A new global geopolitical game is in formation, and the Middle East, as is often the case, will be directly impacted by it in terms of possible new alliances and resulting power paradigms. While it is too early to fully appreciate the impact of the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war on the region, it is obvious that some countries are placed in relatively comfortable positions in terms of leveraging their strong economies, strategic location and political influence. Others, especially non-state actors, like the Palestinians, are in an unenviable position.

Despite repeated calls on the Palestinian Authority by the US Biden Administration and some EU countries to condemn Russia following its military intervention in Ukraine on February 24, the PA has refrained from doing so. Analyst Hani al-Masri was quoted in Axios as saying that the Palestinian leadership understands that condemning Russia “means that the Palestinians would lose a major ally and supporter of their political positions.” Indeed, joining the anti-Russia western chorus would further isolate an already isolated Palestine, desperate for allies who are capable of balancing out the pro-Israel agenda at US-controlled international institutions, like the UN Security Council.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the dismantling of its Eastern Bloc in the late 1980s, Russia was allowed to play a role, however minor, in the US political agenda in Palestine and Israel. It participated, as a co-sponsor, in the Madrid peace talks in 1991, and in the 1993 Oslo accords. Since then a Russian representative took part in every major agreement related to the ‘peace process,’ to the extent that Russia was one of the main parties in the so-called Middle East Quartet which, in 2016, purportedly attempted to negotiate a political breakthrough between the Israeli government and the Palestinian leadership.

Despite the permanent presence of Russia at the Palestine-Israel political table, Moscow has played a subordinate position. It was Washington that largely determined the momentum, time, place and even the outcomes of the ‘peace talks.’ Considering Washington’s strong support for Tel Aviv, Palestinians remained occupied and oppressed, while Israel’s colonial settlement enterprises grew exponentially in terms of size, population and economic power.

Palestinians, however, continued to see Moscow as an ally. Within the largely defunct Quartet – which, aside from Russia, includes the US, the European Union and the United Nations – Russia is the only party that, from a Palestinian viewpoint, was trustworthy. However, considering the US near complete hegemony on international decision-making, through its UN vetoes, massive funding of the Israeli military and relentless pressure on the Palestinians, Russia’s role proved ultimately immaterial, if not symbolic.

There were exceptions to this rule. In recent years, Russia has attempted to challenge its traditional role in the peace process as a supporting political actor, by offering to mediate, not just between Israel and the PA, but also between Palestinian political groups, Hamas and Fatah. Using the political space that presented itself following the Trump Administration’s cutting of funds to the PA in February 2019, Moscow drew even closer to the Palestinian leadership.

A more independent Russian position in Palestine and Israel has been taking shape for years. In February 2017, for example, Russia hosted a national dialogue conference between Palestinian rivals. Though the Moscow conference did not lead to anything substantive, it allowed Russia to challenge its old position in Palestine, and the US’ proclaimed role as an ‘honest peace broker.’

Wary of Russia’s infringement on its political territory in the Middle East, US President Joe Biden was quick to restore his government’s funding of the PA in April 2021. The American President, however, did not reverse some of the major US concessions to Israel made by the Trump Administration, including the recognition of Jerusalem, contrary to international law, as Israel’s capital. Moreover, under Israeli pressure, the US is yet to restore its Consulate in East Jerusalem, which was shut down by Trump in 2019. The Consulate served the role of Washington’s diplomatic mission in Palestine.

Washington’s significance to Palestinians, at present, is confined to financial support. Concurrently, the US continues to serve the role of Israel’s main benefactor financially, militarily, politically and diplomatically.

While Palestinian groups, whether Islamists or socialists, have repeatedly called on the PA to liberate itself from its near-total dependency on Washington, the Palestinian leadership refused. For the PA, defying the US in the current geopolitical order is a form of political suicide.

But the Middle East has been rapidly changing. The US political divestment from the region in recent years has allowed other political actors, like China and Russia, to slowly immerse themselves as political, military and economic alternatives and partners.

The Russian and Chinese influence can now be felt across the Middle East. However, their impact on the balances of power in the Palestine-Israel issue, in particular, remains largely minimal. Despite its strategic ‘pivot to Asia’ in 2012, Washington remained entrenched behind Israel, because American support for Israel is no longer a matter of foreign policy priorities, but an internal American issue involving both parties, powerful pro-Israel lobby and pressure groups, and a massive rightwing, Christian constituency across the US.

Palestinians – people, leadership and political parties – have little trust or faith in Washington. In fact, much of the political discord among Palestinians is directly linked to this very issue. Alas, walking away from the US camp requires a strong political will that the PA does not possess.

Since the rise of the US as the world’s only superpower over three decades ago, the Palestinian leadership reoriented itself entirely to be part of the ‘new world order’. The Palestinian people, however, gained little from their leadership’s strategic choice. To the contrary, since then the Palestinian cause suffered numerous losses – factionalism and disunity at home, and a confused regional and international political outlook, thus the hemorrhaging of Palestine’s historic allies, including many African, Asian and South American countries.

