This month’s passing of legendary Oscar-winning actor and film director Maximilian Schell at the age of 83 marked the end of an era for me: Maximilian was the last of the German-speaking actors who shared the silver screen with my father, Norbert Schiller.

When Maximilian was born in 1930, my father was well on his way to becoming one of Europe’s most acclaimed classical actors. By the time my father fled Germany for Switzerland in 1937, he had set the record for playing Romeo in Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” the most times on the German stage.

Unaware of my father’s Jewish ancestry, even Adolf Hitler took an interest in him. After seeing my father play Romeo in Frankfurt, Hitler announced that he was going backstage to personally congratulate him. My father saw the evil in Hitler very early on and wanted nothing to do with him, so when he found out Hitler was coming backstage, my father exited through the back door.

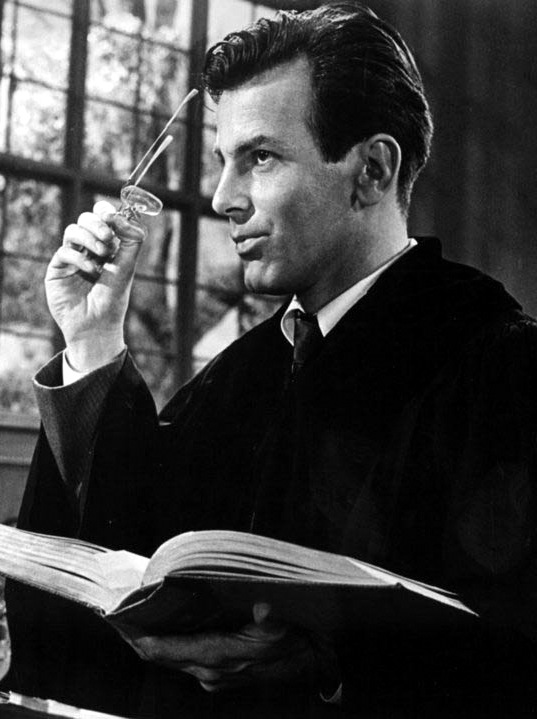

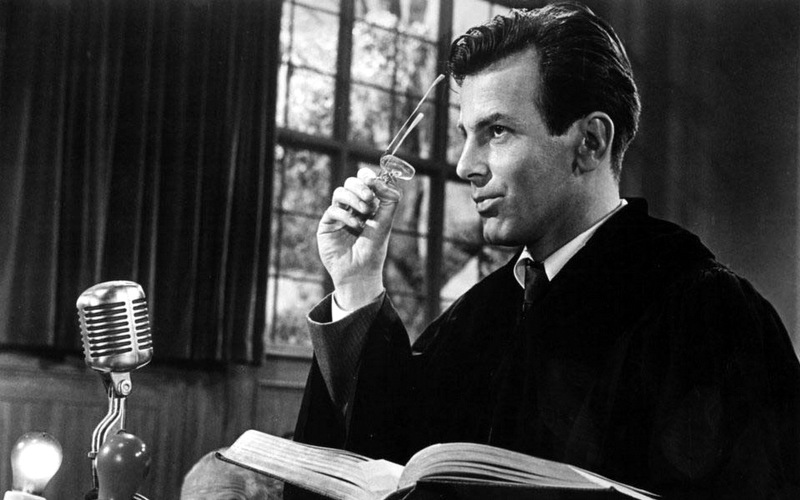

From what I have been told, Maximilian and my father first met during the making of “Judgment at Nuremberg” in 1960. My father had a minor role as a waiter in the film, but Maximilian earned an Oscar for his portrayal of Hans Rolfe, a German defense lawyer.

Nevertheless, Maximilian would have been well aware of my father’s reputation on the German stage and likely joined him during breaks in filming to recite poems by Goethe. I wouldn’t surprised if my father mixed in the same theatrical circles as Maximilian’s parents during the 1920s and 30s. Whatever brought the two Austrian-born actors together during the filming of “Judgment at Nuremberg,” they remained the best of friends until my father’s death in 1988 at the ripe old age of 88.

