NEW YORK — Former San Francisco 49ers quarterback-turned-activist Colin Kaepernick visited inmates held at New York’s Rikers Island on Thursday, December 14 “to share a message of hope and inspiration,” according to New York City Department of Corrections spokesman Peter Thorne. Eric Phillips, a spokesman for the mayor’s office, said Kaepernick “should be applauded” for using his celebrity status “to help young adults turn their lives around.”

Persons awaiting pre-trial detention, as well as those who have been given relatively short sentences are housed at Rikers Island, a 400-acre land mass located in the East River across from LaGuardia Airport. The facility is notorious for the violence endemic there.

Most recently Rikers was known as the place where 22-year old Kalief Browder spent three years of his life because he could not afford to make bail on a theft charge. Browder, who was 16 at the time was sent to Rikers, spent much of his time in isolation and suffered abuse from both inmates and guards. The charges against Browder would ultimately be dropped, but he committed suicide two years after his release from the jail.

Kaepernick’s “ilk”

It would seem that a place like Rikers could use its famous visitor’s message of hope. But Kaepernick’s visit didn’t sit well with Rikers correctional officers. They complained that someone of Kaepernick’s “ilk” sends the wrong message to the jail’s 11,000 inmates: that it’s okay to attack their jailers.

“This will only encourage inmates to continue to attack Correction Officers at a time when we need more protection,” said Elias Husamudeen, president of the Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association.

Read more by Thandisizwe Chimurenga

“The inmates see a guy like this coming in, it’s almost like the administration is condoning being anti-law enforcement,” said Patrick Ferraiuolo, president of the Correction Captains’ Association. “His presence alone could incite these guys. We’ve got enough issues in the facility with inmates assaulting staff,” Ferraiuolo said. “His presence, what he stands for, certainly doesn’t help.”

Kaepernick has become an increasingly visible activist against injustice in the past year, since he began a national anthem kneeling protest against police brutality. Most recently he was honored with Sports Illustrated’s Muhammad Ali Legacy Award. In addition to maintaining his stance on police brutality against unarmed African-Americans, Kaepernick has also been proactive in other areas.

He has conducted a “know your rights” workshop for San Francisco Bay Area youth; donated business suits to former prisoners to assist in their reentry efforts; and donated monies to help black veterans with job placement and housing, as well as to the Meals on Wheels program that feeds senior citizens and others in need.

A history of violence

Like their law enforcement counterparts in the outside world, correctional officers often present themselves as victims instead of aggressors. Yet an October 2016 report, by the monitor appointed by a federal court earlier that year, found that attacks by guards at Rikers were on the increase:

Inmates are regularly subjected to head strikes, wall slams and violent takedowns often involving neck/chokeholds, [leading to injuries that are] followed by delays in providing needed medical attention.”

The report also found that guards will regularly strike inmates who are restrained in handcuffs and that there is a tendency to use pepper-spray, often in large doses and at close range, in response to minor altercations. And violent incidents at the controversial facility appear to be increasing: in December of 2016, there were 3.93 uses of force for every 100 inmates, compared to 3.73 in November of 2015.

October 2017 saw no decrease in correctional officer violence, according to the most recent study on the facility. That report, compiled by an eight-member group to monitor adherence to a court case dating back to 2011, stated that jail staff “relish confrontation,” and too often “engender, nurture and encourage confrontation.” Avoiding confrontation, the group said, “appears anathema to many supervisors and line staff.”

The 259-page report, which covered the period Jan. 1 to June 30 of this year, noted 423 use-of-force instances. Of those, 100 were against already-restrained inmates.

A number of former Rikers Island correctional staff have since become guests of the institution. September 2016 saw the conviction of six former guards for the beating of a man who had mouthed off to an officer, and the subsequent cover-up of the incident. Convicted of first-degree attempted gang assault and other charges, the former officers will spend four and a half to six and a half years at Rikers.

This past September, a former guard was sentenced to 30 years in prison for repeatedly kicking a mentally ill inmate in the head. The inmate was held down by other officers during the assault. Another former guard is currently facing a 30-year sentence for repeatedly punching a handcuffed inmate in the face. The officer, who was caught on video during the assault, lied about the incident in his report.

With all hope of rehabilitating the institution seemingly lost, current New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio has said that the jail will be closed within the next 10 years. The move can’t come soon enough.