The Russia-Ukraine war, however, is placing the Palestinians before one of their greatest foreign policy challenges since the collapse of the Soviet Union. For Palestinians, neutrality is not an option since the latter is a privilege that can only be obtained by those who can navigate global polarization using their own political leverage. The Palestinian leadership, thanks to its selfish choices and lack of a collective strategy, has no such leverage.

Common sense dictates that Palestinians must develop a unified front to cope with the massive changes underway in the world, changes that will eventually yield a whole new geopolitical reality.

The Palestinians cannot afford to stand aside and pretend that they will magically be able to weather the storm.

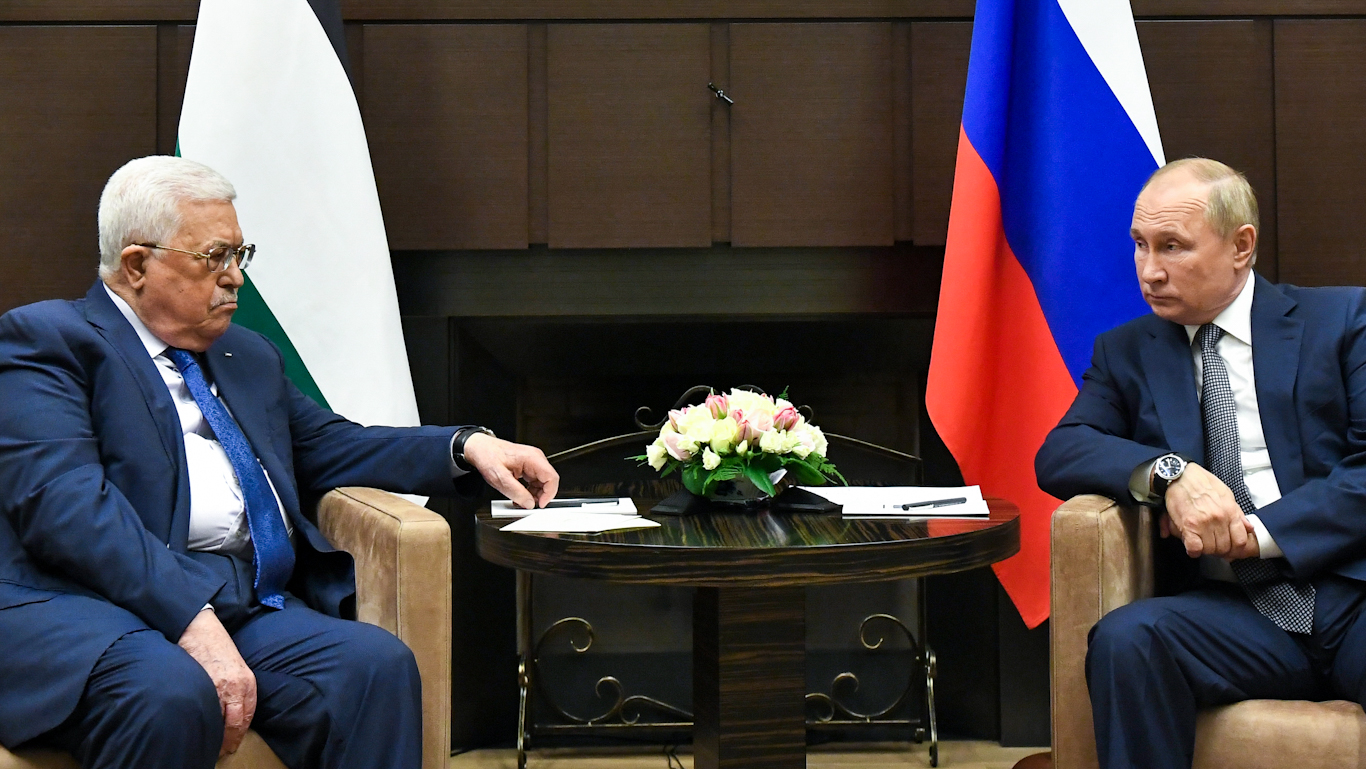

Feature photo | Russian President Vladimir Putin, right, and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas talk to each other during their meeting in the Bocharov Ruchei residence in the Black Sea resort of Sochi, Russia, Nov. 23, 2021. Yevgeny Biyatov | Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP

Dr. Ramzy Baroud is a journalist and the Editor of The Palestine Chronicle. He is the author of six books. His latest book, co-edited with Ilan Pappé, is “Our Vision for Liberation: Engaged Palestinian Leaders and Intellectuals Speak out”. Baroud is a Non-resident Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Islam and Global Affairs (CIGA). His website is www.ramzybaroud.net