxxi]

In May 1917 American Secretary of State Robert Lansing received a report that the Ottomans were extremely weary of the war and that it might be possible to induce them to break with Germany and make a separate peace with Britain.[xxxii]

Such a peace would have helped in Britain’s effort to win the war (victory was still far from ensured), but it would have prevented Britain from acquiring Palestine and enabling a Jewish state.[xxxiii]

The State Department considered a separate Ottoman peace a long shot, but decided to send an emissary to pursue the possibility. Felix Frankfurter became part of the delegation and ultimately persuaded the delegation’s leader, former Ambassador Henry J. Morgenthau, to abandon the effort.[xxxiv]

US State Department officials considered that Zionists had worked to scuttle this potentially peace-making mission and were unhappy about it.[xxxv] Zionists often construed such displeasure at their actions as evidence of American diplomats’ “anti-Semitism.”

Top photo | Lord Balfour visits Hebrew University in Tel Aviv in April, 1925. (Photo: US Library of Congress)

Footnotes

(We suggest people read the full book, Against Our Better Judgment: The Hidden History of How the U.S. Was Used to Create Israel, for additional information.)

A number of links provided in the book’s citations now seem to be broken, so we have added archived versions where possible.

[i] “Overview of World War I,” Digital History, accessed January 1, 2014, http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraid=12&smtid=1.

[ii] “Woodrow Wilson.” The White House, accessed January 1, 2014, https://web.archive.org/web/20140102081625/https://www.whitehouse.gov/about/presidents/woodrowwilson

[iii] Over 116,000 Americans died and about 204,000 were injured.

“Military and Civilian War Related Deaths Through the Ages,” Tom Philo, accessed January 1, 2014, http://www.taphilo.com/history/war-deaths.shtml. https://www.pbs.org/greatwar/resources/casdeath_pop.html

[iv] Wilson‘s Espionage and Sedition Acts resulted in the jailing 1,200 American citizens.

“Walter C. Matthey of Iowa was sentenced to a year in jail for applauding an anticonscription speech. Walter Heynacher of South Dakota was sentenced to five years in Leavenworth for telling a younger man that ‘it was foolishness to send our boys over there to get killed by the thousands, all for the sake of Wall Street.’…Abraham Sugarman of Sibley County, Minnesota, was sentenced to three years in Leavenworth for arguing that the draft was unconstitutional and remarking, ‘This is supposed to be a free country. Like Hell it is.’”

Bill Kauffman, Ain’t My America: the Long, Noble History of Antiwar Conservatism and Middle American Anti-imperialism (New York: Metropolitan, 2008), 74.

One of the songs that helped recruit Americans to fight in the war, “Over There,” was written by George M. Cohan, who received the Congressional Medal of Honor for it in 1940, when America was about to join another world war.

“Who’s Who – George M Cohan,” First World War, August 22, 2009, http://www.firstworldwar.com/bio/cohan.htm

[v] The fact that the Lusitania was carrying munitions, a charge made by Germany at the time and since corroborated by divers going to the wreck, was largely suppressed for many years.

Few people are aware that the Lusitania was being used by the British as a high-speed munitions carrier. On her final voyage she was carrying even more contraband than usual, including eighteen cases of fuses for various caliber artillery shells and a large consignment of gun-cotton, an explosive used in the manufacture of propellant charges for big-gun shells. (“Deadly Cargo” http://www.lusitania.net/deadlycargo.htm)

Stolley, Richard B. “Lusitania: The Epic Battle over Its Biggest Mystery.” Fortune May 5 (2015): n. pag. Web. 11 May 2015. http://fortune.com/lusitania-gregg-bemis-legal-battle/. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/lusitania.htm, http://www.divernet.com/home_diving_news/156070/ordnance_found_aboard_lusitania.html

Germany had warned Americans not to ride on the Lusitania. The Library of Congress reports: “The German Embassy published a warning in some newspapers to tell passengers that travel on Allied ships is “at their own risk.” The Lusitania is mentioned specifically in some of the discussion about the warning in the week leading up to its departure.” (“Topics in Chronicling America – Sinking of the Lusitania.” Sinking of the Lusitania. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/rr/news/topics/lusitania.html.

For a discussion of events leading up to the U.S. entry into the war see Windchy, Eugene G. “Chapter 12 World War I (1917 to 1918).” Twelve American Wars: Nine of Them Avoidable. Bloomington, IN: IUniverse, 2014 According to Wilson’s top advisor, even after the Lusitania sinking, 90 percent of Americans were opposed to entering the war.

