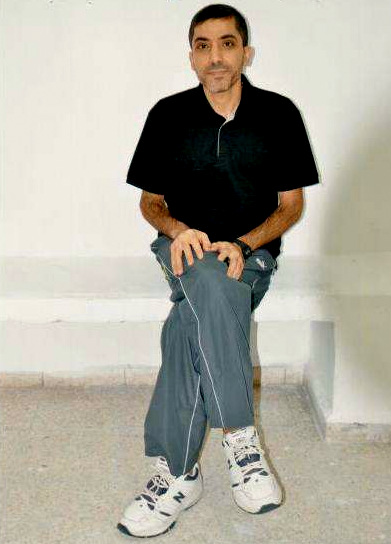

SEATTLE — Last month, an Israeli judicial panel sentenced Dirar Abu Sisi, a 46-year-old civil engineer, to 21 years in prison for aiding Hamas’ rocket program. This plea deal capped a four-year ordeal that began with Abu Sisi’s unprecedented kidnapping on a train bound for Kiev in the dead of a Ukrainian winter in February 2011.

The Mossad, Israel’s spy agency, and Ukrainian security agents collaborated to arrest Abu Sisi. After his interrogation, he was flown to an Israeli prison. Some reports even claim he was drugged and placed inside a coffin, then shipped as a “corpse” to Israel.

When this story broke, the CIA’s extraordinary rendition of terror suspects to secret torture sites was major news. Though Abu Sisi’s kidnapping wasn’t reported in this context (except by me), it is one of a number of such extrajudicial kidnappings carried out by Israel going all the way back to Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi leader found living under an alias in Argentina decades after the war had ended. A large Mossad team led by Rafi Eitan kidnapped Eichmann and flew him to Israel via El Al. The Guardian reported in 2012: “He was passed off as a sick airline employee, dressed in an El Al uniform and heavily sedated in a first class seat.”

I was the first journalist outside Ukraine to report Abu Sisi had been kidnapped and to identify him by name. Israeli journalists could not report the story because security cases are routinely placed under military censorship or hit with gag orders that prohibit suspects’ names from being reported.

He was charged with masterminding Hamas’ missile engineering program. The Israel Security Agency, or Shin Bet, and prosecution spun tall-tales of Abu Sisi operating a Gaza version of West Point for terrorists under the tutelage of the infamous Mohammed Deif, the leader of the Qassam Brigades, Hamas’ military branch. Other reports claimed he was a key operative involved in the capture and detention of Gilad Shalit.

In the course of four years of legal jockeying, Abu Sisi’s attorney, Tal Linoy, who I interviewed extensively for this article, said the only evidence ever presented were his client’s alleged confessions. These were obtained illegally and under a standard Shabak torture regimen employed routinely in such security cases. The state never presented any independent evidence.

Under Israeli security law, in the preliminary stages of a case the state may deny the defense access to evidence if it deems that evidence so sensitive that sharing it could damage state security. Though defense lawyers have security clearances permitting them, theoretically, to see such material, the security services do not take this into account. When there is secret evidence, the judge reviews it alone and makes a determination without any input from the defense. Judges generally do not overrule the prosecution and permit access to the material for defense counsel.

Linoy repeatedly appealed to the court for at least a summary of the evidence being withheld from him. After much legal obfuscation by the prosecution, he was finally offered a truncated version of the state’s case, minus original documents or any first-hand evidence. He told MintPress he is forbidden from revealing what he learned, though he could say that the public version of the charges against his client have nothing to do with the actual reason for his arrest.

One credible theory of the case which several knowledgeable sources have confirmed is that Hamas sought revenge against Abu Sisi for refusing to continue his collaboration. Through fortuitous leaks and enticements, they “arranged” for the Mossad to learn that Abu Sisi played a key role in the capture and detention of Gilad Shalit, an IDF soldier captured in a cross-border raid and held by Hamas for five years until a prisoner exchange was negotiated with Israel. Hamas knew the Israelis would apprehend such a figure and make his life miserable, which is precisely what has happened.

