Large crowds gathered in Kreeri village in Kashmir last Monday to honor the life and journalistic work of Shujaat Bukhari, the slain editor of the Rising Kashmir. Bukhari, who lived under constant threat, was gunned down as he was leaving his office last Thursday. Three heavily armed assassins on motorcycles-opened fire on him with dozens of rounds, killing the fifty-year old family man, along with two of his security guards. He was on his way home to break his Ramzan fast with his family.

Bukhari, who had already been kidnapped once and escaped, was murdered soon after he took up the case of a young man, Kaiser Bhat, who was tragically run over and killed by security forces, during one of many recent street protests in Indian-Administered Kashmir. Last tuesday, local and regional newspapers in Kashmir left large blank spaces where editorials would typically appear to honor the highly revered editor and journalist.

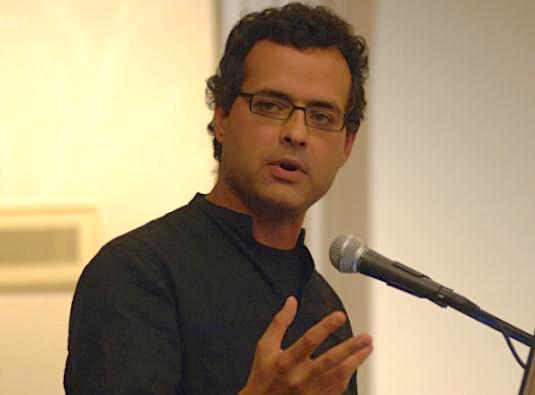

I spoke at length with writer and noted author Vijay Prashad about the life and times of Shujaat Bukhari. Prashad was a colleague of Bukhari–who was for many years the bureau chief of the Hindu newspaper where Prashad’s work also appears

Dennis Bernstein: Welcome Vijay Prashad, Good of you to do this.

Could you tell us about Shujaat Bukhari in the context of his working in that dangerous part of the world?

Vijay Prashad: Shujaat Bukhari was highly respected in Kashmir and well known in other parts of India. Shujaat was for many years the bureau chief of the Hindu newspaper, for which I write. Then he was the head of station for the magazine Frontline. These periodicals highly valued the reports Bukhari submitted from Kashmir. He was a very honest reporter, in an age when many journalists are simply stenographers who amplify the voices of the powerful. Then there are real journalists, who challenge the narrative about how the world operates. Bukhari reported in a heartfelt way on what the conflict in Kashmir meant from the standpoint of the people. Genuine journalists are an endangered species. When you set out to report about the world from the standpoint of the people, you cross the line of somebody powerful. I have seen so many friends–in Pakistan, in Afghanistan, in Turkey–killed by the state. A friend of mine who was working on the Bin Laden story was picked up by Pakistani intelligence in May of 2011 and his body was found mutilated north of Karachi.

DB: Could you explain exactly how he was murdered? I believe his murder followed his reporting of the killing of an activist, Kaiser Bhat, who was run down on the street at a protest.

VP: Let me give you some context. From the standpoint of the state and the stenographer/reporter, someone like Kaiser Bhat, who was run over by a jeep, was an aberration, a terrorist. But what Bukhari and others with great sensitivity demonstrated is that Kaiser Bhat is just an ordinary Kashmiri. He reverses the question of the burden of proof: We don’t have to wonder why Kaiser Bhat became a militant. What we should wonder about is why all the other young people don’t become militants. The context of Kashmir almost demands that the population rise up in revolt. The Indian state certainly didn’t appreciate the kind of reporting that Bukhari was doing on Kashmir. It was also reporting that the militants didn’t always appreciate. He was also critical of the way that some militant groups had inflamed the situation, working for their own advantage rather than the will of the people. He was killed by masked gunmen who came on a motorcycle. It is unlikely that they will be caught or that their handlers will be identified. But whether or not we are able to establish forensically who killed Bukhari, we know who killed him. It was people in power who were threatened by the honesty of this very brave journalist.

DB: This was not the first threat to this courageous journalist. He was kidnapped in the past.

VP: Those who have reported from areas of great conflict know the dangers very well. After he was abducted, he made a statement to the effect that he didn’t know who the enemies were. When someone points a gun at you, you don’t know whose gun it is. You’re not out there to have a debate with the person. If some militia group stops you at a checkpoint and puts a gun to your head, you’re not thinking about which side you are on. You’re thinking, this is the end of my life. Remember that this is not just about a checkpoint in the middle of nowhere. It is also the United States, which targeted the Al Jazeera office in the Palestine hotel in Baghdad during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. This is a serious issue, this disregard for the person who is out there to get the story. We know that control of the story is a very important part of warfare. Going after reporters who are trying to tell different stories is very much a part of the agenda of war-making.

DB: For those listeners who don’t know a great deal about Kashmir, could you describe how dangerous it is there?

VP: The region is a vast and beautiful place. There are Muslims of all kinds of different traditions. There are Hindus, there are Buddhists. They also define themselves in terms of ethnicity and culture. It is a very complex place. Sadly, in 1947-1948 the new government of Pakistan couldn’t come to terms with what was happening in Kashmir. There was no appreciation of the self-determination of the Kashmiri people. Both the new states of India and Pakistan captured territory. Pakistan holds about a third of the Kashmiri region and India holds about two-thirds. China took a section of it in a war against India in 1962.

