In February 2011, then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates stated at West Point that “any future defense secretary who advises the president to again send a big American land army into Asia, or into the Middle East or Africa, should have his head examined.” While blood was spilled in Libya by NATO coalition forces, killing hundreds from the sky and giving cover for religious extremists to kill thousands, Gates’ advice was arguably taken and military engagement has been stretched thin, quietly and discreetly, especially in Africa.

One of the new War-on-Terror projects the Obama Administration inherited from the Bush Administration was the United States Africa Command, or AFRICOM. By the time Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016, AFRICOM had grown into a $250 million behemoth. Much of AFRICOM policy consists of training local forces with a focus on “counter-terrorism.” Jessica Piombo, editor of The US Military in Africa: Enhancing Security and Development? writes, “[T]he U.S. military has attempted to create new programs that involve a range of government and nongovernment actors in security programs that focus on more than training and equipping African militaries.”

In 2018, the administration declared interest in downsizing U.S. military presence in Africa — officially at about 6,000 troops, including 300 who trained forces in Cameroon ahead of the 2018 re-election of France’s neoliberal favorite Paul Biya, greenlighting deepened conflict there. However, in 2018 Trump gave free rein to the CIA to expand drone warfare throughout Africa.

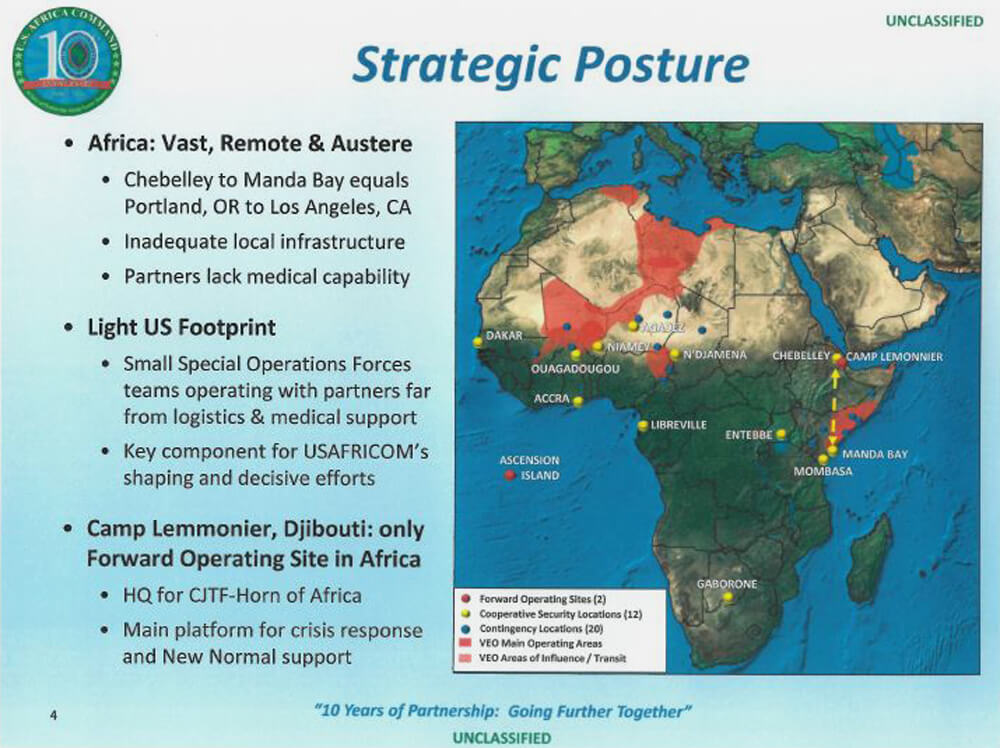

There are at least 34 U.S. military sites in Africa now, including three in Libya, where tensions between rival militias have displaced 3,400 and may soon plunge Tripoli into chaos. The focus of AFRICOM’s presence is largely in oil-rich nations in West Africa and in the Horn of Africa, adjacent to the oil-rich Arab Peninsula.