If the Mossad was fooled by Hamas into believing Abu Sisi knew key information about Shalit’s whereabouts, it stands to reason it would not want such a failure known to the world. Israel’s security apparatus prefers the world to see it as fearsome and superb in its technical facility and operational execution. This case does not put the Mossad’s best foot forward. The best way to conceal this fashlah (“botched job”) is to put Abu Sisi away for a very long time and arrange so that no one inside Israel can tell the real story.

Abu Sisi’s engineering skills attracted Hamas’ attention

Dirar Abu Sisi met his wife, Veronika, in Ukraine, where he had earned a PhD in electrical engineering from a Ukrainian technical college in the 1990s. After completing his studies, they left for Jordan, where his family lived as refugees. He spent three months attempting to secure work as an engineer there. In 1999, he saw a job posting for a position at the Gaza power station. He applied, was interviewed and accepted for the job.

The salary he earned enabled him to support his growing family (eventually, he and his wife would have six children) and his elderly parents, who were living in a Jordanian refugee camp. He was the sole member of his family able to help his parents in this fashion.

He did his job well. He discovered that he could reconfigure the power station’s solar technology so that instead of using the Israeli power grid, he could use the Egyptian system. This saved the Gaza power authority over $200 million a year, but it did little to endear him in the eyes of the Israelis, who preferred everything in Gaza to be dependent on Israel.

Among the charges raised against the engineer by the Shabak, were that he studied at a Ukrainian military engineering program while earning his PhD. Already at that early juncture, the Israelis claimed, he was a dedicated Hamas operative seeking to learn skills that could be useful to the Islamic movement.

Prior to 2000, Abu Sisi had never visited Gaza in his life. In the 1990s, he traveled directly from Jordan, where he lived, to the Ukraine to pursue his PhD. When he completed his studies, he did not travel directly to Gaza. Instead, he went back to his home in Jordan. This offers further proof that Gaza was a professional destination, not an ideological one.

Regarding the claim of special expertise in missile technology: anyone with an engineering background can confirm that rocketry (i.e. aeronautical engineering) has almost no overlap with electrical engineering. So the idea that Abu Sisi could be the mastermind behind Hamas’ entire rocket program is far-fetched.

That being said, it’s only natural that a guerilla movement like Hamas, seeking to improve its weapons technology, would turn to anyone with any technical skills who could consult on questions related to these matters. So it’s quite conceivable that Hamas drafted Abu Sisi into service. Living under Hamas rule in Gaza, residents would have little choice but to comply with such a command. In fact, Linoy told MintPress that during a period when Abu Sisi was being less than cooperative with Hamas, its representatives threatened him, warning: “A man who has children as you do should be frightened for them.”

Abu Sisi’s resistance persisted. Linoy said that between 2000, when he arrived in Gaza, and 2010, his client attempted to flee Gaza no fewer than four times. The first attempt was in 2006, after Hamas staged an uprising which resulted in its takeover of the enclave. The resulting instability convinced Abu Sisi that he and his family had no future there.

He repeatedly applied for visas and appealed to various governments and U.N. bodies for help in emigrating. He reached out to the Israelis, the Jordanians (he was born in a Jordanian refugee camp), the Palestinian Authority, and the United Nations. Once, he even went on hajj to Saudi Arabia, hoping he could remain there with a brother who lived in the kingdom. But the Saudis sent him home. He finally did obtain a passport from the PA, thanks to the intercession of journalists and NGO officials he’d met through his work at the power plant.

After his third attempt, he was arrested and imprisoned by Hamas for six days. They accused him of being an agent for the Israelis, referring to his attempts to gain the latter’s assistance to leave Gaza. Linoy said Abu Sisi told him he was tortured by Hamas during this detention. But by then, he had received a PA travel document and his jailers realized they could not prevent him from leaving.

