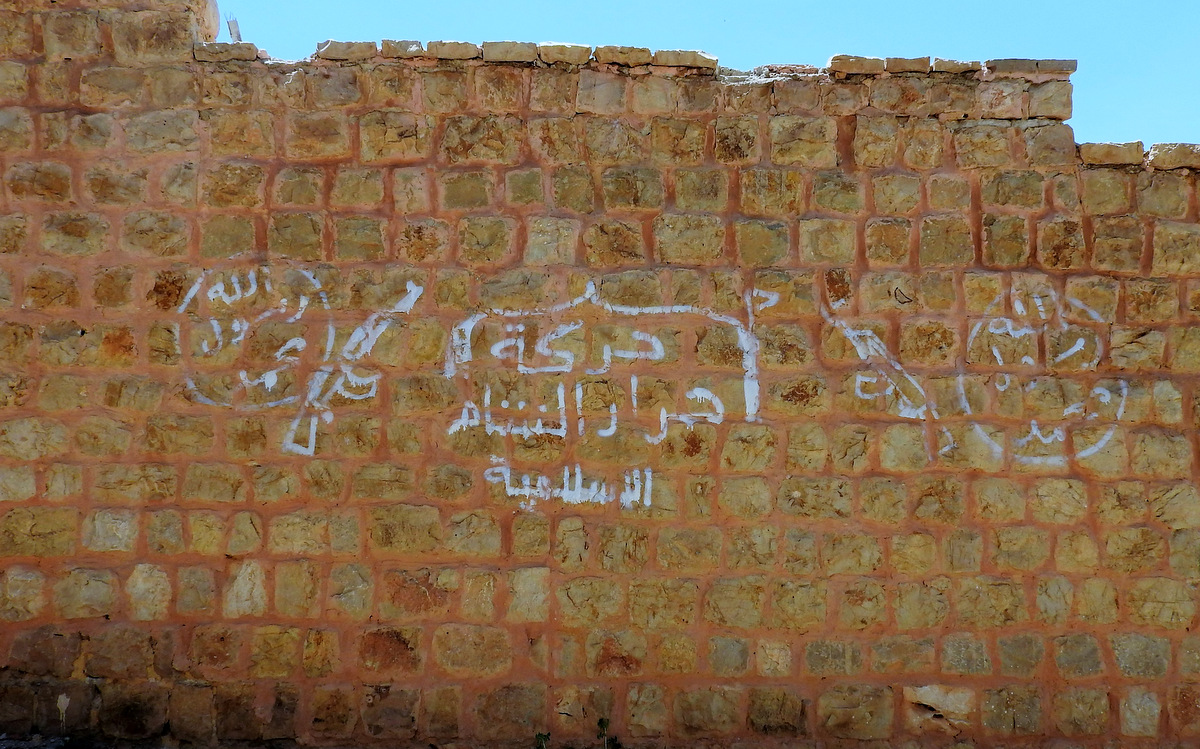

HOMS, SYRIA — In the last year, the Syrian cities of Aleppo and Madaya have become familiar to the international community as they have become subjects of heavy propaganda amid corporate media coverage to justify a so-called “humanitarian” war. Another area used in the war propaganda was al-Waer, a district of Homs occupied by the Western armed and financed “moderates” of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), al-Nusra (al-Qaeda in Syria), Ahrar al-Sham, and terrorists showing allegiance to Daesh (ISIS).

When I again visited Syria in June 2017, Aleppo, Madaya and al-Waer had been restored to peace, following the evacuation of these armed groups. I was able to visit these areas and speak to residents about the reality of life under the rule of these factions

In Part I of my coverage August 2017 article focused on Aleppo and the life of civilians there under “rebel” occupation — which included many dangers, deprivations, and horrors, not the least of which was susceptibility to extra-judicial trials and executions.

Here, I look at Madaya and al-Waer, again from on the ground, to give a voice to Syrians who have been marginalized by the Western corporate media, which has instead glorified the insurgency.

Stability with reconciliations

During my visit in June, I met with Syria’s Minister of Reconciliation, Dr. Ali Haidar. Established in June 2012, the Ministry has successfully dialogued with tens of thousands of armed Syrians to enable and facilitate return to their civilian lives.

