MEXICO CITY — Mexico appears to be on the cusp of massive change. Leftist presidential candidate Andres Manuel López Obrador has a very good shot at winning the upcoming election but the threat of fraud looms over the vote. This election has already been witness to political assassinations, vote buying, and voter intimidation.

For several months, law professor John Ackerman has been diligently working with a team of intellectuals and activists on an effort to prevent fraud in the upcoming election. He is very excited about the prospect of change in the country but minces no words: in his view, Mexico is not a democracy…yet. He told MintPress News:

We’re still in this process of struggling for democracy. The hope is that July 1, 2018 will actually be the beginning of a democratic transition, that finally someone really from the opposition with mass popular support will become president based on elections.”

Mexican democracy still waiting to be born

That point-of-view may come as a surprise to some: mainstream analysts point to the 2000 election as the birth of Mexican democracy. Previous to that election — in which they were unseated by the right-wing National Action Party, or PAN as it is known by its Spanish acronym — the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, through clientelistic networks and electoral fraud, ruled Mexico uninterrupted for 71 years.

“The simple fact that the so-called opposition won in 2000 doesn’t mean that Mexico is a democracy because … what we see is the continuity of the authoritarian system,” said Ackerman who added:

Really the idea that somehow in the year 2000 there was a qualitative change in the equilibrium in politics is a myth.”

Read more by José Luis Granados Ceja

- In Mexico, Resistance to Govt Collusion with Capitalists and Organized Crime Triggers Criminalization of Dissent

- As Drug War Casualties Mount, Mexicans Take to the Streets Demanding Answers

- From Brazil to Ecuador to US, Mexico’s Labor Unions Learn Lessons of Trusting “Progressive” Presidents

- The Indigenous Community that Rebelled Against Narcos, Thieves, and Politicians … and Won

The PAN ruled Mexico for 12 years, first under Vicente Fox and then under Felipe Calderon, the latter seen as responsible for unleashing a wave of violence throughout the country that continues unabated today. Expectations that a change in leadership would resolve the issues plaguing the country – violence, inequality, corruption, extreme poverty and stagnant wages – were largely dashed and in 2012 the country voted the PRI back into power.

However, in this current election, Lopez Obrador — the leftist former mayor of Mexico City, who is now running for a third time — commands an overwhelming lead, with some polls giving him as much as 20 points over his nearest rival, Ricardo Anaya, who is running for the PAN as part of a left-right coalition.

Mexico’s flawed institutions

Lopez Obrador’s victory would mark the end of nearly a century of rule by two neoliberal parties, the PRI and the PAN, and would also mark the first leftist government in Mexico’s modern history.

That is why many ultimately consider the 2018 vote as the country’s most important election in recent history.

But Mexico’s political elites do not intend to go quietly and are utilizing every trick in the book to try to affect the outcome and prevent AMLO, as Lopez Obrador is commonly known, from winning.

Despite AMLO’s massive lead in the polls, successful electoral fraud is entirely possible. Most elections in Mexico have been marred by allegations of fraud. Notable examples include the 1988 election when early results indicated the ruling PRI was set to lose until the computer system tabulating the result “went down” — when it returned, the PRI was leading comfortably. The 2006 election, AMLO’s first attempt, was also condemned as fraudulent and led to weeks of protests, though ultimately electoral authorities did not allow for a total recount of the votes and the fraud was consolidated, allowing his rival, Felipe Calderon, to take office.

Lopez Obrador’s critics accuse him of being a demagogue who turns his nose up at the country’s institutions. Yet he has consistently turned to those institutions, seeking power through elections, despite the glaring flaws in the country’s system.

Those flaws are well-known to many Mexicans. Ackerman, a U.S.-born Mexican national and law professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, helped put together Dialogues for Democracy, a university initiative that trained thousands in election-related issues.

These citizen advocates of democracy are not placing blind faith in the country’s institutions.

“These guys are capable of anything, the corruption of the Mexican system is so deep, the institutions are in such profound crisis,” argued Ackerman.

The issue is that the very state institutions that AMLO’s critics say he does not respect, have not won the respect of Mexicans.

As Ackerman told MintPress News,

The electoral institutions are supposedly autonomous but they are part of the same system of corruption and institutional weakness and so very few people trust the National Electoral Institute or the electoral tribunal or the special electoral prosecutor for electoral crimes; lots of mistrust based on a history of frauds and illegalities.”

Vote buying, voter intimidation, and political assassinations

This election has already been witness to a number of irregularities, the kind practiced in previous elections — such as vote-buying, the conditioning of social programs based on party affiliation, and voter intimidation.