[vi] Some intriguing articles speculate that Zionists might have played a role in making the Zimmerman note public. While the article is speculative, the editors called it “…an original and very plausible explanation of a major event in world history for which no previous rationale has ever seemed satisfactory.”

John Cornelius, “The Balfour Declaration and the Zimmermann Note,” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, August-September (1997): 18-20. Print. Online at http://www.wrmea.org/component/content/article/188-1997-august-september/2646-the-balfour-declaration-and-the-zimmermann-note-.html, http://www.wrmea.org/2005-november/special-report-the-hidden-history-of-the-balfour-declaration.html

[vii] Shlaim, The Iron Wall, 5.

[viii] John W. Mulhall, CSP, America and the Founding of Israel: an Investigation of the Morality of America’s Role (Los Angeles: Deshon, 1995), 50.

Hala Fattah, “Sultan Abdul-Hamid and the Zionist Colonization of Palestine: A Case Study,” accessed January 1, 2014,

[ix] Paul Rich, ed., Iraq and Gertrude Bell‘s The Arab of Mesopotamia (Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2008), 150.

[x] Mulhall, America, 66.

This was a sadly deft prognosis. Writing of Jerusalem in the early 1960s, the American Consul General in Jerusalem found: “I think I can safely make the general comment that in present-day Israel… the Arabs are very much of ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’” for the dominant Israelis.

Evan M. Wilson, Jerusalem, Key to Peace (Washington: Middle East Institute, 1970), 33.

A number of other British officials also opposed Zionism. Charles Glass writes: “The only Jewish member of the British cabinet, Edwin Samuel Montagu, the secretary of state for India, argued against issuing the Declaration. Montagu called Zionism “a mischievous political creed” and wrote that, in favouring it, “the policy of His Majesty’s Government is anti-semitic.” David Alexander, president of the Board of British Jews, Claude Montefiore, president of the Anglo-Jewish Association, and most Orthodox rabbis also opposed the Zionist enterprise. They insisted that they had as much right as any Christian to live and prosper in Britain, and they did not want Weizmann, however Anglophile his tastes, telling them to settle in the Judean desert or to till the orange groves of Jaffa. The other opponents of a British protectorate for the Zionists in Palestine were George Nathaniel Curzon, leader of the Lords and a member of the war cabinet, and the senior British military commanders in the Middle East, Lieutenant-General Sir Walter Congreve and General Gilbert Clayton. The generals contended that it was unnecessary to use Palestine as a route to Iraq’s oil and thought that the establishment of the protectorate would waste imperial resources better deployed elsewhere.”

Charles Glass, “The Mandate Years: Colonialism and the Creation of Israel,” Guardian, May 31, 2001, http://www.theguardian.com/books/2001/may/31/londonreviewofbooks/print.

[xi] The BBC history of the Battle of the Somme reports that on the first day alone Britain sustained 60,000 casualties, of whom 20,000 were already dead by the end of the day; 60 percent of all officers involved had been killed. The battle went on for four and a half months.

“Battle of the Somme: 1 July – 13 November 1916,” BBC History, accessed January 1, 2014, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwone/battle_somme.shtml

[xii] A number of authors refer to this; see the following citations.

One was William Yale in The Near East: A Modern History (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1968), 266-270.

Yale, a descendant of the founder of Yale University, was an authority on the Middle East who had worked for the State Department in a number of roles in the Middle East, including as a member of the King Crane Commission, and worked for many years as a professor of history.

“Guide to the William Yale Papers, 1916-1972,” University of New Hampshire Library, accessed on January 1, 2014, http://www.library.unh.edu/special/index.php/william-yale.

https://web.archive.org/web/20131217122455/http://www.library.unh.edu/special/index.php/william-yale

Yale writes: “…the Zionists in England set about winning British support for Zionism. This the English Zionists successfully did by the end of 1916. It was an amazing achievement which required great skill, unfaltering energy, and determination. The methods by which the conquest of the British government was made were diverse and of necessity in some cases devious.”

He writes, “The Zionists in England well understood that British leaders would have to be approached on the basis of their interests and ideas,” and notes, “The means used were adapted admirably to the personal outlook and characteristics of the men to be influenced.”

