BARINAS, VENEZUELA — In the Venezuelan state of Barinas, the U.S.-backed opposition candidate for governor won an election on Sunday, January 9. Sergio Garrido – who has openly supported the fake “interim” presidency of Juan Guaidó, recognized only by the U.S. and 15 other world governments – defeated the Venezuelan government candidate, Jorge Arreaza, 55% to 41%.

The Barinas gubernatorial election on January 9 was actually a rerun. Twenty-three states chose governors on November 21, 2021. Additionally, 335 mayors, 253 regional legislators, and 2,471 local councilors were elected. Overall, the elections were swept by the government. Nineteen of the 23 governorships were won by the Maduro government’s PSUV Party.

Barinas, like other states, voted in November. But this election had particular symbolic importance as it took place in the home state of the late President Hugo Chávez, mentor to current President Nicolás Maduro and founder of the political movement that has dominated Venezuelan electoral politics since 1998.

Rather than prompt the Western media to challenge Washington’s line that Venezuela is a dictatorship, or ask whether U.S. sanctions interfere in Venezuela’s elections, Garrido’s victory in Barinas had no impact on media coverage that constantly adopts the U.S. government’s perspective.

An AP report released the day after the opposition’s decisive win in Barinas said that “moves in Barinas raised further doubts about the fairness of Venezuela’s electoral system.” Win or lose, Maduro’s government is depicted as undemocratic and unpopular. Nearly identical versions of the AP article appeared in The Washington Post and Toronto Star.

The AP stated explicitly that the “U.S.-backed” opposition prevailed in Barinas thanks to voters being “angry over a lack of basic services like gas, water and electricity, deficient health care services and hunger from food scarcity.” But the U.S. has “backed” the opposition precisely by imposing sanctions designed to produce the hardships that AP described. The AP article failed to make that point or even mention U.S. sanctions.

In the U.S., alleged hacking of Democratic National Committee emails by Russia is considered scandalous and intolerable election interference. In Venezuela, massive U.S.-imposed economic sabotage is ignored, and, even after a U.S.-backed candidate wins an election, complaints by seditious candidates are highlighted as grave concerns. The AP said that “Billboards and other advertisements for Arreaza could be seen across the state, and to a lesser extent, those of [Claudio] Fermin’s campaign. But Garrido’s advertising presence was virtually nonexistent.”

It’s worth imagining Russia imposing starvation sanctions on the U.S., but the U.S. still allowing openly Russian-backed candidates to run in elections. Now imagine those candidates being allowed to win, but still complaining about a lack of “advertising presence.”

Opposition divisions

November’s vote count in the Barinas governor election was suspended by the Venezuelan Supreme Court after a complaint was filed by opposition politician Adolfo Superlano, who is with an anti-Guaidó faction. He has the same last name but is no relation to the opposition candidate Freddy Superlano, who ended up being disqualified by the court on the grounds that there were unresolved proceedings against him that had been initiated by the auditor general before the election. Freddy Superlano was projected to win by 0.39% when the count was stopped.

Evidence that opposition infighting played a role in getting the first Barinas election annulled was completely ignored by the Western media. That’s rather striking because it was widely acknowledged that a divided opposition allowed the PSUV to sweep the elections, despite getting less than half the vote (46%) nationwide.

Serious opposition divisions are inevitable when one faction, led by Guaidó, endorses the U.S.-led economic strangulation of its own country as a strategy to seize power. To call the U.S. sanctions illegal election interference would be a gross understatement; they are acts of war.

U.S. sanctions on Venezuela since 2017 have been linked to tens of thousands of deaths. UN special investigator Alfred De Zayas said U.S. sanctions on Venezuela should be investigated by the International Criminal Court. Another UN investigator, Alena Douhan, reported that sanctions have slashed the Maduro government’s revenues by 99%.

