LONDON — In a previous investigation, MintPress News explored how one university department, the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, functions as a school for spooks. Its teaching posts are filled with current or former NATO officials, army officers and intelligence operatives to churn out the next generation of spies and intelligence officers. However, we can now reveal an even more troubling product the department produces: journalists. An inordinate number of the world’s most influential reporters, producers and presenters, representing many of the most well-known and respected outlets — including The New York Times, CNN and the BBC — learned their craft in the classrooms of this London department, raising serious questions about the links between the fourth estate and the national security state.

National security school

Increasingly, it appears, intelligence agencies the world over are beginning to appreciate agents with a strong academic background. A 2009 study published by the CIA described how beneficial it is to “use universities as a means of intelligence training,” writing that, “exposure to an academic environment, such as the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, can add several elements that may be harder to provide within the government system.”

The paper, written by two King’s College staffers, boasted that the department’s faculty has “extensive and well-rounded intelligence experience.” This was no exaggeration. Current Department of War Studies educators include the former Secretary General of NATO, former U.K. Minister of Defense, and military officers from the U.K, U.S. and other NATO countries. “I deeply appreciate the work that you do to train and to educate our future national security leaders, many of whom are in this audience,” said then-U.S. Secretary of Defense (and former CIA Director) Leon Panetta in a speech at the department in 2013.

King’s College London also admits to having a number of ongoing contracts with the British state, including with the Ministry of Defence (MoD), but refuses to divulge the details of those agreements.

American connections

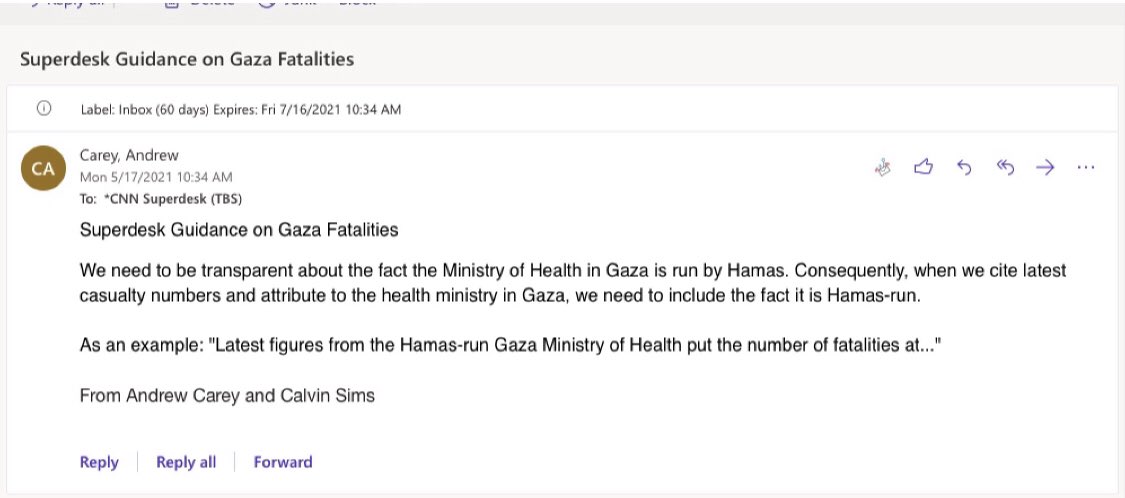

Although a British university, King’s College markets itself heavily to American students. There are currently 1,265 Americans enrolled, making up about 4% of the student body. Many graduates of the Department of War Studies go on to attain powerful positions in major American media outlets. Andrew Carey, CNN’s Bureau Chief in Jerusalem, for example, completed a master’s there in 2012. Carey’s coverage of the latest Israeli attack on Gaza has presented the apartheid state as “responding” to Hamas rocket attacks, rather than being the instigator of violence. A leaked internal memo Carey sent to his staff last month at the height of the bombardment instructed them to always include the fact that the Gazan Ministry of Health is overseen by Hamas, lest readers begin to believe the well-documented Palestinian casualty figures brought on by days of bombing. “We need to be transparent about the fact that the Ministry of Health in Gaza is run by Hamas. Consequently, when we cite latest casualty numbers and attribute to the health ministry in Gaza, we need to include the fact that it is Hamas run,” read his instructions.

