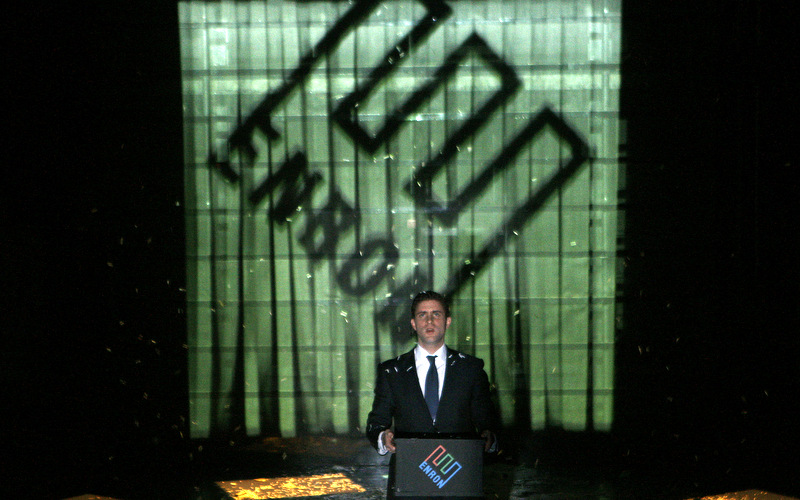

WASHINGTON — Invoking the scandal that led to the collapse of Enron, the U.S. Supreme Court has declared that employees of private companies that contract with public corporations are entitled to the same whistleblower protections as the employees of the public entities themselves.

In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court granted two former employees the ability to sue the mutual fund advisory company they worked for following their dismissal after they brought attention to accounting issues.

“The decision is a big win for corporate whistleblowers,” said Rebecca Hamburg Cappy of the Alliance for Justice and previously of the National Employment Lawyers Association, for which she wrote an amicus brief.

It will also “benefit the millions of Americans who invest in mutual funds because, in the mutual fund industry, it’s these private corporate entities that file the reports to the SEC,” Cappy told MintPress News.

The legacy of Enron

From 1995 to 2000, Fortune Magazine called Enron Corporation the most innovative company in the country. Well-regarded financial analysts from Goldman Sachs and other investment banking firms used a number of glorious adjectives like “extraordinary” to describe the corporation. Yet, in 2001, Sherron Williams sent Enron Chairman Kenneth Lay a memo alerting him to financial irregularities.

Williams, the vice president of the company at the time, told Lay that she was concerned the company “will implode in a wave of accounting scandals.”

“We are under too much scrutiny and there are probably one or two disgruntled ‘redeployed’ employees who know enough about the ‘funny’ accounting to get us in trouble,” she wrote.

By the end of the year, the company with 20,000 employees filed for bankruptcy. Enron’s revenues the previous year had exceeded $100 billion, thanks to its electricity, natural gas, communications and paper businesses.

Watkins’ concerns proved right: An anonymous employee provided a tip to the Internal Revenue Service about such “funny accounting,” which had allowed Enron to evade taxes on more than $600 million in income by using illegal tax shelters while also reporting more than $300 million in bogus profits to boost company stock prices lining the pockets of the likes of Lay, who died while on trial, and Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling, who is currently serving time for conspiracy, securities fraud and insider trading.

Congressional action

Looking to protect investors and employees from “future Enrons,” Congress moved quickly to pass the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act, commonly known as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. Among other provisions, Sarbanes-Oxley offered legal protections to employees of public companies with information of corporate wrongdoing as a way of motivating them to reveal such information to the public. Whistleblowers were to be protected from retaliation, including “discharge, demotion, suspension, threats, harassment or discrimination.”

Last week’s Supreme Court ruling expanded those protections to include employees of private companies who contract with public companies such as accounting firms and law firms and have access to their financial records.