Like other military expansions undertaken from Washington, there are very clear economic, profit-driven motives for AFRICOM, and those motives serve as the backbone for National Security Advisor John Bolton’s New Africa strategy. While petrodollars are on the mind, the continued ability to exploit African economies is a cornerstone of U.S. financial dominance on the continent.

Africa as the frontline for an arms race between the U.S. and China

Last year at the Heritage Foundation, Bolton said that the West needs to “wake up” to the threat posed by China and Russia in Africa, warning that “China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) toward Africa totaled $6.4 billion dollars” between 2016 and 2017, well above U.S. direct investment, which has continued to slump. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the FDI decline stems from corporate income tax cuts. From 2017, U.S. multinational enterprises have embarked on a large repatriation of accumulated foreign earnings, indicating a growing reluctance to engage in social investment abroad. The speech came months after China’s pledge of $60 billion to Africa in aid and loans.

Djibouti, a focal part of the strategy, is home to the largest known U.S. drone complex in the world, as well as the flagship U.S. base under AFRICOM, Camp Lemonnier, a former French Foreign Legion outpost. The base hosts 4,000 U.S. and allied personnel, and is close to a Chinese Liberation Army Navy base staffed by 400 personnel. The disparities were just enough to gain the ire of the U.S. last year when the Department of Defense accused China of unverified laser attacks on U.S. pilots, used to justify additional U.S. military spending in Africa.

Bolton’s concerns stem from the fact that Djibouti may allow Chinese state-owned enterprises to partially control the Doraleh Container Terminal, a Red Sea shipping port. “Should this occur,” said Bolton:

the balance of power in the Horn of Africa — astride major arteries of maritime trade… — would shift in favor of China, and our U.S. military personnel at Camp Lemonnier could face even further challenges in their efforts to protect the American people.”

How Wall Street is underdeveloping Africa

For an Africa strategy, Bolton’s speech seemed to express more interest in China-in-Africa’s implications for “American national security,” while mentions of the national security of African nation-states were quite sparse — perhaps appropriate, as any mention of the security of African peoples would call into question the arrival of forces from the same country that took enslaved people from the continent mere generations ago.

Bolton did talk of trade though, calling on African countries to practice fiscal responsibility, promote fair and reciprocal trade, deregulate their economies, and support their private sector. He touted negotiations of bilateral trade agreements and the basing of the new Africa strategy in the Marshall Plan, saying how “The Marshall Plan furthered American interests, bypassed the United Nations, and targeted key sectors of foreign economies rather than dissipating aid across hundreds of programs.”

Bolton’s seemingly new strategy mirrors the Clinton Administration’s “trade not aid” doctrine, promoted in the late 1990s. China may have not been a threat to the empire back then, when annual trade of China with Africa totaled only $10 billion in Clinton’s last year in office, while now it stands at $170 billion. Bolton did not give any evidence to prove China’s supposed neocolonial role in Africa, but U.S. objectives are countering China’s “predatory” preference to deal with African governments and work toward local priorities, as contrasted with the U.S. approach of transnational corporate and charity-led programs.

“Prosper Africa” is the Marshall Plan-style approach the administration is taking to reduce aid on top of promoting unregulated capitalism. The potential risks attached to financing infrastructure development will most likely fall on the government rather than the private sector, compromising the transparency of such projects, as seen in the case of Southern Europe. Moreover, there is strong evidence that shows large companies, including multinational corporations and international banks, engage in illicit financial flows from Africa.

In line with Bolton’s priorities, the lack of oversight from the United Nations represents the trend of neoconservative attempts to subvert aspects of the UN system that allow for checks on U.S. power. Zimbabwe, historically known as the “breadbasket of Africa” is set to join the six fastest growing economies in Africa, despite being held back in recent years by U.S. sanctions. The geopolitically rising, albeit economically isolated country voted against U.S. interests 69 times in 2017 and voted in support only six times. On average, African countries vote in line with the U.S. at the UN 31 percent of the time, providing the Trump Administration a clear motive to operate on the continent with as little multilateral accountability as possible.

