As the rich get ever richer — courtesy, in countries like the United States, of corporate-friendly deregulation and tax “reform” — does the planet get ever warmer and dirtier? New research suggests economic balance is linked to environmentally-friendly practices. Countries with lower rates of economic disparity have citizens who enjoy a better quality of life and leave a significantly smaller carbon footprint.

By resisting plutocracy and pushing towards an equal wealth distribution throughout the world, the global population can collectively reduce its carbon footprint and combat global climate change head-on.

Measuring income inequality and environmental impacts

In his new book, The Equality Effect, Danny Dorling analyzes the correlation between income inequality and environmental impact in the wealthiest 25 countries in the world. To do this, he developed a comparison ratio between the wealthiest 10 percent of households and the poorest 10 percent of households. Next, he ranked the countries based on their wealth disparity ratio and evaluated their environmental practices.

According to the New Internationalist, Dorling used 11 different environmental metrics — including such categories as waste removal and transportation — to establish a benchmark for comparison. He then created graphs to show the relationship between each country’s wealth disparity and its environmental practices.

Dorling found that the United States has the highest levels of income disparity. The income disparity ratio of the best-off tenth of households to the worst-off tenth in the U.S. is a factor of 20.3 That is, the richest tenth have incomes on average over 20 times that of the poorest tenth. This makes the U.S. the most substantially unequal of the world’s richest countries. It is followed by Singapore with a ratio of 18.5 and Israel at 17.4. The wealthiest countries with the lowest rates of income disparity include Belgium at 5.9, Slovenia at 5.5, and Denmark at 5.2.

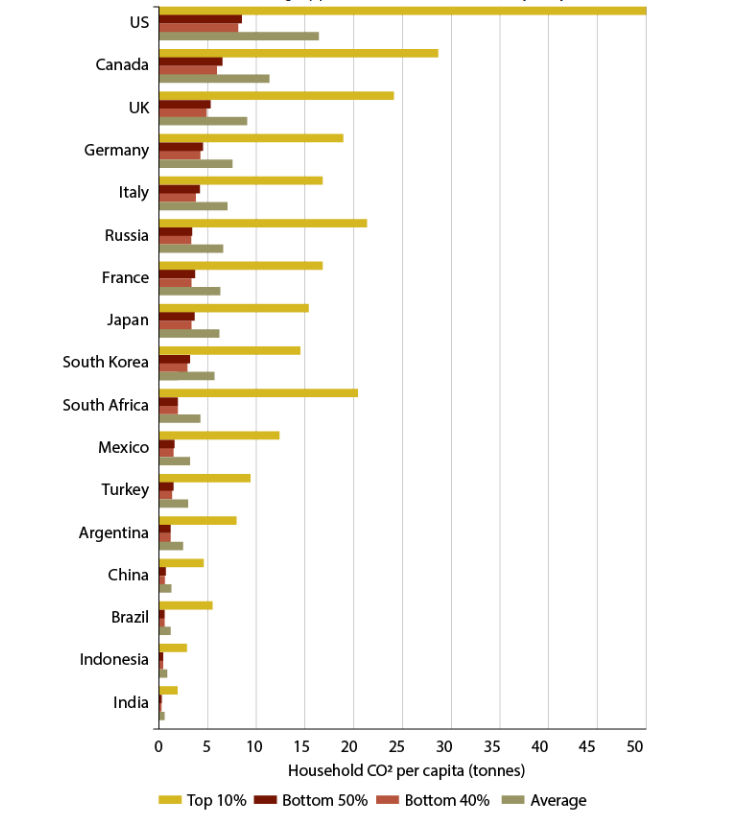

Examining, to take one example, the environmental metric of waste production, Dorling found that the United States produces nearly twice the amount of waste per person as Japan, and almost three times the amount of waste as France. More generally, approximately 49 percent of the waste generated by the wealthiest 25 countries is created by the richest 10 percent of the population, while the poorest 50 percent account for only 10 percent of the waste production.

Ultimately, Dorling found a direct correlation showing the countries with the highest levels of income inequality also have the highest negative environmental impact. The New Internationalist does note data accuracy may vary based on how honestly individuals reported their income, which may slightly alter the results shown. Data trends also show several outliers, which may be due to differences in record keeping and data tracking of environmental practices.

Income disparities and a culture of waste

Citizens in countries with high levels of income inequality face a significant amount of pressure to outperform their peers. This pressure typically comes in the form of an acquisition imperative. Neighbors work harder to acquire more wealth, which, in turn, is used to purchase better, more expensive items such as larger homes, larger vehicles and more personal goods. This pressure is also applied to the acquisition of property and the construction of houses.