Some were “persuaded that Zionism was a fulfillment of Old and New Testament prophesies.” Zionists also appealed to “the idealisms of many [British],” convincing them that this was a solution to anti-Semitism and could be an “atonement by Christian Europe for its long persecution of the Jews.”

Some top officials had to be persuaded “that Zionism was a noble and righteous cause of significance to the welfare of the world as well as to that of the Jewish people.”

Others were to be convinced that “by backing Zionism world-wide enthusiastic Jewish support for the allied cause could be assured.” Yale notes that in 1916 “the Allied cause was far from bright” and quotes a Zionist leader’s statements that Zionists worked to persuade British officials that “the best and perhaps the only way (which proved to be so) to induce the American President to come into the war was to secure the cooperation of Zionist Jews by promising them Palestine, and thus enlist and mobilise the hitherto unsuspectedly powerful forces of Zionist Jews in America and elsewhere in favor of the Allies on a quid pro quo contract basis. Thus, as will be seen, the Zionists, having carried out their part, and greatly helped to bring America in, the Balfour Declaration of 1917 was but the public confirmation of the necessarily secret ‘gentlemen’s’ agreement of 1916…”

Yale states that once “inner circles of the British government had been captured by the Zionists,” they turned their efforts to obtain French, Italian, and American acquiescence to the Zionist program.

In 1903, Zionists retained future Prime Minister Lloyd George‘s law firm.

For a detailed discussion of the Lusitania incident and other aspects of the U.S. entry into WWI see John Cornelius, “The Hidden History of the Balfour Declaration,” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, November 2005, 44-50. Print. Online at http://www.wrmea.com/component/content/article/278-2005-november/8356-special-report-the-hidden-history-of-the-balfour-declaration.html.

[xiii] McCarthy, Population of Palestine, 26.

[xiv] J.M.N. Jeffries, Palestine: The Reality, reprint ed (London: Longman, Greens, and Co, 1939), 172.

“Drafts for it travelled back and forth, within England or over the Ocean, to be scrutinized by some two score draftsmen half-cooperating, half competing with one another…”

Jeffries also reports that American Zionist leader Rabbi Stephen Wise wrote, “The Balfour Declaration was in process of making for nearly two years.”

[xv] Jeffries, Palestine: The Reality, 172. (Jeffries quotes Nahum Sokolow‘s History of Zionism)

[xvi] Nahum Sokolow, History of Zionism (1600-1918) with an Introduction by the Rt. Hon. A. J. Balfour, M.P., vol. 2 (London: Longmans, Green and Co, 1919), 79-80. Online at https://archive.org/details/historyofzionism02sokouoft.

Some of those involved in drafting the text were Brandeis, Frankfurter, and Wise. See:

“Along with Louis Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter, [Rabbi Stephen] Wise helped write the Balfour Declaration of 1917.” – Boxerman, Burton A. The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. By Anne Cipriano Venzon. New York: Routledge, 2012. 800:

Rabbi Stephen “Wise acted as an important intermediary to President Woodrow Wilson and Colonel Edward House from 1916-1919, when, with Louis D. Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter, he helped formulate the text of the Balfour Declaration of 1917.” – A Finding Aid to the Stephen S. Wise Collection. 1893-1969. Manuscript Collection No. 49. AmericanJewishArchives.org. The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, http://americanjewisharchives.org/collections/ms0049/:

[xvii] “Balfour Declaration Author Was a Secret Jew, Says Prof,” JWeekly, January 15, 1999, http://www.jweekly.com/article/full/9929/balfour-declaration-author-was-a-secret-jew-says-prof/.

William D. Rubinstein, “The Secret of Leopold Amery,” History Today 49 (February 1999). Online at http://www.ifamericansknew.org/us_ints/amery.html

According to his publisher, Macmillan, “William D. Rubinstein is Professor of Modern History at the University of Aberystwyth, UK and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. He has published widely on modern British history and on modern Jewish history, and was President of the Jewish Historical Society of England, 2002-2004. His works include A History of the Jews in the English-Speaking World: Great Britain (Palgrave Macmillan 1996), The Myth of Rescue (1997), and Israel, the Jews and the West: The Fall and Rise of Antisemitism (2008).”