According to Haidar, in Madaya and al-Waer stockpiles of food and medicines were found in buildings occupied by armed groups. Large quantities of weapons and ammunition were also found—notably foreign-made weapons—including from the U.S. and Israel. While Western media has not reported on this, Israel’s JPost in April 2016 reported on another incident: the capture of a vehicle containing Israeli mines coming from southern Syria.

Haidar explained to me that an agreement was reached at the end of 2015 that included Madaya, nearby Zabadani, and the Idlib villages Foua and Kafraya. That 2015 agreement saw over 450 people from the four areas evacuated by agencies, including the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

The evacuated included injured, ill and elderly from Foua and Kafraya, with some of whom I met in August 2016 to hear about their experiences.

According to a report compiled in the Reconciliation Ministry, and explained to me in our June meeting, 3,000 people, including 950 militants, left Madaya for Jarablus or Idlib on April 15, 2017. Another 600 militants laid down their arms on April 19, staying in Madaya. As of June, 20,000 people had returned to Madaya.

In a June 2014 interview, Minister Haidar told me that over 10,000 Syrians had reconciled and returned to their civilian lives. According to his office, as of June 2017, that number was over 85,000.

Media explosion on Madaya

Adjacent to a munitions factory used by armed groups in Madaya, I found packaging of an ICRC-supported food parcel, a remnant of repeated aid convoys sent into the town. As in eastern Aleppo, in Madaya armed extremists hoarded food and medicines.

Owing to the presence of Ahrar al-Sham, al-Nusra and other groups, from around mid-2015 Madaya was under Syrian military siege. As noted in Part One of this series, siege is a common tactic of wars past, and one that the United States employed in Iraq (for example, the more than four-year siege of Sadr City).

The military sieges came with offers of amnesty to those armed Syrian men who hadn’t committed bloodshed, or safe passage to another area of Syria for those who refused reconciliation, including the non-Syrian extremists. During the siege, the Syrian government did continue to send in aid to Madaya, and continued to also approve the provision of aid from the ICRC, UN and other bodies, including in October 2015.

In December 2015, the ICRC was back in Madaya for the evacuation of injured or ill.

In his January 2016 statement, Syria’s permanent representative to the UN, Ambassador Bashar al-Ja’afari, confirmed this October 2015 aid delivery, and noted:

“On December 27th, we asked the resident coordinator to send immediately convoys of humanitarian assistance again to Madaya, and to Kafraya and al-Foua. The UN did not send. … Huge humanitarian assistance and medical assistance was distributed inside Madaya, October, December and now (January).

The main problem is that the armed terrorist groups steal the convoys and trucks, and they deviate them to their own warehouses and storage. And then they resell it to civilians at prohibitive prices that the civilians cannot afford it.”

Overnight in January 2016, Western and Gulf media, in chorus, started campaigning that the Syrian state was starving civilians in Madaya. The same media made scant to no remarks about the terrorists occupying the hillside town. Some reports used photographs of emaciated people not from Madaya, nor even from Syria — including a pretty Lebanese girl whose parents objected to the media’s exploitation of their daughter — in support of the “starvation” claims.

Watch | ‘Fact Check on Madaya’

Those behind the sudden media upheaval included none other than Saudi terrorist Abdullah Muhaysini, known for his support to al-Qaeda and recruiting of new terrorists. In early January 2016 he also called for the annihilation of Foua and Kafraya.

A cached article noted that Muhaysini had “appealed to the media to highlight the disaster in the region.” Another article, in Arabic, cited Muhaysini as using the hashtagged phrase “Madaya is Hungry”.

When, in mid-january 2016, Syrian reporters and RT reporter Murad Gazdiev entered Madaya with another shipment of aid, residents spoke of the starvation caused by the terrorist occupiers, as residents of eastern Aleppo and al-Waer later would: The terrorists stole the food aid and sold it at prices too obscenely inflated for civilians to afford.

Watch | Inside Besieged Madaya: ‘Militants sold us 1 kg of rice for $250’

On the ground in Madaya, June 2017

There was normal life on the streets of Madaya when I visited last June. Small grocery stores and other shops were open, residents and children filled bottles at the central water fountain. A sense of calm prevailed, with Ahrar al-Sham and al-Qaeda two-months departed.

