Trump promised to rein in drug prices. It was his only sensible campaign promise.

But the plan he announced Friday does little but add another battering ram to his ongoing economic war against America’s allies.

He calls it “American patients first,” and takes aim at what he calls “foreign freeloading.” The plan will pressure foreign countries to relax their drug price controls.

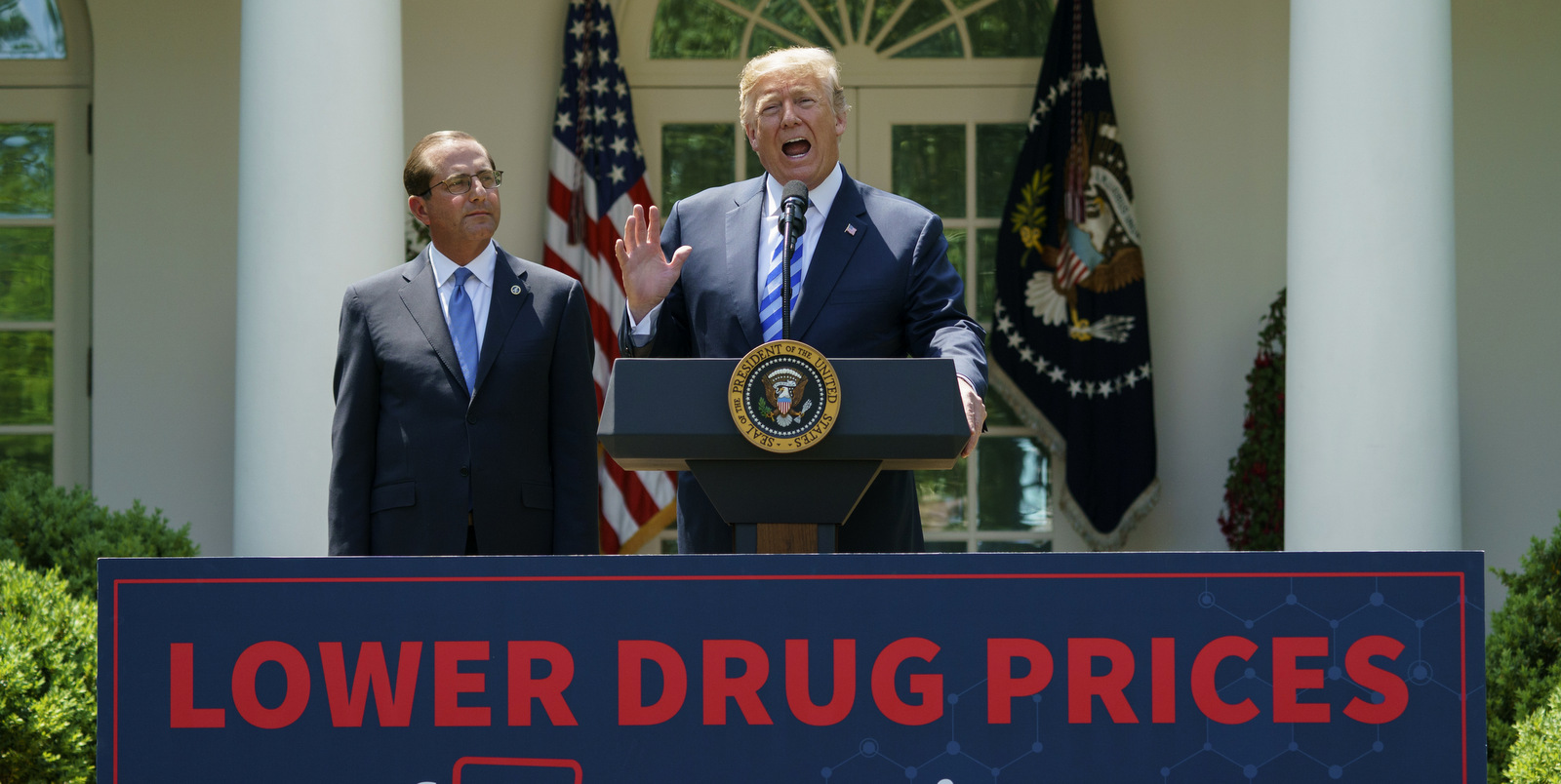

America’s trading partners “need to pay more because they’re using socialist price controls, market access controls, to get unfair pricing,” said Alex Azar, Trump’s Secretary of Health and Human Services, who, perhaps not incidentally, was a former top executive at the drug maker Eli Lilly and Company.