In 2007, Jackie Hosang Lawson and Jonathan Zang both worked for management companies — now collectively FMR LLC — that helped oversee mutual funds organized by Fidelity Investments. They independently brought complaints to their employers about issues regarding how the mutual funds were managed, and both faced repercussions for their actions. Zang was terminated, while Lawson claimed that she was passed over for a promotion and threatened with punishment for insubordination.

Both filed charges with the Labor Department’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration which handles whistleblower regulation enforcement, and both filed lawsuits against FMR. The company responded that Lawson and Zang were not entitled to protection, however, because they were not employees of the mutual funds.

Mutual danger funds

Mutual funds typically have no employees. Instead, they rely on companies to advise the boards that direct them as well as handle SEC filings.

In 2011, David F. Swensen, chief investment officer at Yale University and the author of “Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment,” wrote in The New York Times that mutual fund management “employed market volatility to produce profits for itself far more reliably than it has produced returns for its investors.”

“Too often, investors believe that mutual funds provide a safe haven, placing a misguided trust in brokers, advisers and fund managers,” he continued. “The companies that manage for-profit mutual funds face a fundamental conflict between producing profits for their owners and generating superior returns for their investors.”

Without their own employees and with the employees of the advising company lacking protection, there would not be anyone to bring attention to faulty accounting or filings.

Business reaction

The 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decided in favor of FMR, finding that, through Sarbanes-Oxley, Congress only sought to protect employees of public companies, not employees of private ones, a position put forth by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

The Chamber of Commerce’s National Chamber Litigation Center declined to comment, but in a brief previously filed with the Supreme Court, the chamber argued that “extending SOX to reach those employees would not advance [Sarbanes-Oxley’s] investor-protection goals and would be directly contrary to Congress’s objective of protecting small businesses from the costs and burdens of SOX coverage.”

“We are really concerned about what this decision will mean for smaller companies that must work with larger public companies,” said Karen Harned, executive director of the National Federation of Independent Business Small Business Legal Center. “This is going to require them to go through all of these requirements to protect themselves and it will mean more litigation in the end.”

However, Eric Schnapper, a professor at the University of Washington School of Law who represented Lawson and Zang before the Supreme Court, argued that the decision actually works in the long-term interest of the public entities such as the mutual funds Sarbanes-Oxley was designed to protect.

“Anybody who works for any company that discovers some kind of fraud can go to the FBI and they’re protected,” Schnapper said. “Up until now, if someone were to go a lawyer and ask if it was safe to complain, the lawyer would say, ‘Don’t tell the employer — they can fire you.’ Would they really prefer these employees go to the FBI before telling their employers?”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, writing for the majority, agreed with Schnapper.

“The legislative record shows Congress’ understanding that outside professionals bear significant responsibility for reporting fraud by the public companies with whom they contract, and that fear of retaliation was the primary deterrent to such reporting by the employees of Enron’s contractors,” Ginsburg wrote. “Sarbanes-Oxley contains numerous provisions designed to control the conduct of accountants, auditors, and lawyers who work with public companies….”

Cappy, of the Alliance for Justice, stressed that private contractors — such as accounting firm Arthur Andersen LLC — were involved in the Enron scandal by helping Enron managers to cover up fraud. At the time, there was no incentive for employees of Arthur Andersen or other firms working with Enron to blow the whistle. If they were to do so, they were likely lose their jobs and damage their reputation in the industry.

“That’s what Congress intended when they passed Sarbanes-Oxley after Enron,” Cappy said.

“But must it be such a broad brush?” asked Harned of the Small Business Legal Center. “There’s no line here, so the concern is that in this litigious society, we’re worried it will shoehorn small business owners because they won’t get that big contract unless they comply with the Sarbanes-Oxley regime, which will affect their ability to expand their business.”

Schnapper dismissed the concerns, saying, in practice, it really only impacts mutual funds and accounting firms.

“It’s very important for mutual funds and accounting firms and, in some sense, lawyers,” Schnapper explained. “They’re the ones that would know about the SEC filings and would see anything improper.”