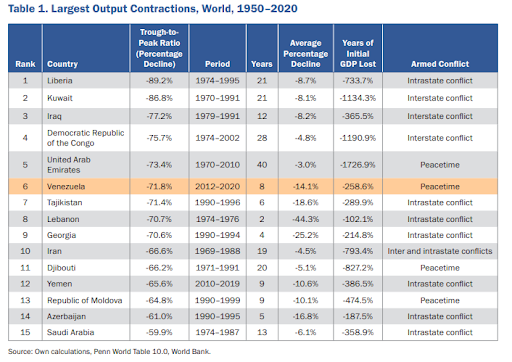

Francisco Rodriguez, an anti-Maduro Venezuelan economist, recently produced a very detailed rebuttal of arguments that attempt to dismiss the impact of U.S. sanctions. The economic losses in Venezuela are worse than those experienced during military conflicts in most countries since 1950. In fact, I disagree with Rodriguez classifying Venezuela as being under “peacetime” conditions in the table below. Since 2017, Maduro has had as much justification to call himself a wartime president as any U.S. president has had in the past 100 years.

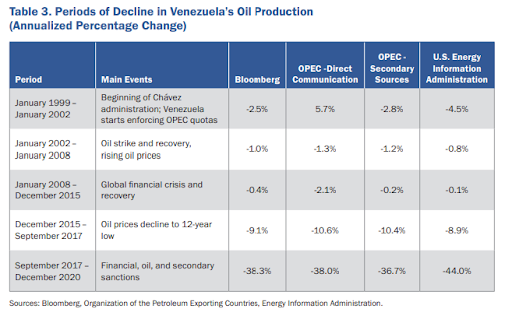

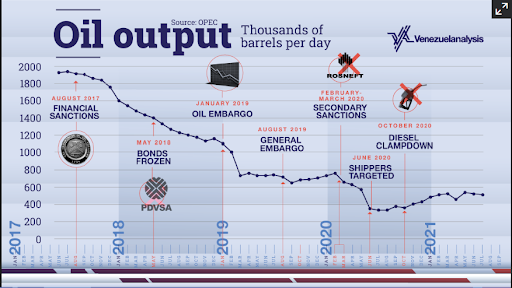

In 2017, then-President Donald Trump dramatically intensified the economic sanctions imposed by Barack Obama in 2015. The lethal impact since then on the oil production that sustains Venezuela’s economy could hardly be more obvious. The table below, showing oil production trends, is also taken from Rodriguez’s most recent work refuting apologists for U.S. sanctions. To put it another way, the table reveals devastating “election interference” of a kind that only Western reporters could miss.

Imperial assumptions

In the AP article about the Barinas vote, the issue of election interference was raised: the Atlanta-based Carter Center was cited denouncing the “interference” of Venezuela’s Supreme Court annulling the first Barinas election. The Carter Center also claimed that a “general atmosphere of political repression” existed. Turning to reality, Guaidó has not even been arrested in Venezuela for openly colluding with a foreign power’s efforts to overthrow the government. Fortunately for the Carter Center, Western reporters avoid sources that would ridicule such statements.

Similarly, Reuters uncritically reported claims that in recent elections a “fair vote” was “impossible because of interference from Maduro.” U.S. sanctions were then mentioned, but Reuters apparently found nobody to argue that sanctions are, to put it way too mildly, election interference.

In a report about the opposition’s win on Sunday, a Guardian subhead read: “Regime suffers symbolic blow as little-known Sergio Garrido secures victory in Barinas governorship election.” The word “regime” is also used in the text of the article by Guardian Latin America correspondent Tom Phillips.

Why does the Guardian give Maduro’s government the “regime” label while not bestowing it on the U.S.? Maduro is not devastating the U.S. economy in an effort to overthrow Biden. Shouldn’t the aggressor, not the victim, get the pejorative description? (See “A Regime Is a Government at Odds With the U.S. Empire.”) Phillips casually mentioned that Guaidó is “the leader of the failed U.S.-backed campaign to topple Maduro.” Phillips did not mention U.S. sanctions at all (i.e., no acknowledgment of the lethal nature of Guaidó’s “U.S.-backed campaign”).