Bolton’s plans for a new U.S. strategy toward Africa remains vague and largely non-specific. For example, USAID’s GEEL project in Somalia calls for coordination between the national government and the local private sector, but the details of this partnership fostered by USAID are not provided and therefore do not take into account the severe corruption that continues to plague the country. According to Devex, USAID released its first Acquisition and Assistance Strategy, “outlining changes to design and procurement systems promoting innovative methods of collaboration.” However, the page cannot be found. The absence of a transparent and functional financial sector serves as a major obstacle to economic growth in Somalia, especially if there is a de-emphasis on state-led social investment, which Bolton would favor.

While Kenya and Ghana are leading initiatives to promote intra-continental trade, Bolton has been calling for bilateral trade deals between the U.S. and Africa, highlighting the administration’s commitment to its “America First” policy. The U.S. is pushing for the development of an expensive project in Kenya that would cost $3 billion, which the government will likely need large credit facilities to finance. With countering China a main priority, the U.S. will be incentivized to take over debt management, putting in place additional measures, such as demanding the extension of IMF bailouts to African countries on the condition that such financial assistance would not be used to repay China.

Much of U.S. diplomatic effort regarding Libya in recent days follows the spike in oil prices that the civil war there is provoking. While Khalifa Hafter is threatening the current government in Libya, which has been working with Western governments, he is genuinely Europe’s man in Libya — one who intends to guarantee the flow of profits of newly discovered low-sulfur petroleum northward and westward, as opposed to staying in Africa or going to China or Russia, Libya’s long-time allies. As such, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, in a break from his usual modus operandi, is more interested in de-escalating civil tensions in Libya, hoping to get in on the spoils.

Peace by pacification

Under the pretext of fighting Al-Shabab, the resurgence of airstrike diplomacy doesn’t skip a beat as U.S. policy, even when the leadership of the people we victimize comes to Washington. Said Bolton:

Under our new strategy, we will also take additional steps to help our Africans fight terrorism and strengthen the rule of law. We will assist key African governments in building the capacity of partner forces and security institutions to provide effective and sustainable security and law enforcement to their citizens.”

The U.S. drone war in Africa has hit southern Somalia particularly hard. With General Thomas Waldhauser admitting the U.S. killed 14 Somali civilians last month in five airstrikes, anti-American sentiment is mounting on top of an already existing Somali public debate critical of U.S. policy. It follows last year’s deadly U.S. assaults, accompanied by AFRICOM-backed Somali forces, on Somali rural workers in Afgooye, killing people the Pentagon alleged were Al-Shabaab militants. After U.S. attacks on Somali people, many local leaders now anticipate how stories will spun to paint victims as terrorists.

U.S. policy in Africa intends to put more effort into Vietnamization-style operations in Niger, Mali, Libya, and Somalia and, since the French invasion of Mali in 2012, the U.S. has tried to exert its influence within the G5 Sahel Force (with the intent of adding 5,000 troops — Bolton’s favorite number) of which Mali is a key member. Mali’s northern oil reserves — bordering fellow G5 countries, such as Mauritania — are being pursued by oil interests among businesses in Australia, France, and Qatar.

The Trump Administration is justifying an expansion in U.S. military presence in these African countries as a means of securing an environment that would be stable enough to clear the way for economic pursuits — mainly for U.S. businesses to take advantage of Africa’s light industry, while profiting from mineral wealth across the continent. As such, it is perhaps no surprise there is very little public support within these countries for U.S. military intervention.

Top photo | A member of the U.S. Army Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa communications directorate speaks with Djibouti Army soldiers at FAD Headquarters, Djibouti, Dec. 26, 2018. U.S. Air Force | Shawn Nickel