Once publicized, his comments elicited considerable pushback. “This is a page straight out of Israel’s playbook. It serves to justify the attack on civilians and medical facilities,” commented Al-Jazeera Senior Presenter and Producer Dena Takruri.

The New York Times, the United States’ most influential newspaper, has also employed Department of War Studies alumni. Christiaan Triebert (M.A., 2016), for example, is a journalist on their visual investigations team. He even won a Pulitzer Prize for “Revelations about Russia and Vladimir Putin’s aggressive actions in countries including Syria and Europe.” Hiring students from the school for spooks to bash Russia appears to be a common Times tactic, as it also employed Lincoln Pigman between 2016 and 2018 at its Moscow bureau.

Josh Smith, senior correspondent for influential news agency Reuters and formerly its correspondent in Afghanistan, also graduated from the department in question, as did The Wall Street Journal’s Daniel Ford.

Arguably the most influential media figure from the university, however, is Ruaridh Arrow. Arrow was a producer at many of the U.K.’s largest news channels, including Channel 4, Sky News and the BBC, where he was world duty editor and senior producer on Newsnight, the network’s flagship political show. In 2019, Arrow left the BBC to become an executive producer at NBC News.

The British invasion

Unsurprisingly for a university based in London, the primary journalistic destination for Department of War Studies graduates is the United Kingdom. Indeed, the BBC, the country’s powerful state broadcaster, is full of War Studies alumni. Arif Ansari, head of news at the BBC Asian Network, completed a masters analyzing the Syrian Civil War in 2017 and was soon selected for a leadership development scheme, placing him in charge of a team of 25 journalists who curate news primarily geared toward the substantial Middle Eastern and South Asian communities in Great Britain.

Many BBC employees begin studying at King’s years after their careers have already taken off, and balance their professional lives with pursuing new qualifications. Ahmed Zaki, Senior Broadcast Journalist at BBC Global News, began his master’s six years after he started at the BBC. Meanwhile, Ian MacWilliam — who spent ten years at BBC World Service, the country’s official news broadcast worldwide, specializing in sensitive regions like Russia, Afghanistan and Central Asia — decided to study at King’s more than 30 years after completing his first degree.

Another influential War Studies alumnus at the World Service is Aliaume Leroy, producer for its Africa Eye program. Well-known BBC News presenter Sophie Long also graduated from the department, working for Reuters and ITN before joining the state broadcaster.

“It’s an open secret that King’s College London Department of War Studies operates as the finishing school for Anglo-American securocrats. So it’s maybe not a surprise that graduates of its various military and intelligence courses also enter into a world of corporate journalism that exists to launder the messaging of these same ‘security’ agencies,” Matt Kennard — an investigative journalist for Declassified U.K. who has previously exposed the university’s connections to the British state — told MintPress. “It is, however, a real and present danger to democracy. The university imprimatur gives the department’s research the patina of independence while it works, in reality, as the unofficial research arm of the U.K. Ministry of Defence,” he added.