Phillips used the term “farcical” to describe the annulment of November’s Barinas election. To the imperial mind, it isn’t “farcical” that Guaidó is not locked up in a Venezuelan jail – no matter how much he deserves to be, given his collaboration with a foreign power that has greatly harmed his own country. The reason Guaidó, and many of his allies, are free could not be more obvious: the U.S. is still powerful enough to give itself impunity, and that usually extends to allies. When murderous U.S. allies are jailed, like a former U.S.-backed dictator of Bolivia, it is then that Western journalists detect a problem.

Phillips also wrote that recent elections in Venezuela, held on the schedule established in the Venezuelan Constitution, were “designed to help Maduro regain international legitimacy.” But Maduro never lost international legitimacy, unless you assume that the U.S. and the minority of governments that support its aggression against Venezuela constitute the international community.

In October 2020, 105 UN states voted Maduro’s government onto the UN Human Rights Council in defiance of U.S. pressure. More recently, on December 8, 2021, as reported by Venezuelanalysis.com, “Guaidó only managed to get 16 countries at the General Assembly to vote against the recognition of the Maduro government as the legitimate representative of Venezuela.”

There have been six major U.S.-backed efforts to overthrow Venezuela’s democratically elected government since 2002 (see “Extraordinary Threat,” which I co-wrote with Justin Podur, published by Monthly Review Press). The Guiadó era can be thought of as one long and incredibly brutal sixth effort that began when Trump recognized Guaidó in January 2019. The recognition of Guiadó was the legal pretext to further intensify U.S. sanctions.

Partisan sources cited as if neutral

So often over the past twenty years, the Western media has vilified Venezuela’s government by quoting biased sources but presenting them as neutral and credible, and at the same time ostracizing independent sources that would offer a conflicting perspective.

The widely recycled AP article about the opposition’s win in Barinas cited the European Union electoral mission’s assessment that November’s elections in Venezuela were “held under better conditions than other ballots in recent years but were still marred by ‘structural deficiencies.”

But European Union election monitors parroted the now utterly discredited OAS assessment of the October 2019 presidential election in Bolivia. The OAS baselessly impugned an election and thereby helped incite a military coup that installed a right-wing U.S.-backed dictatorship for nearly a year. That’s quite a “deficiency” to overlook in the track record of European Union election monitors. Of course, it’s a deficiency Western media shared, and it took the admirable persistence of the Washington-based Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), and numerous other independent election experts who backed them up, to finally break through a media blackout on what both OAS and EU election monitors did.

Similarly, The Guardian, Financial Times, and Irish Times quoted former journalist Phil Gunson, now a “Venezuela analyst” with the International Crisis Group, in articles about the Barinas election of January 9. Gunson has been lampooning and vilifying Venezuela’s Chavista governments for two decades.

Months before a U.S.-backed military coup briefly ousted President Hugo Chávez in April 2002, Gunson wrote an article for Newsweek headlined “But Is [Chávez] Really Mentally Unbalanced?” A few years later, Gunson made strenuous, though ineffective, efforts to discredit the Irish documentary “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” which exposed how the Venezuelan and international private media propagandized in support of that coup and the ensuing short-lived dictatorship of Pedro Carmona.

Regarding Sunday’s election in Barinas, Gunson was quoted by the Guardian:

They [Maduro’s government] made sure there was petrol at the filling stations. They were handing out fridges and cookers and cement and doing all the things that they haven’t done in the last 22 years – and they absolutely, totally failed.”

U.S. sanctions have been openly aimed at emptying Venezuela’s filling stations and starving the country’s ability to feed itself. The U.S. has even been lawless and cruel enough to seize Iranian fuel shipments bound for Venezuela in 2020. Assuming what Gunson said is true – that the Maduro government’s efforts to offset U.S. economic sabotage were not enough to turn the electoral tide in Barinas – it takes a nasty imperial mind to delight in that failure. But that mentality is all too common among Western journalists.

Feature photo | Opposition governor-elect of Barinas state, Sergio Garrido, is surrounded by the press as he leaves a Mass the day after elections in Barinas, Venezuela, Jan. 10, 2022. Matias Delacroix | AP

Joe Emersberger is a Canadian engineer and UNIFOR member with Ecuadorian roots. He writes primarily for Telesur English and Znet.