Entering a small shop selling clothing, I was welcomed and offered apricots from a pail on the counter. The Madaya-Zabadani region is known for its rich agriculture and tasty fruits. It is also an area to which people from Damascus and environs would retreat in the summer, to picnic on farmland or to eat at one of the restaurants along the road leading to the towns.

According to Madaya’s mayor (mukhtar, in Arabic), the main armed factions that had been present were the terrorist groups of Ahrar al-Sham, al-Nusra and the FSA. The shop owners also maintained that ISIS terrorists had been present in Madaya.

I asked if they had seen ISIS themselves. Their reply: “ISIS killed a civilian outside the shop.” As it turned out, when the man was shot, residents were protesting the presence of ISIS in the town.

I asked whether people had protested the presence of other militants. “Yes,” they said, “there were protests against the armed groups, and in support of the government, asking the government to come to Madaya. ISIS killed three protesters and another seven were injured.” Indeed, I had seen a video of Madaya residents marching in support of the Syrian president and against the armed factions.

To my question whether Western media was right, that the Syrian government had starved them, the four men answered ‘no’ in unison, talking over one another to make their point.

“It was not the government that starved us, it was the armed groups,” a middle-aged man said.

“The government provided us in Madaya with supplies that would have been enough for 20 years,” a younger man exaggerated, making the point there was ample food in the town. “We received aid convoys, but the armed groups would steal the supplies and monopolize them.”

He said he had sold his car in order to buy overpriced food from Ahrar al-Sham and al-Qaeda: “They sold us a kilogram of rice for 100,000 Syrian pounds.”

At current exchange rates, this came to around US$200.

An older man nicknamed Abu Sharif said repeatedly that militants had hoarded food and extorted civilians, and added:

“After the Syrian army entered, they found 50 storage units of food, also medicine. They are still uncovering storages.” According to this man, the militants also stole jewelry from women, and forced them to dress fully covered. “They called us ‘kuffars’ and said we weren’t real Muslims.”

The mukhtar maintained: “The siege from the Syrian army had the effect that the terrorists started surrendering themselves at Syrian army posts.” Indeed, SANA reported in June 2015 that 11 armed men had turned themselves in and — even prior to the siege, in August 2014 — over 250 militants had joined the reconciliation process:

“The siege was on the militants, if they hadn’t been here, there would have been no siege. There’s no siege now, everything is open.”

Prisons, civilian shields, and a bomb factory

With the mayor, two villagers, and my driver/translator, we drove from the town hub and along winding roads leading to an area of attractive apartment homes at the edge of the town.

Stopping the car en route, the mayor pointed at a small school, one of six in the town. A few stories high, its walls had been blown out, presumably by Syrian army shelling. “It’s an elementary school. The militants occupied it and took it as a stronghold and fired from it,” he said, saying that terrorists had occupied all of the town’s schools.

In his investigations, Aleppo journalist Khaled Iskef highlighted why armed groups had occupied schools. According to a former fighter for the Shami Front whom Iskef interviewed, “Terrorists use schools because the infrastructure is solid and they have cellars to use for munitions storage and prisons.”

Madaya never had a hospital, only a small clinic, which the locals said terrorists had closed to the public. The regional hospital for the area is in nearby Zabadani. Yet, by November 2016, reports on Madaya’s nonexistent hospital includedd this headline from the Qatar-funded Middle East Eye: “As Madaya’s last hospital closes…”

This is the same ‘last hospital’ theme that abounded in propaganda around Aleppo.

The town did have a small medical clinic, though. In the media spin around Madaya, purportedly heroic non-MDs were treating the citizens of Madaya, including one dentist and one veterinarian.

According to the mayor and other men I spoke with, though, only terrorists and their families were treated or given access to medicines. Given that this accusation was later widely heard from civilians in liberated areas of Aleppo, and given that the terrorists in question were al-Qaeda and Ahrar al-Sham (which the U.S. Congress lists as a terrorist group in its own documents), it is highly unlikely that the Madaya people who alleged this were not telling the truth.

Madaya’s mayor said he knew the two “hero doctors.” Of the dentist, the mayor said he benefited from helping the militants. “He could get whatever he want[ed] from them, like food and medicine, and he became famous in the media.”