“William D. Rubinstein,” Macmillan.com, accessed January 1, 2014, http://us.macmillan.com/authordetails.aspx?authorname=williamdrubinstein.

https://www.amazon.com/Palgrave-Dictionary-Anglo-Jewish-History/dp/1403939101

Amery, who had kept his Jewish roots secret, worked for Zionism in a number of ways. As a pro-Israel writer Daphne Anson reports:

“As assistant military secretary to the Secretary of State for War, Amery played a pivotal role in the establishment of the Jewish Legion, consisting of three battalions of Jewish soldiers who served, under Britain’s aegis, in Palestine during the First World War and were the forerunners of the IDF. ‘I seem to have had my finger in the pie, not only of the Balfour Declaration, but of the genesis of the present Israeli Army’, he notes proudly.

“As Dominions Secretary (1925-29) he had responsibility for the Palestine Mandate, robustly supporting the growth and development of the Yishuv – Weizman recalled Amery‘s ‘unstinting encouragement and support’ and that Amery ‘realized the importance of a Jewish Palestine in the British imperial scheme of things more than anyone else. He also had much insight into the intrinsic fineness of the Zionist movement’. In 1937, shortly after testifying before the Peel Commission on the future of Palestine, Amery helped to organise a dinner in tribute to the wartime Jewish Legion at which his friend Jabotinsky was guest of honour. Amery became an increasingly vociferous critic of the British government’s dilution of its commitments to the Jews of Palestine in order to appease the Arabs, and fulminated in the Commons against the notorious White Paper of 1939, which set at 75,000 the maximum number of Jews to be admitted to Palestine over the ensuing five years. ‘I have rarely risen with a greater sense of indignation and shame or made a speech which I am more content to look back upon’, he remembered. And he became an arch-critic of Chamberlain and Appeasement.”

Daphne Anson, “The Mosque-Founder’s Nephew who drafted the Balfour Declaration – Leopold Amery, the ‘Secret Jew,’” Daphne Anson blog, November 1, 2010, http://daphneanson.blogspot.com/2010/10/mosque-founders-nephew-who-drafted.html.

[xviii] Grose, “Brandeis, Balfour, and a Declaration,” 39.

Historian Ronald Sanders also discusses Kallen‘s role, writing, “…in the first half of December 1915, the Foreign Office received a memorandum that had been passed along a chain of contacts by its author Horace Kallen, a prominent American Zionist and a professor of philosophy at the University of Wisconsin.” In it Kallen had written, according to Sanders, “…I am convinced that a statement on behalf of the Allies favoring Jewish rights in very country… and a very veiled suggestion concerning nationalization in Palestine would more than counterbalance German promises in the same direction…”

Sanders writes that a week later Lucien Wolf, a prominent British journalist and Jewish leader, also sent a letter to the Foreign Office promoting the idea of working to propagandize American Jews so that they would work to bring the U.S. into the war on the side of Britain. In his communication Wolf claimed: “That such a propaganda would be very useful is evidenced by the fact that in the United States the Jews number over 2,000,000 and their influence–political, commercial and social–is very considerable.”

Wolf emphasized that he himself was not a Zionist, but recommended that working through the American Zionist movement would be the best way to achieve this purpose: “…in any bid for Jewish sympathies today, very serious account must be taken of the Zionist movement.”

He wrote, “The Allies, of course, cannot promise to make a Jewish State of a land in which only a comparatively small minority of the inhabitants are Jews, but there is a great deal they can say which would conciliate Zionist opinion.” He suggested that British statements of sympathy “with Jewish aspirations in regard to Palestine” could be decisive, concluding, “I am confident they would sweep the whole of American Jewry into enthusiastic allegiance to their cause.”

Sanders points out that Wolf‘s statement, “coming as it did from the spokesman of the foreign policy organ of the Anglo-Jewish establishment,” seemed to the Foreign Office “as official a statement of the Jewish view of the matter as they had ever received.”

Sanders, a Jewish-American author who has written several books about both Israel and Jewish Americans, writes that while the general British belief about the power of Jews in America “was greatly exaggerated, it certainly was not groundless.” According to Sanders, in 1915 the American Jewish community was becoming one of the most “financially gifted subgroups” in the American population and notes, “Some of the country’s greatest newspapers were owned by Jews.” He also describes the importance of Brandeis, “who was to be appointed to the United States Supreme Court in January 1916, just as the Foreign Office was pondering these very questions…”

Ronald Sanders, The High Walls of Jerusalem: A History of the Balfour Declaration and the Birth of the British Mandate for Palestine (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984), 323-330.