The people of Kashmir have felt alienated from the Indian state. Kashmir has erupted on several occasions, where people have protested against Indian state control. The framework is that Kashmir is a security problem and that Pakistan is infiltrating to create problems there. Some of this, of course, is true. But the core issue isn’t Pakistan’s involvement in Kashmir. The core issue is the alienation of the Kashmiri people. This exploded in a massive uprising in the 1980’s, which mirrored the First Palestinian Intifada. The Freedom Movement that began in 1989 was met with immense force. Right now that are between 700,000 and one million Indian troops in the Kashmir Valley. By the count of the Indian government, there are only 150 militants. That is an awfully strange ratio. This highly militarized region resembles an occupation. The people’s interface with the Indian state is not in the form of a postman or a social worker. It is a military officer. Until the Indian government comes to terms with the fact that you cannot allow a state’s primary interface with the population to be a soldier and allow security to be the main framework, until you come to terms with that and create an alternative framework, there is no solution to the Kashmir problem.

DB: Gives us your assessment of this latest wave of resistance in Gaza.

VP: The attention has been on Gaza, on the perimeter fence. It is very difficult for the Israeli government to turn its eyes away from this. It will breed callousness if the Israeli public doesn’t rise up in revolt against this. But it is not only in Gaza. Interestingly, in the West Bank, which had been politically quite quiet for a long time, we have seen in the last few weeks people coming out on the streets who are disgusted by what they are seeing, not only in Gaza but also with the US embassy moving to Jerusalem and the seizure of East Jerusalem. We are seeing a new hunger in the Palestinian communities for a new project. What people are coming to terms with is that the national liberation project has exhausted itself. This was clear already in the famous prisoners’ letter of 2004. Now there needs to be a new agenda to come to terms with the new reality. It is very unlikely that a two-state solution is possible. What else is possible? There has to be some clear-headed thinking. You cannot simply have an emotional reaction. New grassroots formations need to emerge, and what we have seen in the West Bank recently–with the farmers’ union and the small trade union and various other worker and peasant organizations coming out onto the streets–is a very encouraging sign. It means that the people’s organizations are taking the initiative. I hope they articulate an agenda for their own politics, because Palestine needs a new politics.

DB: It is interesting to think about Jordan in this context. Palestinians are a large part of the population there. They are trying to play both ends to the middle, in a way.

VP: You are very correct. I think that the protests which took place in Amman and in other cities could not have been imagined as recently as 2011, during the Arab Spring. The immediate cause of the protests was the raising of taxes by the government. A cross-class alliance developed to protest this. But this was merely the spark that brought people onto the streets. There is something deeper here. The Jordanian ruling class has had a very curious subordinate position regarding Saudi Arabia, the United States and Israel. When there are protests in Ramallah, for instance, on the other side of the Jordan River, in Jordan itself there is quiet. Why hasn’t the Jordanian monarchy been much more forthright in denouncing the massacre at the Gaza perimeter fence? We shouldn’t assume that this is merely about taxes, a bread and butter issue. There is also something decisively political here, a disgruntlement with the monarchy. The ability to move an alternative agenda is so narrow in Jordan. I don’t foresee a rupture with the Saudis and the Americans and the Israelis. It poses a difficult question for the monarchy in Jordan. It balances on the one side this camp of the Saudis, the Americans and the Israelis, and on the other side its own population, which doesn’t like this alliance. What we get are these changes of cabinet, but there is no long-term solution for Jordan.

DB: The Trump administration is really emerging as a white supremacist operation. It is taking the immigration apparatus set up under Obama and taking it to the next level. What are your thoughts on the separation of families at the border?

VP: There is no question that Trump’s policies are quite disgusting. I am happy that people in the United States are pushing back. But this goes back to the seizing of Native American children, putting them into concentration camps. Slave children snatched from their families. This is an old story in American history, which the country has never accounted for. This is a much deeper problem than Trump or Obama. This is deep in the American structure. I think it is about time that the country confront the ugly truth about slavery. Entire families were destroyed. Concepts like love were taken away from people of African descent. What happens to their children, who are seen as the property of the master? How is that different from what Trump is doing now?

DB: We see US reporters getting very worked up about the breaking up of families, but they don’t seem to care very much when the Israelis have a policy of arresting and torturing children and breaking up families, which is very difficult not to notice.

VP: It partly has to do with a certain kind of arrogance, that America is better than this. But actually, this is exactly what America is. If you say that we are exceptional and if you say that the Israelis have to do it for security reasons, then you can forgive the Israelis at the same time that you claim to be different. Ann Coulter, for instance, said yesterday that the children coming across the border are child actors. This is the same attitude of the hardest hearts in Israel. Unless the people protest against such actions of their government, the soul of that society is going to atrophy and it will no longer have the ability to be compassionate. That is what is happening in Israel. And, of course, it is part of the sclerosis that has infected American culture as well.

Dennis J. Bernstein is a host of “Flashpoints” on the Pacifica radio network and the author of Special Ed: Voices from a Hidden Classroom. You can access the audio archives at www.flashpoints.net. You can get in touch with the author at [email protected].

Top Photo | Indian Army soldiers carry out a search operation for suspected rebels during a gunbattle at Hardshoora village, 35 kilometers (20 miles) north of Srinagar, India, Thursday, April 2, 2015. Suspected Kashmiri rebels and Indian security personnel were engaged in a fierce gunbattle Thursday in the Himalayan territory, officials said.

Source | Consortium News