The video on this hero doctor was Netherlands-produced (a country which supports the ‘opposition’), and featured a Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) board member. SAMS purports to be a “nonpolitical, nonprofit, professional and medical relief organization,” but supports al-Qaeda-occupied areas in Syria. Their own website notes meetings with the State Department, Homeland Security, and other establishment policymakers, including U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Samantha Power, former President Barack Obama and former Secretary of State John Kerry — all deeply involved in the U.S. war on Syria.

In addition to occupying schools, “moderate rebels” occupied apartment buildings and the luxurious villas, turning some into prisons. Standing next one apartment, the men told me that it and buildings across the road were used by the occupiers to bomb and snipe the Madaya-Zabadani road below:

“The civilians living below were like human shields for the terrorists. The army couldn’t shoot at the terrorists easily because they’d risk hitting the civilians.”

I asked how life was in Madaya before 2011. “Madaya was a tourist’s paradise,” the mayor replied, smiling, eyes closed, remembering. “People who came from outside of Syria would come to Madaya,” to enjoy the environment of natural beauty.

Further on among the hillside dwellings, we stood near an apartment that had been occupied, one floor turned into a prison to hold locals until their fates (including execution) were decided in terrorists’ Sharia trials.

Nestled behind the apartment, out of view, was a factory where terrorists manufactured mortars and rockets.

Watch | Hidden factory where mortars and rockets were manufactured by terrorists

Above that factory, one of the food storage caches was found after militants had left Madaya. The mayor said, “Last time the army found a storage with more than 400 cartons of food.” Syrian authorities filled five trucks with medicine hoarded by the armed groups, he said.

Walking gingerly over rubble, not yet cleared by engineers of any unexploded ordinance, we reached the bomb workshop, a single ground-level room. Equipment and materials for manufacturing explosives still lay scattered.

Down the lane, another villa had also been used as a headquarters and prison until it was hit by Syrian army shelling, forcing the “rebels” to relocate. Another mass food storage was found in a neighboring building, the mayor said.

Entering the relocated prison through a hole blown into the wall, I walked past a room containing a cooking stove and refrigerator, both booby-trapped by terrorists to kill whoever tried to move them. I had learned of this tactic in 2014 in the old city of Homs.

Watch | Our visit to the relocated prison

“They left booby-trapped explosives in the houses, all over, even behind paintings on the wall,” I was told. Similarly, in Maaloula in June 2016, I was told: “They rigged houses so that when someone opened the door, an electrical trigger with a small charge would detonate and explode a gas canister.”

Two rooms, metal doors welded onto the entrances, had been used as cells. In the middle of another room, a metal bed frame with a piece of cloth tethered at one end. “They interrogated and tortured people here,” a former FSA militant said. An unwilling participant, he said he was forced by other militants to join, and that he was among the first to take the government-offered amnesty when peace was restored to Madaya in May 2017.

In neighboring Buqayn, Ahrar al-Sham transformed the municipality building into a prison, fortified with sandbagging and bricks. The dank cells were sealed with the same solid metal doors.

A soft-spoken employee of the municipality, limping as he walked, came over to tell me how he was shot at close range. Leaning on a crutch with prayer beads wrapped around the handle, he explained his injury. Recounting that terrorists had shot at the truck he and three others were in, he said, “the driver was killed and we were all injured. … We were subject to shooting many times.”

Watch | Municipal employee describes being shot by terrorists as part of intimidation campaign

The reason for the attacks? To intimidate them from returning to work at the municipality. Three surgeries later, still needing another, the man said his wounded leg is now seven centimeters shorter than his good leg.

Below and beyond the village, in a sitting room away from the June sun, a farmer-turned-soldier, still wearing his military uniform, spoke of why he took up arms in support of the Syrian army:

Life was good here, we were living well. When things turned violent in the area, I and other men from the area volunteered to support the Syrian army.”

He and others warned Madaya locals not to fall for the political game that originated from America, Israel, Turkey and others, he said — also pointing out that sectarianism was never a way for most Syrians, that it came from Saudi Arabia and other outside forces:

If you came and visited our home, slept in our home, we never asked what religion you were.”