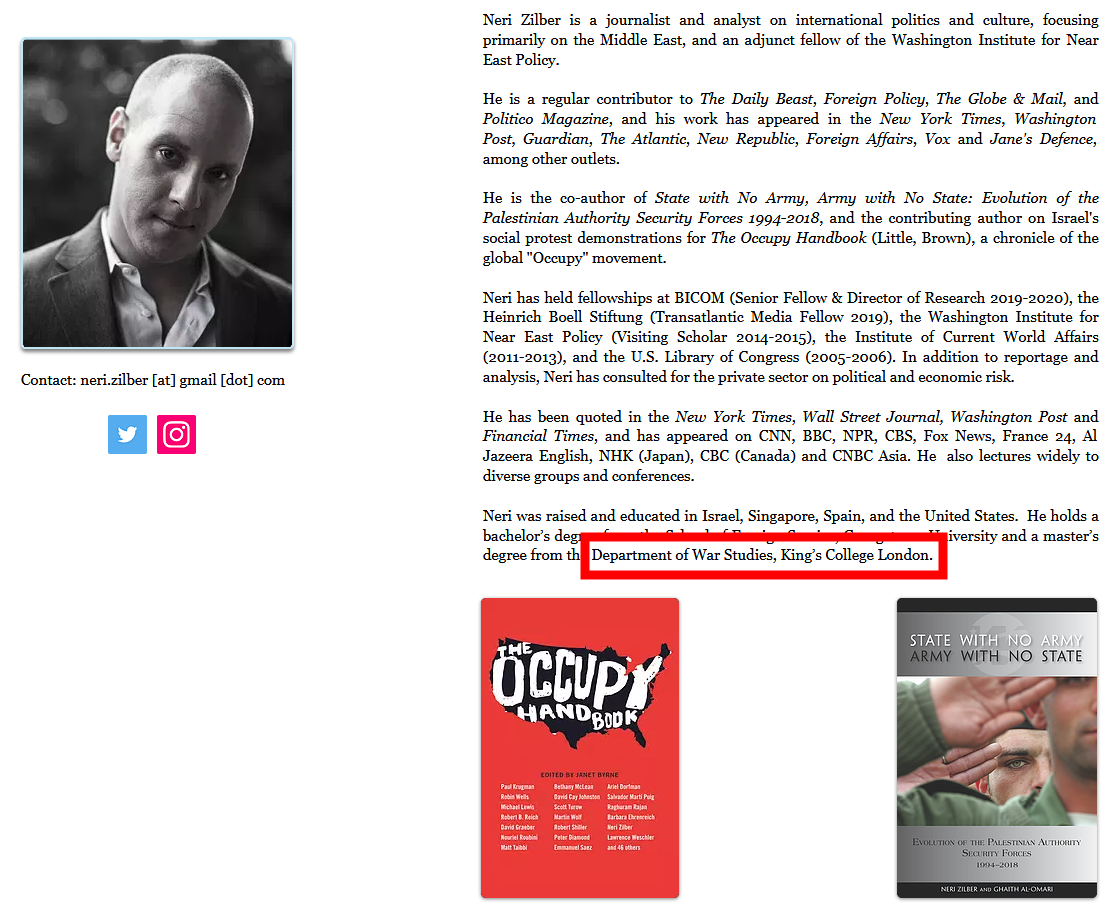

The Department of War Studies also trains many international journalists and commentators, including Nicholas Stuart of the Canberra Times (Australia); Pakistani writer Ayesha Siddiqa, whose work can be found in The New York Times, Al-Jazeera, The Hindu and many other outlets; and Israeli writer Neri Zilber, a contributor to The Daily Beast, The Guardian, Foreign Policy and Politico.

What’s it all about?

Why are so many influential figures in our media being hothoused in a department well known for its connections to state power, for its faculty being active or former military or government officials, and for producing spies and operatives for various three-letter agencies? The point of this is not to allege that these journalists are all secretly card-carrying spooks: they are not. Rather, it is to highlight the alarmingly close links between the national security state and the fourth estate we rely on to be a check on their power and to hold them accountable.

Journalists trained in this sort of environment are far more likely to see the world in the same manner as their professors do. And perhaps they would be less likely to challenge state power when the officials they are scrutinizing were their classmates or teachers.

These sorts of questions abound when such a phenomenon exists: Why are so many journalists choosing to study at this particular department, and why do so many go on to be so influential? Are they being vetted by security agencies, with or without their knowledge? How independent are they? Will they just repeat British and American state talking points, as the Department of War Studies’ publications do?

On the question of vetting, the BBC admitted that, at least until the 1990s, it conspired with domestic spying agency MI5 to make sure that people with left-wing and/or anti-war leanings, or views critical of British foreign policy and empire were secretly blocked from being hired. When pressed on whether this policy is still ongoing, the broadcaster refused to comment, citing “security issues” — a response that is unlikely to reassure skeptics.

“While it strikes me as very interesting that a single academic institution could play such a major role in the recruitment of pro-establishment activist intellectuals and delivery of the same to the media, it is not so surprising,” Oliver Boyd-Barrett, Professor Emeritus at Bowling Green State’s School of Media and Communication and an expert in collusion between government and media, told MintPress, adding:

Elite institutions in the past and doubtless still today have been major playgrounds for intelligence services. The history of the modern nation-state generally, not just the USA, seems to suggest that national unity — and therefore elite safety — is regarded by elites as achievable only through careful management and often suppression or diversion of dissent. Far more resources are typically committed to this than many citizens, drilled in the propaganda of democracy, realize or care to concede.