Watch | Violence Inside Rikers

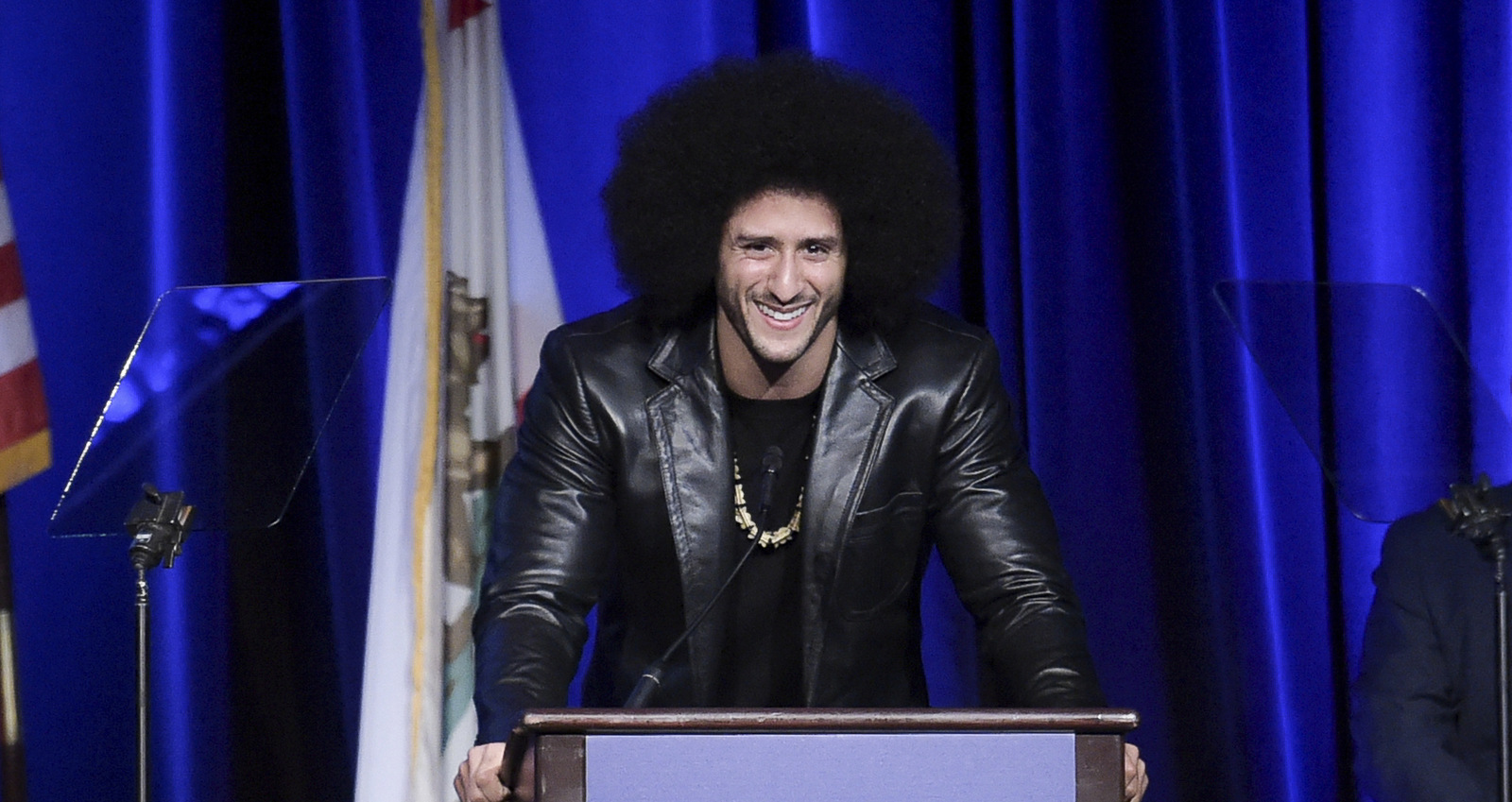

Top photo | Colin Kaepernick attends the 2017 ACLU SoCal’s Bill of Rights Dinner at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel on Sunday, Dec. 3, 2017, in Beverly Hills, Calif. (Photo: Richard Shotwell/Invision/AP)

Thandisizwe Chimurenga is an award-winning, freelance journalist based in Los Angeles, California. She is a staff writer for MintPress News, Daily Kos and co-hosts a weekly, morning drive-time public affairs/news show on the Pacifica Radio network. She is the author of No Doubt: The Murder(s) of Oscar Grant and Reparations … Not Yet: A Case for Reparations and Why We Must Wait; she is also a contributor to several social justice anthologies