As I left, he insisted on giving me bags filled with cherries and other fruits grown on his land.

Al-Waer at peace

To the west of Homs lies the suburb of al-Waer. In December 2015, when a truce was holding, I had stood at a Syrian army checkpoint on the western outskirts of al-Waer, speaking with residents as they crossed back into the district with food from outside and bags of bread from the industrial-sized bakery to the side of the road.

Trucks loaded with eggs, meat and medicines waited to enter the district. Zakariya Sha’ar, a doctor bringing medicine, mentioned the presence of non-Syrian militants, including Saudis, Tunisians, and Chechens, among others.

As I stood on the road, less than 100 meters from the checkpoint of the militants, I was cautioned to step back: “It’s not safe, at any moment they could do anything, break the ceasefire.”

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=1109530025723657&set=a.1128530780490248.1073741883.100000000104830&type=3&theater

Inside the bakery, I saw locals producing the bread that would go into al-Waer. I was told the wheat was provided by the Syrian government.

Watch | Footage inside the al-Waer Bread Factory, Homs

Syrian Minister Ali Haidar told me that armed groups had gathered in al-Waer due to its large population, around 300,000 people:

They [the armed groups] entered al-Waer, closed it off, and turned it into a zone to fight the government. The large number of civilians made the government unable to start a direct battle against the militants. Therefore, we remained around the neighborhood.”

According to Haidar, the Ministry started attempts at broaching reconciliation at the end of 2013, and reached an agreement at the beginning of 2014:

However, the large number of the militant groups in al-Waer, the internal disputes among them—and most importantly the control of al-Nusra over other militant groups—hindered the project after we had begun.”

The reconciliation effort began anew early 2016 but, again due to the presence of al-Qaeda, was delayed for a year — hampered by “external directives, mainly Qatari, to leaders of militant groups to hinder the project,” Haidar said, “[in order] to cause problems outside al-Waer.”

When from March to May 2017 the evacuations did finally occur, no UN personnel were involved, Haidar said, only the Syrian Red Crescent, Russian military police, and Syrian security personnel. As with evacuations elsewhere in Syria, militants left with light arms.

According to a detailed breakdown (provided to me at the Ministry of Reconciliation) of the 11 evacuations from March 18 to May 21, the final tally of militants who departed from al-Waer was 4,937, with a further 750 who chose to reconcile and stay in the district. Of the departed militants and their families, Minister Haidar maintained that at least 70 percent were not from al-Waer but from other areas of Homs and elsewhere.

“Immediately,” Minister Haidar told me, “we started the plan to return the locals to al-Waer.” As of June, there was a plan for the return of 50,000 people to al-Waer over the next couple of months.

Visiting secured al-Waer

In a local taxi, I approached the district with a journalist from Homs. Driving along smooth boulevards, Hayat and the driver took turns telling me about al-Waer, nicknamed “New Homs.” It was known for the green spaces and parks, the good infrastructure, she said — and impeccable infrastructure, the driver interrupted, saying “life was so good here.”

As the taxi entered al-Waer, a housing complex came into view, and apartment buildings further along, all studded with gunfire and holes from shelling. The car paused in front of a building where a boy of perhaps 12 years shoveled rubble from in front of his home. The buildings to the left of him were blackened from shelling.

Some minutes later, we passed an empty lot with shells of buses pocked with gunfire. Further along, another bus, windows blown out, was parked across a road formerly leading to a Syrian army checkpoint. Walking along the streets, Hayat pointed to an intact multi-story apartment building, and another with shelled upper-level rooms.

“This building had civilians. That building had militants,” she said, indicating that buildings not used by militants were not targeted.

This is a difference many journalists willfully overlook, choosing instead to speak of physical destruction in general terms, ignoring and negating the presence of terrorists — whether high up in sniping and shelling vantage points, or bunkered safely below ground, as I saw in Bani Zeid, Aleppo last year — and the efforts made to confine destruction to these targets.

A green bus filled with passengers passed by, characteristic of those used in the evacuations in eastern Aleppo. They were also used in al-Waer, along with other buses, for the evacuation process. Today, as in Aleppo, the buses are back to city services. There was some life on the streets otherwise: an older man bicycled down one lane, and a child crossed the other in the distance.