My earliest recollections of Maximilian are at our home in Santa Barbara, when I was a young boy. He stayed at the Chateau Marmont above the Sunset Strip in West Hollywood every time he came to Hollywood to work on a film. When he wanted a break from the Hollywood madness, he would make the two-hour drive north to our home in Santa Barbara to visit with my father.

My father never fully embraced the American dream of owning a big car and a big house. In fact, by the time I was born my father had stopped driving altogether, preferring to walk, use public transportation or rely on my mother to take him where he needed to go. Instead of living in a large American-style home with a huge manicured lawn, he opted for a small, unimposing house that was barely big enough for our family of four, not to mention the friends and relatives who visited frequently.

The house was U-shaped, with the opening of the “U” closed off by the garage. In the middle was a small private courtyard full of shrubs, flowers and a few fruit trees that reminded my father of the homes in southern Europe.

When Maximilian came for visits, he loved to take off his shirt, recline on the chaise lounge in the center of the courtyard surrounded by the small garden and listen to my father recite German poetry. Maximilian had an unquenchable thirst for fresh juice, so my mother would rush into the kitchen between readings to squeeze fresh orange juice.

Sometimes Maximilian would come alone, or sometimes he would bring his older sister, actress Maria Schell. He would occasionally show up with a lovely young woman in tow. Though he was a “movie star” in the eyes of the public, in our tiny little courtyard, out of the spotlight, he was just Max.

Unlike many German-speaking actors, directors and producers that immigrated to America during the war years, my father never fully integrated into the Hollywood scene. He was an outsider from day one — and it didn’t help that he couldn’t shake his strong accent or his “Austrian-ness.” Unlike other German immigrants, he stuck to his principles and refused to take Nazi roles, even if it meant passing up a leading role with a big paycheck.

Though he made over 100 film and television appearances over the course of four decades, my father never had a single leading role. He never seemed upset about this, but I’m sure that deep down he missed the attention that he received on the German stage in his prime.

As my father’s film career was winding down in the 1970s, Max called him back to Europe on three different occasions to work on movies that he was directing. In 1973, Max gave my father a small role in “The Pedestrian.” He played himself: an actor returning to Austria after decades of living in America. In 1975, Max gave my father another small part in “End of the Game,” starring John Voight and Jacqueline Bisset. Finally, in 1978, Max gave my 78-year-old father his final role in “Tales from the Vienna Woods.”

I can still remember how nervous my father was just before he left for Europe to make “Tales from the Vienna Woods.” He had initially turned down the part, because he felt he couldn’t handle the travel or the pressures that came with acting in a film at his age. However, after receiving encouragement from my mother and I, and on Max’s insistence, my father reluctantly boarded the plane for what would be not only his last film but also his last visit to his motherland, Austria.

Even though it wasn’t a leading role, Max gave my father a part that suited him perfectly. Every time I see the film, I’m struck by how similar in personality my father is to the character he portrays.

Max could have chosen any of a number of European actors to play the roles my father played in his films, but he didn’t. I strongly believe that Max not only drew inspiration from my father’s ability as a classical stage actor, but also from my father’s inability to conform to Hollywood and the confines of motion pictures. I don’t think my father could fully grasp the word “cut.” For my father, acting meant continuing in character until the end of a given scene. I remember watching him on the set of a movie when I was young and seeing the agitated look he got in his eyes when the director would cut him off.

It’s hard for me to believe that Maximilian Schell died a quarter of a century after my father. It almost seems like yesterday when Max looked up at me from the chaise lounge and asked, “So Norby, what do what to be when you grow up?”

I hesitated, looked at my mother, and she suddenly blurted out, “Don’t look at me. Ask Max.”

“I want to be an actor someday,” I said sheepishly.

“You do, very well, it takes lots of hard work,” he replied before closing his eyes as my father continued reciting verses from Faust.