The Bellingcat Boys

While the journalists cataloged above are not spooks, some other Department of War Studies figures working in journalism could possibly be described as such, particularly those around the influential and increasingly notorious investigative website Bellingcat.

Cameron Colquhoun, for instance, spent almost a decade at GCHQ, Britain’s version of the NSA, where he was a senior analyst running cyber and counter-terrorism operations. He holds qualifications from both King’s College London and the State Department. This background is not disclosed in his Bellingcat profile, which merely describes him as the managing director of a private intelligence company that “conduct[s] ethical investigations” for clients around the world.

Bellingcat’s senior investigator Nick Waters spent four years as an officer in the British Army, including a tour in Afghanistan, where he furthered the British state’s objectives in the region. After that, he joined the Department of War Studies and Bellingcat.

For the longest time, Bellingcat’s founder Eliot Higgings dismissed charges that his organization was funded by the U.S. government’s National Endowment for Democracy (NED) — a CIA cutout organization — as a ridiculous “conspiracy.” Yet by 2017, he was admitting that it was true. A year later, Higgins joined the Department of War Studies as a visiting research associate. Between 2016 and 2019 he was also a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, the brains behind the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Bellingcat has received money from the following:

OSF

Meedan

NED

Adessium

Crowdfunding— Eliot Higgins (@EliotHiggins) February 6, 2017

Higgins appears to have used the university department as a recruiting ground, commissioning other War Studies graduates, such as Jacob Beeders and the aforementioned Christiaan Triebert and Aliaume Leroy, to write for his site.

Bellingcat is held in very high regard by the CIA. “I don’t want to be too dramatic, but we love [Bellingcat],” said Marc Polymeropoulos, the agency’s former deputy chief of operations for Europe and Eurasia. Other officers explained that Bellingcat could be used to outsource and legitimize anti-Russia talking points. “The greatest value of Bellingcat is that we can then go to the Russians and say ‘there you go’ [when they ask for evidence],” added former CIA Chief of Station Daniel Hoffman.

Bellingcaught

A recent MintPress investigation explored how Bellingcat acts to launder national security state talking points into the mainstream under the guise of being neutral investigative journalists themselves.

Newly leaked documents show how Bellingcat, Reuters and the BBC were covertly cooperating with the U.K.’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to undermine the Kremlin and promote regime change in Moscow. This included training journalists and promoting explicitly anti-Russian media across Eastern Europe. Unfortunately, the FCO noted, Bellingcat had been “somewhat discredited,” as it constantly spread disinformation and was willing to produce reports for anyone with money.

Nevertheless, a new European Parliament proposal published last month recommends hiring Bellingcat to assist in producing reports that would lay the groundwork for sanctioning Russia, for throwing it out of international bodies, and to “assist Russia’s transformation into a democracy.” In other words, to overthrow the government of Vladimir Putin.

An academic journalistic nexus

The Department of War Studies is also part of this pro-NATO, anti-Russia group. Quite apart from being staffed by soldiers, spooks and government officials, it puts out influential reports advising Western governments on foreign and defense policy. For instance, a study entitled “The future strategic direction of NATO” advises that member states must increase their military budgets and allow American nuclear weapons to be stored in their countries, thereby “shar[ing] the burden.” It also recommended that NATO must redouble its commitment to opposing Russia while warning that it needed urgently to form a “coherent policy” on the Chinese threat.

Other War Studies reports claim that Russia is carrying out “information-psychological warfare” through its state channels RT and Sputnik, and counsel that the West must use its technical means to prevent its citizens from consuming this foreign propaganda.

King’s College London academics have also proven crucial in keeping dissident publisher Julian Assange imprisoned. A psychiatrist who has worked with the War Studies department testified in court that the Australian was suffering only “moderate” depression and that his suicide risk was “manageable,” concluding that extraditing him to the United States “would not be unjust.” As Matt Kennard’s investigation found, the U.K. Ministry of Defence had provided £2.2 million ($3.1 million) in funding to the institute where he worked (although the psychiatrist in question claimed his work was not directly funded by the MoD).