Two weeks after his release, he made his fourth attempt to flee Gaza. He escaped to Egypt, then made his way to Jordan, where his father lived in a Palestinian refugee camp (both men are stateless).

Jordanian intelligence colluded with Mossad in Abu Sisi’s detention

When he arrived in Amman, Dirar Abu Sisi was arrested by Jordanian intelligence agents, who had presumably been alerted to Abu Sisi’s presence by the Mossad. Given the extremely close security coordination between Israel and Jordan, it’s also possible the Jordanians alerted the Mossad to the Gaza engineer’s presence. But, as an Arab frontline state, Jordan would not give Abu Sisi directly to the Israelis for fear of being seen as overly cooperative with the “Jewish state.” That’s likely why Jordan permitted him to fly to Ukraine.

But when he finally boarded his flight to Kiev, he was accompanied by Jordanian security agents who ensured he arrived there, Abu Sisi’s brother, Yousef, told MintPress.

One of the first things Dirar Abu Sisi did on his arrival was to apply with the Ukrainian authorities for refugee status, to which he was entitled given his marriage to a Ukrainian citizen. One of the many excruciating cruelties of his case is that Ukraine eventually did grant him such status. But by then Ukrainian security agents had already betrayed him to the Mossad, and he was in an Israeli prison.

After applying for asylum, Abu Sisi planned for a reunion with his brother, an accountant living in Belgium, whom Dirar hadn’t seen in 15 years. The train ride was supposed to end with that long-sought reunion. Instead, when the train arrived, Dirar wasn’t on it. So began the mystery of his disappearance and reappearance ten days later in an Israeli prison.

A small item in a Ukrainian newspaper reporting the disappearance of a Palestinian there caught the attention of an Israeli source who, with the help of the Israeli human rights NGO HaMoked, helped me trace Dirar Abu Sisi to Israel. Despite a gag order and military censorship, my source was able to confirm the prisoner’s name and some details about what had happened. That enabled me to first report his kidnapping by Israel.

Abu Sisi punished by two-and-a-half years of solitary confinement

Dirar Abu Sisi was interrogated by the Shabak for ten days after he arrived in Israel. He had no lawyer, his family did not know where he was. In fact, his wife left Gaza and flew to Ukraine to try to find him.

Then, he was placed in the general prison population. He was moved to solitary confinement a week later, where he remained for two-and-a-half years. When his attorney, Tal Linoy, repeatedly objected to this draconian measure, he was told this was necessary because his client posed a great danger to the state. Linoy asked his jailers: “If Abu Sisi is a rocket engineer, as you claim, how can he endanger Israel sitting in a prison cell? Will he teach classes to inmates on how to make a better Qassam?”

The Shabak demanded his solitary confinement be extended for another six months on four separate occasions. Four times, judges agreed. Finally, Abu Sisi faced a personal crisis and great depression. If Abu Sisi didn’t do something he might never see another fellow inmate or receive a visit from his family again. He adopted a tactic used by other Palestinian prisoners protesting their treatment: He went on a hunger strike.

For 12 days he refused to eat. Keep in mind, this is a man with very serious health issues, including heart disease, high blood pressure, circulatory problems, anemia, asthma, severe back pain and gallstones, which were poorly treated by prison authorities. During incarceration he lost one-third of his body weight. By the twelfth day, the Israelis understood he was serious and relented. Abu Sisi was removed from solitary confinement and returned to the general prison population.

But the Shabak had more tricks up its sleeve: It transferred Abu Sisi from Beersheba, a 90-minute drive from his lawyer’s Tel Aviv office, to Mizpeh Ramon, the farthest southern prison in Israel. It is a three-hour drive from Tel Aviv. Now, instead of several meetings a week, Linoy could only manage one. It was yet another way to infringe on the prisoner’s right to counsel and bring frustration to the prisoner, his family and his attorney.