In one small shop, a young clerk was reluctant to talk about life under terrorist rule, as was his father. Possibly the family supported the militants.

Another shop, unfurnished save for a faded plastic poster of a horse and another of a mother and child, was stocked with items that had been long-absent for most people. Sugar, flour, detergents, eggs, a variety of cigarettes, an array of chocolate bars and cookies, and bags of potato chips, instant noodles, and other non-perishable food items filled the shelves.

The shop owner said they had suffered from hunger. “The armed groups wouldn’t give us anything at all,” he said. “The opportunists, you mean,” remarked an older man, a friend, who had walked in. The latter continued: “One kilogram of salt reached 8,000 Syrian pounds (US $16), one bag of bread 3,000 pounds (US $6).”

I asked about the bakery I had seen in 2015, and whether bread in fact regularly entered the district. “Yes,” said the second man, “it did,” but the militants would sell it at the inflated prices he had mentioned.

A man selling cigarettes on a street corner, his makeshift table stacked with cigarette cartons, said he hadn’t left al-Waer during the presence of the militants — it was and is his home.

“Life was very, very bad. There was no food, they used to take the food for themselves,” he said of the armed groups, continuing with the same complaints as the others I’d spoken with: “They would sell it to us with a price they decided,” he said, citing similar exorbitant prices for flour, sugar, and basics.

A father of six children, he worried about their future after so many years of war. We parted with his last words:

But now the army is here, they are doing good, hopefully everything will return back to how it was.”

Further on in the district, three men worked clearing rubble from around a home badly damaged on the ground level. They waved and greeted us as our taxi stopped, but went silent and refused to speak when noticing my camera. A level up, a woman’s face peered out a small hole in the wall, then her hand reached out and gestured to come upstairs.

She was one of the many who left al-Waer, departing in 2013 and renting elsewhere in Homs. She said her life prior to 2011 was wonderful, and was strongly optimistic for the future:

“People are coming back home. Although many houses are destroyed, they are inhabited. If they are destroyed, we’ll rebuild them. What matters is that we’ve got rid of those bastards,” she said of the militants dubbed “moderate rebels” by western media and politicians.

The men below, it turned out, had been militants, but took amnesty and reconciled with the state, and are returning to their lives.

This was hard for me to process: living in the same building is a family evidently patriotic—the woman’s brother is in the Syrian army and she herself praised both the army and government—and the very former militants the family fled from, men who took up guns against both the government and in many cases civilians.

I asked if she knew her neighbors well. “Of course,” she answered. “But some people were brainwashed by others about ‘bad people, oppressing people.’ So, there were guys who joined those bastards,” she said of the militants.

As we spoke, one of the men came into the room. We shifted the conversation to casual talk about her family. After he left the room, she explained quietly that he was keeping an eye on her, what she might be saying to me. I was again struck by the strangeness of the situation, and when he had left, asked her if she wasn’t afraid to be living above the men.

“The state is here, we aren’t afraid. They’ve provided everything for us, are helping us, mash’allah,” she replied.

I stopped on the stairs leading from her apartment, listening to the call to prayer coming from the nearby mosque, watching as life trickled along the streets of the badly damaged district.

Watch | Pausing to listen to the call to prayer from nearby mosque

The sounds of shoveling rubble below were both a reminder of the militants who had been a part of this destruction and of the fact that they too want to rebuild and get on with life.

Epilogue

When at the Ministry of Reconciliation later, waiting for my meeting with the Minister, I saw many women and some men also waiting to talk with someone at the Ministry, about their loved ones, militants who had left another restored district, Qudsaya, for Idlib in October 2016. The militants wanted to come home.

The minister’s office also told me at the time that 72 families had already returned to more-recently secured al-Waer, from Jarabulus.

On July 11, Syrian state media, SANA, reported: “Fourteen buses carrying about 150 families, including 630 persons from the residents of al-Waer neighborhood, have arrived in Homs city coming from Jarabulus.” The report noted that this was the fifth group of families returning from Jarabulus or Idlib, and that many more families were scheduled to return.

Top photo | Syrian children buy vegetables in the town of Madaya in the Damascus countryside, Syria, May 18, 2017. (AP/Hassan Ammar)