JERUSALEM — “I need a cell for a Jew,” the Israeli cops driving the jeep called into the jail. I was the Jew they were referring to and the jail was the infamous “Muskobia,” in the heart of West Jerusalem. This was the end of a long and tiring day that began with a protest in the village of Nabi Saleh in Palestine. I was covered in sweat, tear gas, dust, and quite a bit of the disgusting skunk liquid that the Israeli army sprays on protestors.

It was a hot day and my arms were full of bruises, my elbow and wrists sprained from the soldiers twisting them during the arrest. But regardless of the fact that I was protesting with Palestinians, I was still a Jew and when I was sent to jail for the night the authorities needed to make sure I was in a cell for Jews.

White privilege it seems, like skin color, doesn’t go away even in situations like that. Not that the cell for Jews was a room at the Marriott — far from it. There were eight or ten other guys, it was so full of cigarette smoke that I could hardly see from one end of the cell to the other, and when one of the inmates called for help because he was sick the guards showed no concern whatsoever.

However, I knew that my visit in the cell was limited to 24-48 hours at the very most. I knew that I would see a judge by the end of the first 24 hours and that a lawyer was on my case before I even reached the police station. It goes without saying that my interrogation was in a police station in the local settlement, not in a Shabak, or secret-police dungeon.

My rights were read to me and I was offered coffee and even a sandwich. I was not blindfolded, I was not beaten, I wasn’t shackled, and it took a while for the soldiers who brought me in to realize that they had forgotten to take away my cell phone, which of course I used to inform my family and friends where I was during several visits to the restroom.

All this took place several years ago. What I had learned from years of crossing the line from the privileged side to the side of the wall where privilege is not available, is that no amount of activism and no amount of crossing this line can take away the white privilege.

It wasn’t until recently that a chink was made in the armor of white privilege. Just a chink, and barely noticeable to the naked eye.

A “Fringe Member” of the Jewish Community: How Hasbara Trolls Reacted to My Campus Appearance

Secondary security screening

Landing in Washington, Dulles Airport after a recent visit to Palestine, I hurried, as I always do, to the Global Pass line. Global Pass is a privilege one can utilize that allows for a quick and easy entry back to the U.S. To receive it you must complete an extensive form, pay, and go through an interview at a local Homeland Security office. I have had this wonderful privilege for many years and it makes life a lot easier when I travel.

However, upon this recent return, something had changed. After placing my passport in the machine, I received a piece of paper telling me to see an agent. The agent took my passport, placed it in a sealed box, and told me to take it to another room. “Follow the red tape on the floor,” he said.

The line led me to another agent at the entrance to a large hall. He took my passport and sent me to sit and wait in a particular part of the hall. That is when it occurred to me that I was actually going through secondary security screening. This trip was not an ordinary one. It was May of 2021, my first trip to Palestine since COVID, and it was prompted by the unusual uprising that had taken place in Palestine.

No flights were landing in Tel-Aviv because the airlines were afraid of the Qassam rockets being shot from the Gaza Strip. So even though my ticket was to Tel-Aviv, I was rerouted and flew to Istanbul; then to Amman, Jordan; and from there I proceeded overland to cross into Palestine — a process that is neither pleasant nor convenient and consumes an entire day. My return to the United States was the same. I had to travel overland to Amman, Jordan, and from there to fly via Istanbul to Washington.

As I was sitting in the secondary-screening hall I was pondering all of this and wondered if that was the reason for the ordeal. In front of me were tables where passengers placed their luggage for inspection. On one of them, a Black woman had her suitcase and handbag and an officer was going through each and every item. When he finished inspecting the most intimate parts of her private possessions he looked at her. The woman was obviously pregnant and the officer asked, “Is the father your husband or your boyfriend?”

What town in Jerusalem are you from?

I have been questioned enough times to know that things are not going well when the officer looks at your passport and asks you questions for which the answers are written in the passport itself. “Where were you born?” “What countries did you visit?” This is why there is a passport to begin with, so that an officer can see the answers to those questions at a glance.

“I was born in Jerusalem,” I said, as it is stated in my passport.

“Yes, but what town or city in Jerusalem?” he asked.

