The journey from Sana’a to the far northeastern stretches of al-Jawf through the Empty Quarter is an arduous affair. A veritable no man’s land, the region has long-enjoyed the dubious distinction of hosting strongholds of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), a group that evolved and blossomed under the sponsorship of nearby Saudi Arabia. The journey crisscrosses what seems like endless valleys of identical dunes with little more than the blazing sun to provide a semblance of direction.

In perfect weather under the flecks of golden sunshine that mingled with the few clouds in the early morning sky, we set off northeast from the capital Sana’a, passing through the Nihm district, the gateway to al-Jawf. After crossing the Fardhah Nihm checkpoint, dozens of burned-out armored vehicles of American and Canadian origin could be seen on both sides of the road.

Life is gradually returning to the area’s villages and shops and restaurants have opened their doors again.

In January 2020, Yemen’s Houthi-allied army, supported by local tribes, launched a retaliatory military operation to recapture Nihm from Saudi Coalition forces. Nihm lies east of Yemen’s capital city of Sana’a, one of the most strategically important battlefields in Yemen. Two thousand Saudi fighters, including members of al-Qaeda, ISIS, and other armed groups under the patronage of the Saudi Monarchy, met their end or were captured in the operation. By March, the Yemeni army had successfully subdued Nihm and advanced all the way to al-Jawf and Marib. Now, for the first time in nearly 55 years, al-Jawf and most of Marib Province is under Yemeni control following decades of de facto rule by Riyadh through its various Yemeni proxies.

