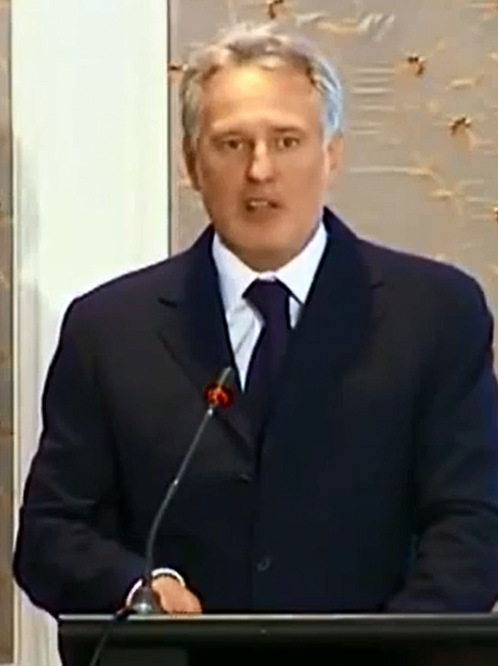

On March 13, Ukrainian gas tycoon Dmytro Firtash, believed to be one of Ukraine’s richest men and most influential oligarchs, was arrested in Vienna, Austria. He was released on March 21 after posting bail of 125 million euros ($174 million), but he still faces possible extradition to the United States, where he is wanted by the FBI on suspicion of corruption and forming a criminal organization.

“The charges result from an investigation, which the FBI has conducted for several years, of an alleged international corruption conspiracy,” according to an FBI press release from March 14. “Firtash’s arrest is not related to recent events in Ukraine.”

Firtash’s legal representation issued a statement from Firtash, saying that he strongly believes the motivations behind his arrest were “purely political” and “without foundation.”

All of this has raised a number of questions. Who is Firtash? And why is the FBI after him?

Who is Dmytro Firtash?

Few people would have heard about Firtash prior to his arrest in Austria. According to his website, he was born on May 2, 1965, in Ukraine. He graduated from Krasnolimansk Railway Vocational School and later received a degree from the National Academy of Internal Affairs of Ukraine. After serving in the military from 1984 through 1986, he started in business.

Like many Ukrainian — and Russian — oligarchs, or business magnates with strong political influence, he appeared suddenly on the economic scene after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the independence of Ukraine in the early 1990s, starting with almost nothing and quickly building up wealth and influence during the country’s transition to a market-based economy.

He founded his own trading company, established commercial ties in Central Asia and organized food supplies to this region in exchange for natural gas. In 2004, Firtash and the Russian state-controlled gas monopoly, Gazprom, jointly established RosUkrEnergo, a company to distribute natural gas in Ukraine and the European Union. He later set up an international group of companies, Group DF, with core areas of operations in fertilizer and titanium businesses, gas distribution and banking, as well as other businesses such as agribusiness, media, energy infrastructure and real estate.

Firtash started gaining recognition outside Ukraine in 2006, when RosUkrEnergo obtained a monopoly on all gas sold from Russia to Ukraine.

The arrangement was abolished in 2009 under the controversial gas contract signed by Yulia Tymoshenko, then-Ukrainian prime minister, and Vladimir Putin, then-Russian prime minister, with the aim of abolishing all intermediaries in the murky gas trade between the two countries. Later, Tymoshenko was condemned to a seven-year jail sentence after being convicted of abusing her office in relation to this contract.

In addition to his business dealings, the Ukrainian oligarch has also demonstrated a philanthropic side. In 2008, Cambridge University received $6.7 million from Firtash to launch a Ukrainian studies program “aimed at promoting the study of Ukraine’s rich cultural heritage in the United Kingdom and beyond.” In 2010, another donation made possible the permanent establishment of two key academic posts: a Lecturer in Ukrainian Studies and a Lector in Ukrainian Language.

Does he have a political side?

Although he claims he is not a member of any political party or movement, he is believed to have been close to ousted Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych. He has also been portrayed as one of the main lobbyists of Russian interests in Ukraine.

This may explain a move that surprised many: in October 2013, Russia offered Kiev a gas discount, selling directly to Ostchem, a company owned by Firtash, thereby bypassing Naftogas, the Ukrainian national gas and oil company. The gas discount was interpreted as part of Russia’s intensifying quest to convince Ukraine not to sign an Association Agreement with the EU at that year’s summit in Vilnius, Lithuania.

Due to its geographic position between oil- and natural gas-producing Russia and oil- and natural gas-consuming European countries, Ukraine, indeed, has a strategic importance in the world of energy. According to EU statistics from 2010, a large percentage of energy imported by European countries originates in Russia, including about 35 percent of crude oil and about 32 percent of natural gas. And a large portion of Russian oil and gas bound for Western Europe passes through Ukraine.

In other words, the EU relies heavily on Russia and Ukraine for its energy supply. Twice in the past decade — in 2006 and 2009 — Russia has turned off natural gas shipments to Ukraine during disputes over gas prices, which also affected some European countries. Thus, a gas deal between Russia and Ukraine — no matter the intermediary — clearly helps secure Europe’s energy supply.

Who are his connections?

Still, this doesn’t explain Dmytro Firtash’s arrest. The FBI’s arrest warrant mentions an “international corruption conspiracy,” but more precise details are scarce. The only more concrete information is that in 2010, there were reports alleging Firtash’s connection with the alleged Russian organized crime boss, Semyon Mogilevich. According to diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks, Firtash reportedly admitted to these ties during talks with the U.S. ambassador in Kiev, William Taylor, in 2008, explaining that he had sought permission from Mogilevich in the process of establishing a business.

Firtash also explained that it was impossible to approach a government official back in the early 1990s without also meeting with an organized crime member because of the lawlessness that reigned in Ukraine after the collapse of the Soviet Union. He denied having any close relationship with Mogilevich, but acknowledged that he needed and received permission from Mogilevich to establish various businesses, as it would have been otherwise impossible to do so.

While the U.S. considers Mogilevich a leading mafia boss — he is on the FBI’s list of the Ten Most Wanted Fugitives — and refers to a “multi-million dollar scheme to defraud thousands of investors in the stock of a public company incorporated in Canada, but headquartered in Newtown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, between 1993 and 1998,” there is no reference to Firtash’s involvement.

It is a well-known fact that after the fall of Soviet Union, what came to be known as oligarchs in Russia and Ukraine acquired their wealth mainly though corruption. And because of how they acquired their wealth, their slates may not be entirely clean. In this sense, Firtash would not be an exception.

Many oligarchs are free to travel and live as they please. Some have even invested considerably abroad, especially in the United Kingdom, as Firtash did with his donations to Cambridge. According to the Economist, the amount of money that oligarchs have pumped into those countries means that the U.K. government will find it hard to crack down on them. In reality, it seems that as long as they don’t commit too obvious a crime in a Western jurisdiction or don’t directly threaten European or American interests, the oligarchs are relatively safe.

Nor is Firtash on the list compiled by the E.U. early this month – following the crisis over the referendum organized in Crimea – of people whose assets were frozen due to suspicions that they had misused state funds or violated human rights.

Why does the FBI want him?

His two bodyguards in Vienna did not prevent Austrian police from arresting him. The FBI has been on Firtash’s heels for almost eight years, investigating his potential involvement in starting an organized crime syndicate.

Firtash’s Group DF, based in Switzerland, confirmed that his arrest was triggered by an investment project he started in India in 2006, as reported by various news sources.

Until the FBI releases more details, however, there may not be conclusive answers to all of the questions surrounding Dmytro Firtash.