“Jerusalem is a city.”

“Oh ok, well I am not familiar with the region.

“What countries have you visited in the last few years?”

The list was long but the one that he found most interesting was Iran. He asked a few questions about what I did and where I went, and what I spoke about during my lectures.

“Peace, love, and reconciliation,” I replied.

After the questioning came the inspection of my belongings, every item and every piece of paper was examined and had to be explained.

The entire affair took a couple of hours. It wasn’t pleasant, but it was not the end of the world. What did seem to me to be the end of the world was the email I received the following day, notifying me that my Global Pass was revoked as well as my TSA Pre-Check.

So now, with a chink in my privilege, each time I fly I must wait in line with everyone else, pull out my laptop and, what is worst of all, take off my shoes.

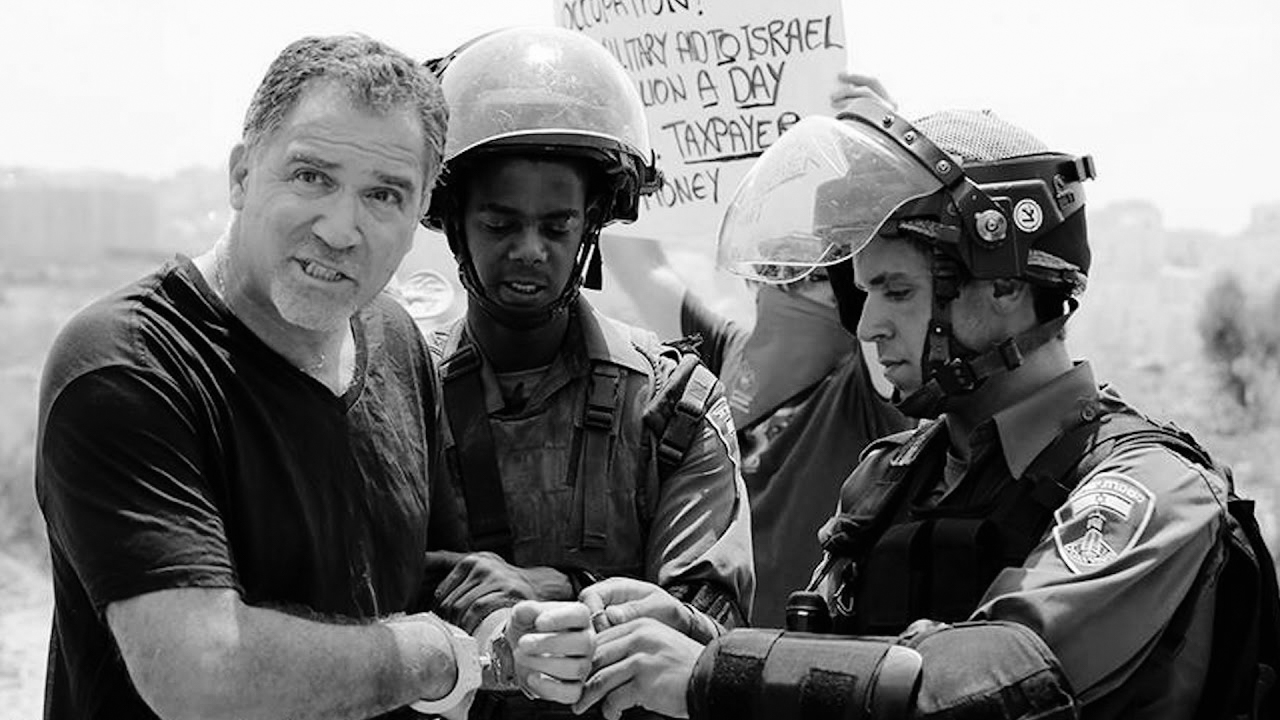

Feature photo | This undated screenshot taken from a video shows the arrest of Miko Peled by Israeli forces during a protest in occupied Palestine.

Miko Peled is MintPress News contributing writer, published author and human rights activist born in Jerusalem. His latest books are”The General’s Son. Journey of an Israeli in Palestine,” and “Injustice, the Story of the Holy Land Foundation Five.”