The emphasis on acquiring the most advanced or newest items creates a culture of waste. Rather than purchase used items from a consignment shop or hold onto products that still have a generous life expectancy, the temptation and practice is to dispose of these things and replace them with newer models. Older products are occasionally donated, but they are primarily disposed of in landfills or waste-to-energy facilities.

Basic steps that could be taken

To remedy this issue, countries need to shift their mindset. Rather than focusing on acquiring more, newer and better products, they could instead focus on using what they already have and purchase used items instead of investing in new ones. Also, consumers could scale back their purchases to focus on what they need rather than what they want — or need only for the purpose of competing with their neighbors.

Ultimately, this would lead to a reduction in the volume of resources used to produce newer products, which in turn would leave more resources intact for future generations. The amount of material placed in landfills would also be reduced, as more products would be used for the full duration of their life cycles instead of being disposed of early.

Higher rates of consumption are also linked to higher rates of greenhouse gas emissions. Wealthy residents are more likely to have larger homes that require more heat and electricity. They also have more disposable income to invest in costly, inefficient vehicles that have higher rates of emissions and need more fossil fuels to operate.

Countries with lower rates of wealth inequality also have a more substantial portion of their population using public transportation. Public transportation is more economical than paying for parking in downtown areas, and it also uses less energy per capita when compared to driving individual vehicles. Improving public transit in countries with higher rates of income disparity could foster greater interest in using such transportation, which in turn would reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Wealthier countries with a larger economic differential also tend to have larger meat-eating populations. Cattle and other domestic livestock are an inefficient form of food. Farmers grow large volumes of crops which are then fed to cattle and stock. The cattle and stock are then butchered and eaten by humans. The entire process is more water-, food-, waste-, and labor-intensive than eating crops in place of meat. Meat is also transported vast distances, which increases the global carbon footprint.

Humans can reduce their carbon footprint now by reducing their meat consumption. The reduction in demand for meat products will lead to a decrease in production, which will decrease the overall volume of methane gas produced by cattle and the carbon emissions from transporting meat over long distances. Instances of obesity may be reduced as well because excessive meat consumption has been linked to excess weight gain.

The U.S. in retrograde

The United States, the country with the highest economic disparity, is especially struggling to cope with issues of economic equality and environmental justice, both of which are under legislative and executive assault. During the first year of his term, President Donald Trump appointed multiple individuals with strong ties to the fossil fuel industry to positions within the environmental and energy sector — ties that seem destined to influence their decisions regarding environmental legislation.

For example, newly appointed EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt aims to eliminate the Clean Power Plan, a regulation designed to reduce carbon emissions produced by the U.S.’s power industry. Pruitt claimed the regulation spurred a “war on coal” and hopes that by removing the regulation, he will be able to promote more coal usage in the United States. If Pruitt succeeds in repealing this regulation, the greenhouse gas emissions produced by the coal industry will likely increase.

Trump has also proposed a new tax bill that will eventually create yet more income inequality throughout the United States. Corporations will have their tax rate reduced from 35 percent to 20 percent, while lower-income Americans may see higher tax rates over time. Additionally, popular deductions that benefit individuals at lower income brackets will be removed. The administration claims the tax reforms will benefit all citizens, though projections show this is almost certainly not the case — and there is little argument that the lion’s share of the benefits will not accrue to the already wealthy, thereby further exacerbating the wealth and income gaps.

Countries with lower rates of wealth disparity tend to have happier citizens and offer a better quality of life. A more nearly equal distribution of wealth is also shown to have substantial environmental benefits as less meat is consumed, less waste is produced, and citizens consume what they need rather than acquiring excess products.

Individuals in all nations can begin to make a difference now by taking public transportation, reusing products, and avoiding the gratuitous purchase of items they don’t need.

Granted, a consumer-driven country like the U.S. is unlikely to be able to break apart from the mass purchase of unnecessary items — it’s what fuels the very fabric of the U.S. economy.

Most advertising appears specifically designed to make buyers feel comparatively and competitively inadequate, in order to drive them to purchase the supposed “cures” for those inadequacies.

It’s an unfortunate truth, and the U.S. likely won’t see a massive shift toward healthier consumption habits anytime soon. However, everyone can do their own part as individuals to be more conscious and reflective about the way they live and the luxuries they already have — such mindful actions can have more of an impact than one might guess.

Top photo | Holiday shoppers scramble to get deals at Walmart on the day before Black Friday, Nov. 23, 2017 in Bentonville, Ark. (Gunnar Rathbun/AP)

Kate Harveston is a political journalist with an interest in human rights issues, foreign policy, and social change. You can read her work at MintPress News or on her blog, onlyslightlybiased.com.