As Ackerman observed:

The PRI continues to be a very powerful machine system and it’s not just any kind of voter mobilization; this is corruption, this is direct vote-buying, this is threatening people that they will lose their government supports or access to education and healthcare if they don’t vote for the ruling party.”

In a country with rampant poverty, these vote-buying tactics are very effective. A report from Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity found that the election was awash in so-called “dirty money” — that is, money that comes from dubious sources and is not reported to electoral authorities.

Ackerman says Mexico’s political elites have engaged in a “dirty war” against Lopez Obrador, pulling out all the stops to prevent his victory.

Ackerman says he and his team have documented websites that promote “fake news” against AMLO. Millions of Mexicans have also received phone calls that masquerade as polling firms but are in fact attack ads against Lopez Obrador. Rival parties have even sent provocateurs to campaign rallies to provoke fist fights with AMLO’s supporters, and this week armed individuals stole over 11,000 ballots.

These tactics are, of course, illegal but the institutions involved do little to try to stop them or even mitigate their impact.

The National Electoral Institute and the country’s electoral court, known as the TEPJF, have made a number of decisions that have called into question their impartiality. Since the members of these bodies are appointed by Congress, which is presently comprised of political forces opposed to Lopez Obrador, Ackerman argues all these institutions are biased against AMLO.

He highlights the case of Jaime Rodriguez, an “independent” candidate that is running a distant last. The TEPJF forced him onto the ballot despite his failure to meet the requirements to register as an independent candidate. Ackerman believes he was put on the ballot solely to play the role of attack dog against Lopez Obrador. And neither the National Electoral Institute or the TEPJF have done anything substantial to stop the illegal anti-AMLO phone calls.

The New York Times also recently revealed that the PRI approached the scandal-plagued Cambridge Analytica, the firm behind Facebook’s data scandal, to help them in their reelection efforts. Ultimately the PRI decided not to work with the firm but did, nonetheless, pay them off in order to ensure the firm would not work with any other campaign.

This election has also been particularly violent: over 100 politicians, including dozens of candidates, have been assassinated throughout the course of the campaign. Most recently, five supporters of Lopez Obrador’s party were ambushed and killed in the state of Oaxaca.

Mexico’s political elites are also not averse to outright vote manipulation. Although the elections are coordinated by the National Electoral Institute, the voting centers are staffed by citizens who are selected at random. In previous elections, such as state elections in 2017, these poll workers and observers were bought off or scared off by nefarious actors, allowing unscrupulous activities to take place inside the voting booth, including ballot box stuffing and manipulation of tally sheets.

“There will be attempt at fraud, we’re already seeing it. The scientific estimations say that in Mexico you can steal about 6 percent of the vote,” said Ackerman.

Stopping fraud in its tracks

But it is not just Mexico’s politicians that oppose AMLO, there are powerful economic interests that are afraid of a Lopez Obrador victory.

Ackerman noted:

There are people who have received millions of dollars and are corrupt, and who are very afraid that if there is a democratic transition in Mexico there might be an investigation into their cases, so they’re willing to do anything possible, by any means necessary, to stop Lopez Obrador.”

That is why activists, lawyers, and academics have started the University and Citizen’s Network for Democracy, which is working with hundreds of election observers, including over 60 international visitors, to observe Sunday’s vote.

The goal of the University and Citizen’s Network for Democracy is not to document fraud but rather actually to try to stop it. The recent alleged electoral fraud in Honduras proved to many in Mexico that international bodies like the Organization of American States, which is also sending an observation team to Mexico, are not capable of actually stopping fraud from happening or being ratified.

It is highly unlikely that Mexican society would be willing to swallow electoral fraud. With Lopez Obrador consistently running high in the polls, a result that does not reflect this trend would provoke mass social discontent. Ackerman believes that Mexico would be witness to a kind of political instability unseen in recent history.

Lopez Obrador has said that if the election is stolen, he would not try to contain the discontent (as he did after the 2006 election), which would prompt unpredictable consequences for Mexican society.

In other words, the stakes are incalculably high.

It is not clear if Mexico’s political and economic elites are willing to take that gamble.

However, Ackerman argues this election is different: in this case, the ruling class is divided and there are business elements supporting Lopez Obrador’s candidacy. He adds that in contrast to previous elections, other left-wing forces such as the Zapatistas are not actively promoting a null vote or voter abstention, as they previously have.

The conditions are in place for Lopez Obrador to make history on Sunday and for Mexico to mark a new democratic era.

“It’s not about Lopez Obrador, it’s about democracy — that’s what he’s been struggling for, and what the vast majority of the Mexican population want,” said Ackerman.