Another person is reported to have also promoted the plan that Britain should work with American Zionists, Brandeis in particular, as a way to bring America into the war on England’s side. James Malcolm, an Armenian-Persian who was close to the British government, wrote about his role in this beginning in autumn of 1916 in a booklet published in 1944 by the British Museum, Origins of the Balfour Declaration, Dr. Weizmann‘s Contribution. Online at http://www.mailstar.net/malcolm.html.

Malcolm‘s role and others’ were discussed in a July 1949 exchange of letters to the editor in The Times of London. One of these is online at http://www.ifamericansknew.org/download/thomson-jul49.pdf.

More information on this topic is available in “The Zionism of James A. Malcolm, Armenian Patriot,” by Martin H. Halabian, a thesis submitted for a Master’s degree from the Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies at Brandeis University in May 1962.

See also footnote 78 below.

[xix] For example, Grose writes, “The promise of a Jewish national home in Palestine opened the way for the partition of Palestine, and, thereby, for Israel’s statehood.” (Grose, “Brandeis, Balfour, and a Declaration,” 39)

[xx] John and Hadawi, Palestine Diary, 72. Citation: World Jewry, March 1, 1935.

[xxi] Samuel Landman, “Great Britain, the Jews and Palestine,” New Zionist (London), 1936. Online at http://desip.igc.org/1939sLandman.htm.

Excerpts below:

“Mr. James A. Malcolm, who….. knew that Mr. Woodrow Wilson, for good and sufficient reasons, always attached the greatest possible importance to the advice of a very prominent Zionist (Mr. Justice Brandeis, of the U.S. Supreme Court) ; and was in close touch with Mr. Greenberg, Editor of the Jewish Chronicle (London) ; and knew that several important Zionist Jewish leaders had already gravitated to London from the Continent on the qui vive awaiting events ; and appreciated and realised the depth and strength of Jewish national aspirations; spontaneously took the initiative, to convince first of all Sir Mark Sykes, Under Secretary to the War Cabinet, and afterwards Monsieur Georges Picot, of the French Embassy in London, and Monsieur Goût of the Quai d’Orsay (Eastern Section), that the best and perhaps the only way (which proved so. to be) to induce the American President to come into the War was to secure the co-operation of Zionist Jews by promising them Palestine, and thus enlist and mobilise the hitherto unsuspectedly powerful forces of Zionist Jews in America and elsewhere in favour of the Allies on a quid pro quo contract basis. Thus, as will be seen, the Zionists, having carried out their part, and greatly helped to bring America in, the Balfour Declaration of 1917 was but the public confirmation of the necessarily secret ‘gentleman’s’ agreement of 1916…”

“The Balfour Declaration, in the words of Professor H. M. V. Temperley, was ‘a definite contract between the British Government and Jewry.’ The main consideration given by the Jewish people (represented at the time by the leaders of the Zionist Organisation) was their help in bringing President Wilson to the aid of the Allies.”

“…many wealthy and prominent international or semi-assimilated Jews in Europe and America were openly or tacitly opposed to it (Zionist movement)…”

“In Germany, the value of the bargain to the Allies, apparently, was duly and carefully noted.”

“The fact that it was Jewish help that brought U.S.A. into the War on the side of the Allies has rankled ever since in German – especially Nazi – minds, and has contributed in no small measure to the prominence which anti-Semitism occupies in the Nazi programme.”

[xxii] Landman, “Great Britain, the Jews and Palestine.”

[xxiii] Lawrence Davidson, America’s Palestine: Popular and Official Perceptions from Balfour to Israeli Statehood (Gainesville: UP of Florida, 2001), 11-12.

Lloyd George had been retained as an attorney by Zionists in 1903. While not yet a government leader, he was already a Member of Parliament.

[xxiv] Mulhall, America, 62.

[xxv] Frank E. Manuel, “Judge Brandeis and the Framing of the Balfour Declaration” in From Haven to Conquest, by Walid Khalidi (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1987), 165-172.

He also writes that, according to de Haas, “American Zionists were responsible for a final revision in the text of the declaration.” (Manuel, “Judge Brandeis,” 71)

[xxvi] Evan M. Wilson, Decision on Palestine: How the U.S. Came to Recognize Israel (Stanford: Hoover Institution, Stanford University, 1979), xv.

Moshe Menuhin, scion of a distinguished Jewish family that moved to Palestine during the early days of Zionism (and father of the renowned musicians), also writes about this aspect. In addition, he states that the oft-repeated claim that the British rewarded Weizman for his “discovery of TNT” was false, quoting Weizmann‘s autobiography Trial and Error:

“For some unfathomable reason they always billed me as the inventor of TNT. It was in vain that I systematically and repeatedly denied any connection with, or interest in, TNT. No discouragement could put them off.”