By this tortured logic, if other nations allow drug companies to charge whatever they want, U.S. drug companies will then lower prices in the United States.

This is nonsensical. It would just mean more profits for U.S. drug companies. (Revealingly, the stock prices of U.S. pharmaceutical companies rose after Trump announced his plan.)

While it’s true that Americans spend far more on medications per person than do citizens in any other rich country – even though Americans are no healthier – that’s not because other nations freeload on American drug companies’ research.

Big Pharma in America spends more on advertising and marketing than it does on research – often tens of millions to promote a single drug.

The U.S. government supplies much of the research Big Pharma relies on through the National Institutes of Health. This is a form of corporate welfare that no other industry receives.

American drug companies also spend hundreds of millions lobbying the government. Last year alone, their lobbying tab came to $171.5 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

That’s more than oil and gas, insurance, or any other American industry. It’s more than the formidable lobbying expenditures of America’s military contractors. Big Pharma spends tens of millions more on campaign expenditures.

They spend so much on politics in order to avoid price controls, as exist in most other nations, and other government attempts to constrain their formidable profits.

For example, in 2003, Big Pharma got a U.S. law prohibiting the government from using its considerable bargaining clout under Medicare and Medicaid to negotiate lower drug prices. Other nations with big healthcare plans routinely negotiate lower drug prices.

During his campaign Trump promised to reverse this law. But the plan he revealed Friday doesn’t touch it. Trump’s plan seeks only to make it easier for private health insurers to negotiate better deals for Medicare beneficiaries.

In reality, private health insurers don’t have anywhere near the clout of Medicare and Medicaid – which was the whole point of Big Pharma’s getting Congress to ban such negotiations in the first place.

In the last few years, U.S. drug companies have also blocked Americans from getting low-cost prescription drug from Canada, using the absurd argument that Americans can’t rely on the safety of drugs coming from our northern neighbor – whose standards are at least as high as ours.

Trump’s new plan doesn’t change this, either.

To put all this another way, when Americans buy drugs in the United States, they really buy a package of advertising, marketing, and political influence-peddling. Consumers in other nations don’t pay these costs. Which explains a big part of why drug prices are lower abroad. Trump’s so-called plan to lower drug prices disregards this reality.

Trump’s plan nibbles at the monopoly power of U.S. pharmaceutical companies, but doesn’t deal with the central fact that their patents are supposed to run only twenty years but they’ve developed a host of strategies to keep patents going beyond then.

One is to make often insignificant changes in their patented drugs that are enough to trigger new patents and thereby prevent pharmacists from substituting cheaper generic versions.

Before its patent expired on Namenda, its widely used drug to treat Alzheimer’s, Forest Labs announced it would stop selling the existing tablet form of in favor of new extended-release capsules called Namenda XR. Even though Namenda XR was just a reformulated version of the tablet, the introduction prevented generic versions from being introduced.

Other nations don’t allow drug patents to be extended on such flimsy grounds. Trump’s plan doesn’t touch this ploy.

Another tactic used by U.S. drug companies has been to sue generics to prevent them from selling their cheaper versions, then settle the cases by paying the generics to delay introducing those cheaper versions.

Such “pay-for-delay” agreements are illegal in other nations, but antitrust enforcement hasn’t laid a finger on them in America – and Trump doesn’t mention them although they cost Americans an estimated $3.5 billiona year.

Even after their patents have expired, U.S. drug companies continue to aggressively advertise their brands so patients will ask their doctors for them instead of the generic versions. Many doctors comply.

Other nations don’t allow direct advertising of prescription drugs – another reason why prices are lower there and higher here. Trump’s plan is silent on this, too. (Trump suggests drug advertisers should be required to post the prices of their drugs, which they’re already expert at obscuring.)

If Trump were serious about lowering drug prices he’d have to take on the U.S. drug manufacturers.

But Trump doesn’t want to take on Big Pharma. As has been typical for him, rather than confronting the moneyed interests in America he chooses mainly to blame foreigners.

Top Photo | President Donald Trump speaks during an event about prescription drug prices with Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar in the Rose Garden of the White House in Washington, Friday, May 11, 2018. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Robert Reich is the nation’s 22nd Secretary of Labor and a professor at the University of California at Berkeley. Reich’s documentary, “Saving Capitalism,” is streaming on Netflix. His latest book, “The Common Good,” is available in bookstores now.

This article was made possible by the readers and supporters of AlterNet, where it first appeared.