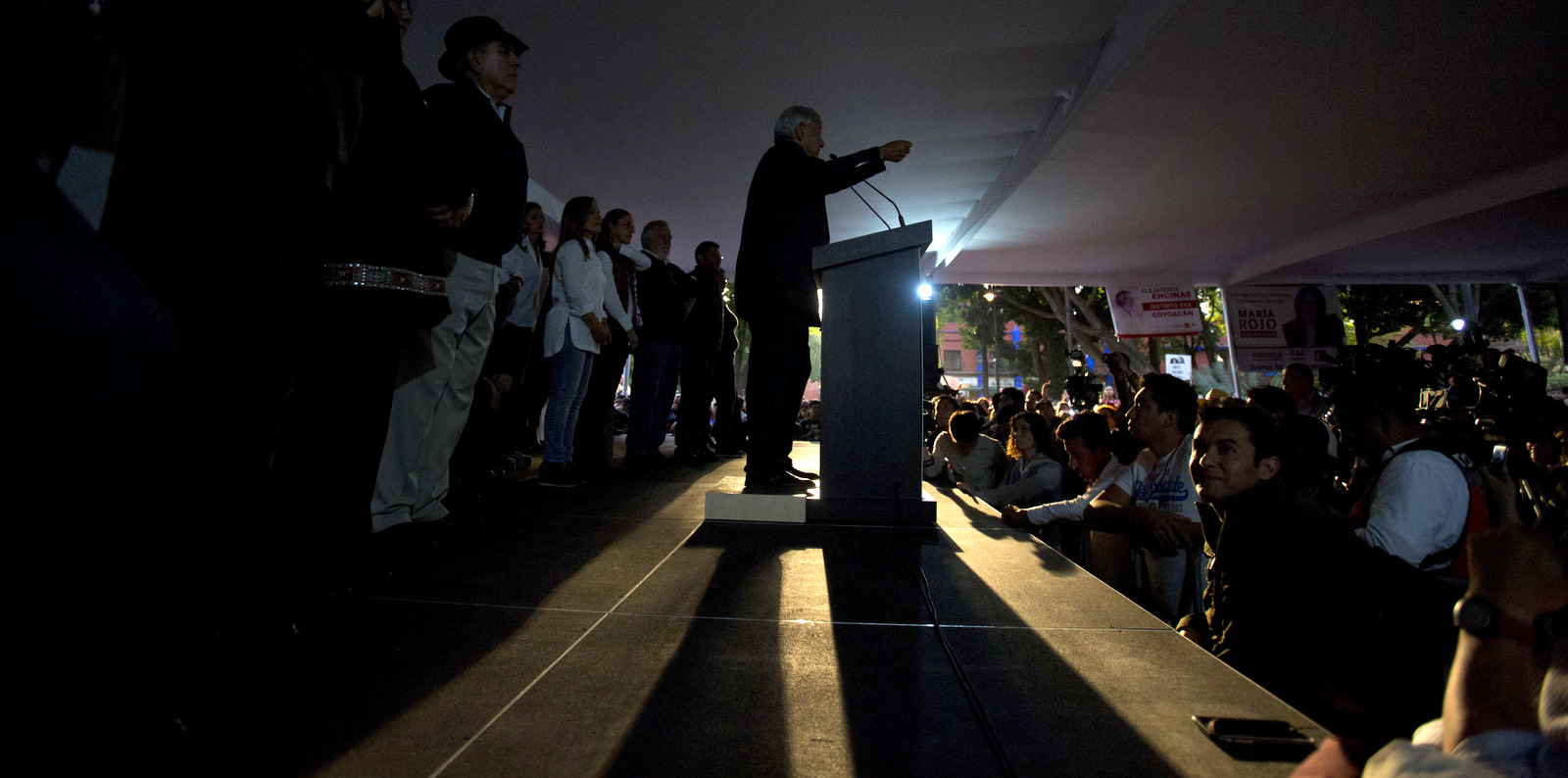

Top Photo | Presidential candidate Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador of the MORENA party speaks during a campaign rally in the Coyoacan district of Mexico City, May 7, 2018. Mexico will choose a new president in general elections on July 1. Rebecca Blackwell | AP

José Luis Granados Ceja is a writer and photojournalist based in Mexico City. He has previously written for outlets such as teleSUR and the Two Row Times and has also worked in radio as a host and producer. He specializes in contemporary political analysis and the role of media in influencing the public. He is particularly interested in covering the work of social movements and labor unions throughout Latin America.

Disclosure: John Ackerman is married to Irma Eréndira Sandoval, who has been proposed by Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador as his future Secretary for Public Service.