King’s College London markets the War Studies department to both graduates and undergraduates as a stepping stone towards a career in journalism. In its “career prospects” section for its master’s course in war studies, it tells interested students that “graduates go on to work for NGOs, the FCO, the MoD, the Home Office, NATO, the UN or pursue careers in journalism, finance, academia, the diplomatic services, the armed forces and more.”

Likewise, undergraduates are told that:

You will gain an in-depth and sophisticated understanding of war and international relations, both as subjects worthy of study and as intellectual preparation for the widest possible range of career choices, including in government, journalism, research, and humanitarian and international organisations.

Courses such as “New Wars, New Media, New Journalism” fuse together journalism and intelligence and are overseen by War Studies academics.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the department has taught many influential politicians, including foreign heads of state and members of the British parliament. But at least there is considerable overlap between the fields of defense policy and politics. The fact that the very department that trains high state officials and agents of secretive three letter agencies is also the place that produces many of the journalists we rely on to stand up to those officials and keep them in check is seriously problematic.

An unhealthy respect for authority

Unfortunately, rather than challenging power, many modern media outlets amplify its message uncritically. State officials and intelligence officers are among the least trustworthy sources, journalistically speaking. Yet many of the biggest stories in recent years have been based on nothing except the hearsay of officials who would not even put their names to their claims.

The level of credulity modern journalists have for the powerful was summed up by former CNN White House Correspondent Michelle Kosinski, who last month stated that:

As an American journalist, you never expect:

-

- Your own govt to lie to you, repeatedly

- Your own govt to hide information the public has a right to know

- Your own govt to spy on your communications

Unfortunately, credulity stretches into outright collaboration with intelligence in some cases. Leaked emails show that the Los Angeles Times’ national security reporter Ken Dilanian sent his articles directly to the CIA to be edited before they were published. Far from hurting his career, however, Dilanian is now a correspondent covering national security issues for NBC News.

Boyd-Barrett said that governments are dependent on “the assistance of a penetrated, colluding and docile mainstream media which of late — and in the context of massive confusion over Internet disinformation campaigns, real and alleged — appear ever more problematic guardians of the public right to know.”

In recent years, the national security state has increased its influence over social media giants as well. In 2018, Facebook and the Atlantic Council entered a partnership whereby the Silicon Valley giant partially outsourced curation of its 2.8 billion users’ news feeds to the Council’s Digital Forensics Lab, supposedly to help stop the spread of fake news online. The result, however, has been the promotion of “trustworthy” corporate media outlets like Fox News and CNN and the penalization of independent and alternative sources, which have seen their traffic decrease precipitously. Earlier this year, Facebook also hired former NATO press officer and current Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council Ben Nimmo to be its chief of intelligence. Reddit’s Director of Policy is also a former Atlantic Council official.

Meanwhile, in 2019, a senior Twitter executive for the Middle East region was unmasked as an active duty officer in the British Army’s 77th Brigade, its unit dedicated to psychological operations and online warfare. The most notable thing about this event was the almost complete lack of attention it received from the mainstream press. Coming at a time when foreign interference online was perhaps the number one story dominating the news cycle, only one major outlet, Newsweek, even mentioned it. Furthermore, the reporter who covered the story left his job just weeks later, citing stifling top-down censorship and a culture of deference to national security interests.

The purpose of this article is not to accuse any of those mentioned of being intelligence agency plants (although at least one person did actually work as an intel officer). The point is rather to highlight that we now have a media landscape where many of the West’s most influential journalists are being trained by exactly the same people in the same department as the next generation of national security operatives.

It is hardly a good look for a healthy, open democracy that so many spies, government officials, and journalists trusted to hold them accountable on our behalf are all being shot out of the very same cannon. Learning side by side has helped to create a situation where the fourth estate has become overwhelmingly deferential to the so-called deep state, where anonymous official’s words are taken as gospel. The Department of War Studies is just one part of this wider phenomenon.

Feature photo | The Maughan Library Gate at Kings College London, UK. David JC | Alamy

Alan MacLeod is Senior Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent, as well as a number of academic articles. He has also contributed to FAIR.org, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, and Common Dreams.