Moshe Menuhin, The Decadence of Judaism in Our Time (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1969), 73-74.

[xxvii] Malcolm Thomson, “The Balfour Declaration: to the editor of the Times,” The Times(London), November 2, 1949, 5. Online at http://www.ifamericansknew.org/images/thomson-nov49.png.

He also wrote about this in a July 22, 1949 letter to the editor in The Times; see earlier footnote.

[xxviii] Cohen, Americanization of Zionism, 37.

[xxix] Ben-Gurion, “We Look Towards America,” Jewish Observer and Middle East Review (January 31, 1964), 14-16. Excerpted in Khalidi, From Haven to Conquest, 482.

Ben Gurion is widely lauded as Israel’s main founder. While there is no doubt that he was an extremely zealous and committed promoter of Zionism, Ben Gurion was also, according to historian Norman Kantor, “a bit of a crook.” Kantor writes that Ben Gurion “dipped into Histadrut funds for his own personal use, including trysts with his mistress in sundry European spas.” –Sacred Chain, p. 368

[xxx] Kolsky, Jews against Zionism, 12.

[xxxi] This section is taken largely from the following sources:

Henry Morgenthau and Peter Balakian, Ambassador Morgenthau‘s Story (Detroit: Wayne State UP, 2003), 370.

Grose, “Brandeis, Balfour, and a Declaration,” 37.

Yale, Near East, 241.

Jehuda Reinharz, “His Majesty’s Zionist Emissary: Chaim Weizmann‘s Mission to Gibraltar in 1917,” Journal of Contemporary History 27, no. 2 (1992): 259-277. Online at http://www.jstor.org/stable/260910.

The U.S. never declared war on the Ottoman Empire and was working as a mediator in this venture.

[xxxii] Grose, “Brandeis, Balfour, and a Declaration,” 37.

[xxxiii] Reinharz, “His Majesty’s Zionist Emissary,” 263.

[xxxiv] Morgenthau was not a Zionist, but he agreed to accept Frankfurter, then a 35-year-old Harvard law professor, as his traveling companion. (Historians speculate that Brandeis suggested Frankfurter.) Frankfurter then chose the rest of the entourage, almost all of whom were ardent Zionists. The British dispatched Zionist Chaim Weizmann (who was alerted to the mission by Brandeis and others) to meet with the Morgenthau mission in Gibraltar. Frankfurter and Weizmann persuaded Morgenthau not to move forward with the initiative.

Reinharz writes: “It is possible that Brandeis, unable to oppose the scheme himself, insisted on Weizmann as the most likely person able to derail the Morgenthau mission.” (Reinharz, “His Majesty’s Zionist Emissary,” 267)

Reinharz also states: “Obviously Felix Frankfurter also reported to Louis Brandeis that it was due to Weizmann that Morgenthau‘s mission had failed. On 8 October 1917, Brandeis cabled to Weizmann: ‘It was a great satisfaction to hear yesterday from Professor Frankfurter fully concerning your conference [at Gibraltar] and to have this further evidence of your admirable management of our affairs.’” (Reinharz, “His Majesty’s Zionist Emissary,” 273)

Charles Glass writes: “Wilson sent Morgenthau to Switzerland to meet Turkish representatives. But American Zionists opposed this move, as Thomas Bryson explained in American Diplomatic Relations with the Middle East 1784-1975 (1977). It seems that the U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis knew the purpose of the Morgenthau mission and told Weizmann, who promptly alerted Balfour. According to Bryson, ‘the two agreed that the Morgenthau mission should be scotched, for an anticipated British offensive against the Turks in Palestine would do far more to assure the future of a Jewish national home. Brandeis arranged for Felix Frankfurter‘ – his clerk and later a Supreme Court justice – ‘to accompany Morgenthau to ascertain that the latter would not make an agreement compromising the Zionist goal. Acting through Balfour, the Zionists arranged for Morgenthau and Frankfurter to meet Dr Weizmann at Gibraltar, where he deterred Morgenthau from his task.’”

Glass, “The Mandate Years.”

[xxxv] Grose, “Brandeis, Balfour, and a Declaration,” 37

![]() If Americans Knew is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.

If Americans Knew is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.