Wednesday marked the 50th anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066. The order gave the Department of War the authority to “exclude any and all persons” from any areas deemed vulnerable to espionage or attack. Two months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and fueled by a half-century of racism, the military decided that the American West Coast and the Arizona border would be classified as an exclusion zone.

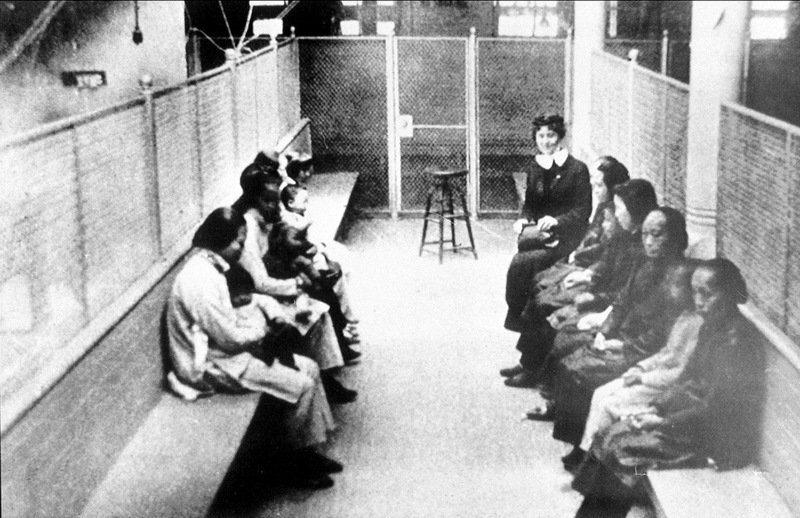

The military moved to evacuate and segregate more than 127,000 Japanese-Americans as “threats to national security.” Of those that were interned, however, none had criminal records and 62 percent were American citizens by virtue of being born in the United States. The internment reflected the national degradation and dehumanization of an entire race and remains one of the nation’s most shameful acts.

Roosevelt signed the order despite the pitched and fervent objections of his Cabinet. A month before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Curtis Munson, an investigator for the U.S. State Department, concluded that there was little to no evidence suggesting that Japanese-Americans would be loyal to Japan in the event of war.

“They have made this their home,” Munson wrote about Issei — or, first generation Japanese immigrants — who could not become citizens because of an anti-Asian exclusion law. “They have brought up children here, their wealth accumulated by hard labor is here, and many would have become American citizens had they been allowed to do so.” Their children — Nisei, or second-generation Japanese-Americans– showed an “eagerness to be Americans.”

The effect of racism

In signing the order, Roosevelt was acting partly in response to the Niihau Incident, in which three Japanese-Americans were found offering aid to a crashed Pearl Harbor bomber.

Roosevelt’s response was also influenced by growing anti-Japanese sentiment on the Pacific Coast. No Japanese-Americans were interned east of the Mississippi River, while Hawaii, which had the largest population of Japanese descendents of any American state or territory, only saw 1 percent of its Japanese-American population interned.

“We’re charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons. We do,” wrote Austin Anson, managing secretary of the Salinas Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association, to the Saturday Evening Post in May 1942. “It’s a question of whether the white man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown men. They came into this valley to work, and they stayed to take over. … They undersell the white man in the markets. … They work their women and children while the white farmer has to pay wages for his help,. If all the Japs were removed tomorrow, we’d never miss them in two weeks, because the white farmers can take over and produce everything the Jap grows. And we don’t want them back when the war ends, either.”

Racism against the Japanese in America started in 1861, when President Abraham Lincoln appointed Anson Burlingame as minister to the Qing Empire (present-day China). Lincoln’s intentions were to create a cooperative channel between the Qing Empire and the United States without resorting to violence in the same way the British did during the Opium Wars. The result of Burlingame’s diplomacy was the Burlingame-Seward treaty of 1968, which granted the United States most favored nation status with the Qing Empire.

In exchange, the United States would open up and promote Chinese immigration, provided that “citizens of the United States in China of every religious persuasion and Chinese subjects in the United States shall enjoy entire liberty of conscience and shall be exempt from all disability or persecution on account of their religious faith or worship in either country.” Naturalization, however, was denied for the Chinese and — by extension — all immigrants of Asiatic descent. These exclusion laws would not be repealed until 1943.