The security services exercise their tyranny in another important way: Instead of meeting with his attorney face-to-face as other prisoners do, they insist on a glass partition separating the two. This means that Linoy may not physically share legal documents with his client. Without being able to see and study such materials, Abu Sisi may not participate fully and effectively in building his legal defense.

To further elaborate on the Kafkaesque nature of the legal process, no one involved in the pleadings was permitted to mention “Ukraine” for fear it would damage Israel’s foreign relations (despite the fact that the case was widely reported both there and around the world). Nor could the defense refer to any of the agents who kidnapped him by name. Nor could he describe them. This is not an independent judiciary, but rather one held captive willingly by the security apparatus.

Further, the state has refused any family visits for Abu Sisi. He has not seen his wife or any of his six children for over four years. When Linoy offered to accompany his client’s children alone for a prison visit, the authorities refused. Speaking to MintPress, he joked mordantly that apparently they believe he will teach his rocket-making skills to his children. The authorities have similarly rejected every humanitarian gesture. He may only receive visits from his attorney and the International Red Cross.

No bargain

For years, the prosecution dangled a plea bargain before Dirar Abu Sisi: He could admit guilt and accept a sentence of 20-25 years. For years, he rejected the offer. In fact, very few security prisoners have held out that long. But, ultimately, no one goes to trial because no one wins at trial in these matters. The deck is stacked. The state always wins.

Accused prisoners face the choice of accepting a plea deal involving years in prison or going to trial and getting decades or a life term — that is, if the authorities try them at all. They don’t have to. They can keep them in prison as long as they like without trial. Abu Sisi stayed in prison for four years and never was tried.

Tal Linoy, Abu Sisi’s lawyer, says that throughout almost the entire legal process the judges were overtly hostile to his client. Every ruling went against him. The judges, he says, also took it personally that Abu Sisi made extra work for them by resisting the inevitable plea deal. It became clear to his lawyer that though he denied committing the crimes with which he was charged, if he didn’t agree to plead guilty, his sentence would likely be far longer than what was being offered.

When Abu Sisi finally agreed to a deal, Linoy argued that it should be less than the 21 years offered by the state. Linoy brought Prof. Robert Schmucker, one of the world’s leading experts on missile technologies in third-world guerilla conflicts, to argue that Abu Sisi offered limited, if any, assistance to Hamas.

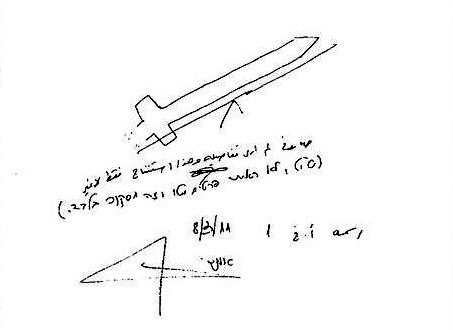

In his expert opinion: “The quality of knowledge [of Abu Sisi] seems very low, the mentioned activities very amateurish. … It is doubtful if his contributions had any effect … .” The drawing featured here is one Abu Sisi drew for his Shabak interrogators, illustrating that either he’s a terrible draftsman or knows as much about rockets as Gary Trudeau.

He also asserted during his “confession” that he amassed much of his “knowledge” about rockets from the Internet, even from YouTube. He had to learn it that way, because he had virtually no direct knowledge himself. As Ynet reported in 2011, he told interrogators:

“I don’t know anything about explosives. I would calculate pressure and heat using the Bernoulli Principle. I downloaded the formula from the internet. Not from any specific website. I did an Internet search and found it…I copied it down in an Excel folder and transcribed the numbers and calculated according to the formula.”

Bernoulli’s Principle has nothing to do with explosives nor does it have anything to do with “heat.” It is related to principles of flight. It’s also highly doubtful that a true rocket engineer would use Excel to calculate factors of lift for a rocket.

Linoy also reminded the judicial panel that the Abu Sisi family home in Gaza was destroyed during Operation Protective Edge, last summer’s war on Gaza. His wife and six children were made homeless. To this day, they move from home to home living temporarily with families who will take them in. They survive on a stipend offered to all Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails by the PA Ministry of Prisoner Affairs. This deserved some consideration from the judges, he argued.