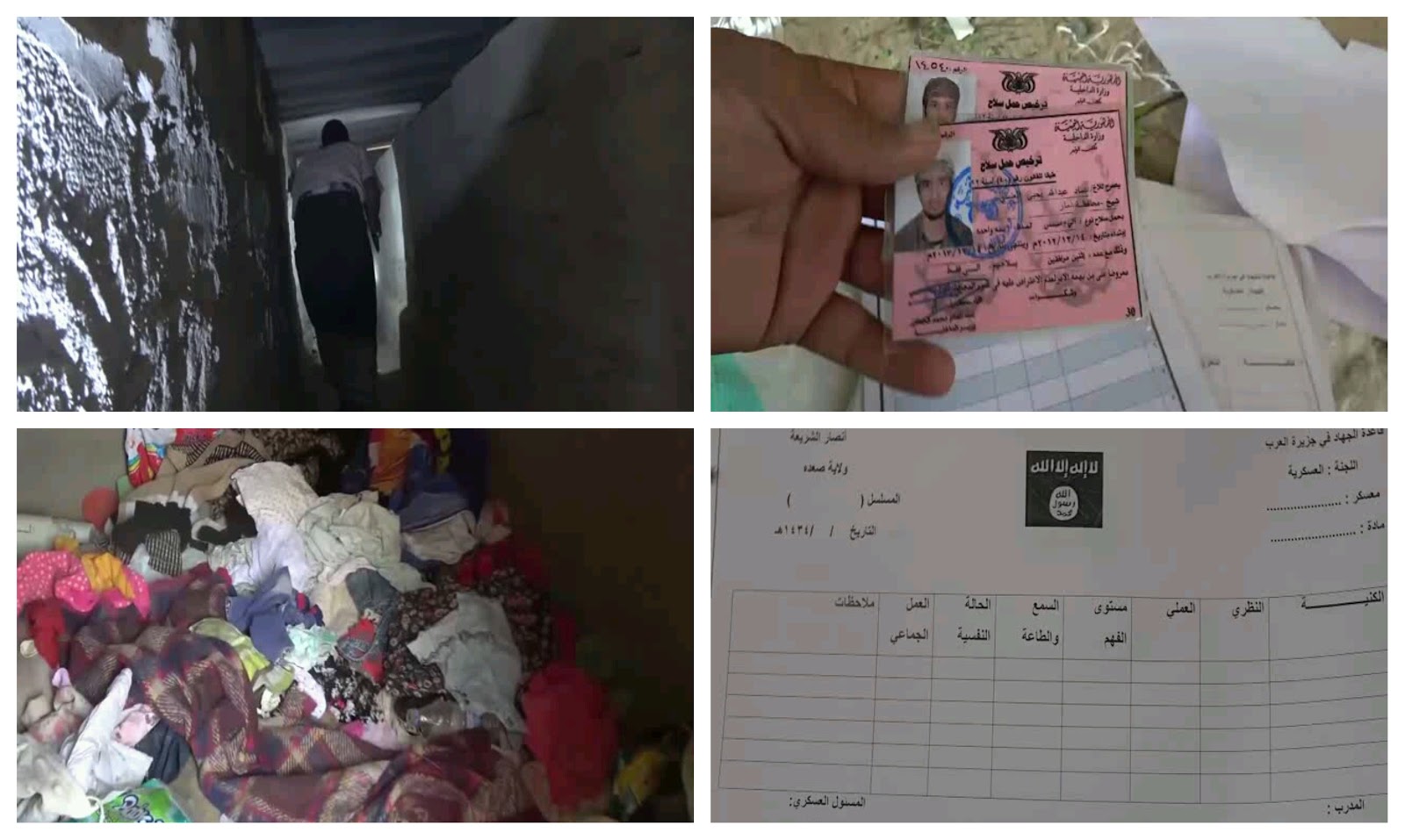

In their haste to escape the coming onslaught, Saudi forces left behind a slew of both medium and heavy weapons as well as the ammunition required to make them come to life. Whole stores of weapons, unexploded ordnance, and mines were abandoned, often amidst the tattered flags of Saudi Arabia and al-Qaeda and in huge tunnels reminiscent of those left behind in the wake of the wars in Syria and Iraq. It wasn’t just weapons that were left behind, the scent of corpses still lingers in the region’s reefs, valleys and rugged mountains.

The residents of Nihm’s sleepy desert towns are beginning to return to their villages. A wary feeling of safety and relative stability accompanies the slow trickle of life as it returns, interrupted by everpresent reminders that the war is far from over, reminders that come in the form of the wild dogs feeding on abandoned corpses, Saudi warplanes that make the occasional visit, and most acutely, a significant number of unexploded ordnances, the remnants of cluster bombs and other munitions still embedded in the ground. Those, according to Adel, a grocery store owner in the roadside village of Khalgah in Nihm, pose the most immediate danger.

Nihm, like most cities in Yemen, has been hit by a barrage of indiscriminate airstrikes, over 250,000 since 2015 when the war began. According to the Yemeni Army, 70 percent of those airstrikes have hit civilian targets. Thousands of tons of weapons, most often supplied by the United States, have been dropped on hospitals, schools, markets, mosques, farms, factories, bridges, and power and water treatment plants and have left unexploded ordnances scattered across densely populated areas.

A kidnapping in al-Hazm

After a six-hour drive beneath the watchful eye of the Coalition warplanes that seemed to be constantly buzzing overhead, we were met with horrific scenes in al-Hazm. A simple desert city notorious for its connections to Al-Qaeda, al-Hazm is one of the largest cities in al-Jawf and was home to some of the fiercest fighting in the battle to route Coalition ground fighters. The effects of airstrikes in the city appeared everywhere; digging into the asphalt roads, destroying homes, schools and government complexes. Smoke was still lingering from an airstrike that hit less than a kilometer away from us as we arrived.

It was in al-Hazm that a broken-hearted mother told us of how she allowed herself a renewed sense of hope that the defeat of the Coalition would lead to information about her loved ones. “Two years have passed since they kidnapped my daughter,” she told MintPress, a black niqab covering her face and tears flowing as she recounted one of the worst crimes carried out by the Saudi coalition in al-Jawf. In a case that managed to gain local notoriety for its sheer brutality, her daughter, Samirah Hezam Maharesh, a mother of three young girls, was kidnapped from her home in al-Hazam on July 5, 2018, by armed militants loyal to Saudi Arabia.

First, Samirah was taken to a secret prison in the provincial capital and then transferred to another prison. Her whereabouts are still unknown and the only tidbits of hope come from unconfirmed local news stories and occasional rumors.

The kidnapping of Samirah crossed a red line in Yemen’s conservative society, which is heavily steeped in tribal tradition, and sparked dozens of demonstrations throughout the country’s northern provinces. In addition to other atrocities carried out by AQAP, the kidnapping ultimately helped push local residents to risk it all and join the resistance led by the Houthis against the Saudi Coalition and its militant allies.

Residents told us that Samirah was just one of the hundreds of Yemenis who were snatched from their homes or cars at checkpoints in al-Jawf and Marib. During their reign in al-Jawf, Saudi-backed militants, including al-Qaeda, committed horrendous abuses against those it saw as an obstacle to their occupation.

An unholy union

Since 2015, when Saudi Arabia announced from Washington D.C. that it had launched a military campaign against the poorest country in the Middle East, it has been an open secret that both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates had formed an unholy union with al-Qaeda’s branch in Saudi Arabia and Yemen, known colloquially as AQAP, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

In al-Jawf, the relationship between Saudi Arabia and AQAP was well underway by 2016 when the Kingdom launched a military campaign to take the province. Saudi and AQAP forces fought side by side, sharing the same weapons, trenches, operations command centers, resting places, and extremist ideals. The only thing they didn’t share was a desire to destroy the United States, a trait exclusive to al-Qaeda according to documents left behind by fallen fighters and the confessions of Saudi soldiers captured in the battle for al-Jawf.

AQAP has hobbled by in Yemen for years, feeding off the relentless cycle of poverty and hunger and only occasionally emerging from the shadows to claim credit for an attack or seek new recruits. It was not until 2015 when the group began to receive support from Saudi Arabia that it become brazen enough to emerge from its hiding places into the streets of al-Jawf’s towns. Generous Saudi backing meant that AQAP could boost recruitment, build new training camps and promote the organization’s ideology, an offshoot of the official Saudi state religion of Wahhabism. By early 2020, AQAP had a sizable real estate portfolio in al-Jawf and Marib and ran most of the provinces’ large businesses. Sprawling villages in al-Jawf, the second largest governorate in Yemen, turned into strongholds of the organization after residents were forced to flee to other areas. AQAP turned some of the abandoned homes into factories used to manufacture explosive belts, IEDs and car bombs. Others were used to stock weapons, train fighters and prepare for their “global Jihad.”

The secret prison’s of Khazaf and al-Marwan

Finally, we reached two of al-Qaeda’s main strongholds in the far northeastern Khab and al-Shaf districts, near the edge of the expansive Rub’ al Khali Desert (the Empty Quarter). The villages of Khazaf and al-Marwan are little more than dried up oases scattered in the remote desert like the remains of some ancient colony. It was here that humble houses made from dried mud bricks were turned into factories, secret prisons, and centers for the dissemination of extremist Wahhabi propaganda.

Villagers here described bottle dungeons dug into the dirt floors of local houses. Accessible only via small overhead hatches, they were used by militants to keep prisoners, including captured female slaves, as well as dead bodies. Deep below two houses, we were shown complex tunnels systems ostensibly used to hold and torture prisoners. The stench of human death lingered in the dark tunnels mingling with the smell of dust and concrete. The tunnels were also used as corridors to move weapons and supplies from house to house undetected.

Inside one home that turned it into a makeshift AQAP prison, we saw four three-square-meter windowless cells with heavy steel doors. As we made our way from cell to cell, I was struck by the sight of a pile of woman’s clothing, a prayer outfit, and a baby’s diapers, all piled into a morbid testament of the crimes committed here. I also found a note, a scrap of paper with the following scribbled onto it: ” I am Um Assamah, Why did you imprison me and my three daughters?” Samira is rumored to have been held in these same cells.

Residents who participated in the fight against the Saudi-backed militants told us that the place was a women’s prison that “from outside it looked like simple houses but when we entered, we found cells, tunnels, and implements of torture,” a 60-year-old man with a white beard recounted, barely holding back his tears and gripping the rifle slung over his shoulder. In Yemen, a woman’s incarceration is considered a great disgrace.

Other homes in Khazaf were used to make booby traps and explosives. In a small meeting room adorned with AQAP flags, 12 bags of high-explosive TNT lay piled against a wall. A hundred meters away, another home was turned into a makeshift workshop to produce vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices. In the yard, a 1984 Toyota Land Cruiser lay abandoned, laden with a barrel of TNT in its last stages of preparation. The truck was most likely intended to be used against large gatherings according to local resistance fighters.

An attempt to coverup war crimes

There is little doubt that untold war crimes occurred in the forgotten desert villages and in a brazen effort to conceal their involvement, Saudi warplanes hit them hard last week. Khazaf and al-Marwan were pounded by barrages of Coalition airstrikes, it appears, however, that their hail mary may have come too late. Video filmed by local fighters and shared MintPress as well as with Houthi media document many of the crimes that took place as well as the forces behind them.

Local fighters told us that they weren’t even aware of the existence of some of the bunkers, laboratories and tunnels until after they were exposed beneath the rubble of the Saudi airstrikes which targeted specific homes.

Now, in a last-ditch effort to revive what’s left of their AQAP allies in al-Jawf, Saudi Arabia has renewed its battlefield campaign in the province of al-Bayda after over a year of relative quiet there. Al-Bayda lies close to Marib, where some of the most extremist militants allied with the Coalition reside. Backed by Saudi warplanes, AQAP carried out two operations in Nate’a and Qaniyah on Wednesday, lasting over 10 hours according to the Yemeni army.

Feature photo | Saudi-allied militants ride on the back of a pick-up truck in an area between Yemen’s northern provinces of al-Jawf and Marib, December 5, 2015. Ali Owidha | Reuters

Ahmed AbdulKareem is a Yemeni journalist. He covers the war in Yemen for MintPress News as well as local Yemeni media.