“Yellow Peril”

This “Yellow Peril,” in which there was a fear — especially on the West Coast — that the mass immigration of East Asians would lead to a loss of wages, a decline in standards of living, and in states such as California, a subjugation of American culture with a foreign one where the Chinese and the Japanese held societal status equivalent to African-Americans in the South.

In 1913, for example, California passed the Alien Land Law, which specifically prohibited Japanese-American land ownership in the state. Repealed by voter initiative in 1956, the law was recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court as being anti-Japanese by design.

“This measure, though limited to agricultural lands, represented the first official act of discrimination aimed at the Japanese . . . The immediate purpose, of course, was to restrict Japanese farm competition,” the court wrote in its majority decision in the case of the State of California v. Oyama (1948). “The more basic purpose of the statute was to irritate the Japanese, to make economic life in California as uncomfortable and unprofitable for them as legally possible.

“Vigorous enforcement of the Alien Land Law has been but one of the cruel discriminatory actions which have marked this nation’s treatment since 1941 of those residents who chanced to be of Japanese origin. Can a state disregard in this manner the historic ideal that those within the borders of this nation are not to be denied rights and privileges because they are of a particular race? I say that it cannot.”

The Japanese defeat of the Russians in the Russo-Japanese War, the 1931 Japanese invasion of China and the resulting annexation of Manchuria, as well as situations such as the Nanking Massacre — in which tens of thousands of Chinese civilians were murdered by the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War — helped to harden Americans’ opinions of Japan and the Japanese. The bombing of Pearl Harbor, however, was the tipping point toward the establishment of a groupthink that saw the Japanese as animals. With reports coming in about Japan’s mistreatment of prisoners of war during World War II, most Americans at the time felt justified in looking down at the Japanese.

This attitude led to a low rate of Japanese POWs captured by the Americans and ultimately, the dropping of thermonuclear bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. While Italian-Americans and German-Americans were also interned, it was not on the same scale as Japanese-American internment.

Groupthink and Dr. Seuss

One example of the groupthink during World War II is Dr. Seuss. The beloved children’s book writer and cartoonist born Theodor Seuss Geisel was a Roosevelt-supporting liberal Democrat who spoke for equal rights. However, despite his progressive tendencies, he fully supported the internment camps.

In the book “Dr. Seuss Goes to War,” Geisel was quoted as saying: “But right now, when the Japs are planting their hatchets in our skulls, it seems like a hell of a time for us to smile and warble: ‘Brothers!’ It is a rather flabby battle cry. If we want to win, we’ve got to kill Japs, whether it depresses John Haynes Holmes or not. We can get palsy-walsy afterward with those that are left.”

During the war, Geisel committed to drawing over 400 political cartoons for the New York City newspaper PM. While critical of isolationists, Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, Geisel summarily classified all Japanese-Americans as “fifth-columnists” or traitors-in-waiting. His caricatures of Hitler and Mussolini were always respectful in composition, but his depiction of Japanese figures were stereotypical, with overgrown front teeth and slanted, closed eyes — even when presented in the same cartoon with Hitler.

After the war and after the anti-Japanese fervor started to die down, Geisel felt remorse for his role in the wartime propaganda that reflected monsters that did not really exist. As a way of allegorizing the American occupation of Japan and apologizing by proxy, Geisel wrote “Horton Hears a Who!,” which he dedicated to a Japanese friend. The line, “A person’s a person no matter how small,” reflects Geisel’s about-face on how he saw the Japanese.

Today, very few have explicit racial views against the Japanese. During the Japanese craze of the 80s, a large number of Japanese companies bought American corporate assets. Japanese animosity re-blossomed briefly, though not to the extent observed in the early part of the century. However, getting past the scars of America’s “national security” measure has proven more difficult.

After being released, many of the internees were left with just the $25 the government gave them upon their exit and a free train ride. Many were forced to sell their belongings shortly after receiving the evacuation order — usually as a loss. The property they did bring with them to the camps had mostly been destroyed in the military’s custody. The government offered 10 percent reimbursement on loss incurred, but only if valid tax records could prove the loss. This was difficult, as the IRS had destroyed the tax records of many of the internees in 1943.

Many of the returning Japanese-Americans found their towns rejecting them. Jobs and educational opportunities were unavailable. Many were forced to move to cities with larger Japanese communities or to the East Coast.

While the nation would eventually make redress and formally apologize, it still serves as a reminder of what can happen when a nation grows to disregard an entire class of people.