Of the three judges he faced, Linoy noted that one had served as the IDF’s chief military judge. The second was an Orthodox Jew, which usually indicates right-wing political preferences. This majority ensured the will of the security apparatus would be upheld. The panel rejected Linoy’s arguments. Abu Sisi will serve 21 years. He will serve his full term, since there is no parole in security cases.

Abu Sisi will not see his children until they are grown adults and married with children of their own. And he will serve his sentence in one of Israel’s most remote prisons, hours from his family in Gaza.

His lawyer believes his case serves the interests, in a bizarre way, of both Hamas and Israel. Hamas’ rockets are a thorn in Israel’s side and cause major alarm when loosed on southern Israel. By arresting an alleged prime mover behind the rocket program, Prime Minister Netanyahu can claim a major victory against this menace. Of course, arresting one man, even a purportedly crucial man, won’t obliterate the threat. But the prime minister’s message to the population isn’t meant to be true or accurate, just convincing, at least in the short term. By the time the Israeli voter finds out that Abu Sisi’s arrest didn’t change a thing, he will likely have forgotten Abu Sisi even existed.

For Hamas, Abu Sisi’s arrest serves one primary purpose. The truth about its rocket program is that it is pathetic. Prof. Schmucker says Hamas cannot build any rockets within Gaza with a range of more than 8 miles. Any rocket it fires with a longer range has to be smuggled from elsewhere. In other words, Hamas cannot make sophisticated rockets of the type Israel claims Abu Sisi made. It can assemble the various parts of longer-range missiles produced elsewhere — say, Iran, for example. But to do this it wouldn’t need Abu Sisi, since assembly is a fairly straightforward proposition, especially compared to manufacturing from scratch.

Still, Hamas can argue, based on Israeli claims, that it has a magnificent rocket-production program home-grown inside Gaza. It can argue that the Palestinian resistance has the capacity to attack the Israeli heartland thanks to the native brilliance of rocket engineers affiliated with Hamas.

Abu Sisi excluded from two prisoner swaps

There have been two major prisoner exchanges between Israel and the Palestinians since Dirar Abu Sisi’s arrest. He has been included in neither. The Israelis claimed at the time that only prisoners who’d been tried for their crimes were eligible for release. When Abu Sisi’s wife approached the Ministry of Prisoner Affairs to ask why Hamas didn’t lobby for Abu Sisi’s inclusion in an exchange, they claimed the lists were prepared by the Israelis.

After the first such exchange, I contacted Gershon Baskin, the Israeli interlocutor who negotiated the deal with Hamas. I asked if he would inquire of Hamas on Abu Sisi’s behalf. Baskin never replied.

Abu Sisi has no nationality, no political party, no friends, no allies. He is neither Fatah nor Hamas. No one is looking out for a person with no allegiances, either inside or outside the prison. The Shabak is fully aware of this and exploits it. It knows it can abuse such a prisoner at will and that no one will raise a voice or lift a hand to help.

There is talk that German officials are mediating negotiations on a third prisoner exchange with Hamas. It would bring home the remains of two IDF soldiers killed in last summer’s war and two live Israelis who strayed into Gaza during the past year. Abu Sisi will not be among the Palestinian prisoners released.

The only thing that might change this is publicity, giving Israel a black-eye in the foreign media for its mistreatment of this man. If the story is told enough, if enough damage is done to Israel’s image, it may evoke some flexibility and a more favorable response.

After reading my original Truthout story about the case, Gabriel Gatehouse took it up and produced a 30-minute BBC documentary. He traveled to the Ukraine, Gaza and Israel and interviewed all the key figures in the case. More such coverage might change Abu Sisi’s fate.

Listen the BBC audio documentary about the Abu Sisi case based on Richard Silverstein’s reporting: