(CONNECTICUT) – Perhaps there was a time when the U.S. could have done what other rich countries did: provide universal health care through a nationalized single-payer system similar to our old-age insurance program, Medicare. But we didn’t, and there are at least two reasons why.

One is obvious. Our power elite, the titans of finance and industry, hated the idea. It was foreign. It was socialist and/or fascist. The other reason is less obvious. Organized labor preferred to negotiate for health benefits. A single-payer system might have threatened those hard-won victories to bargain collectively with the capitalists.

During the years of the postwar era, as the economy reached nearly full employment, union membership was high and the ranks of the middle class swelled, most Americans got their health insurance through their employers. For this reason, perhaps more than any other, President Obama would never be able to make a convincing political case for anything like single-payer universal health care in 2010.

Even his modest proposal to make Medicare accessible to those who preferred government insurance, what was called the “the public option,” was a political dead end. Most Americans are risk-averse when it comes to something as important as health insurance. If they can’t see how something benefits them immediately, they won’t give up what they have — no matter how bad, broken and unjust it may be.

Medicare for all is probably the best policy — cheaper, higher quality, more efficient. And given the 30-year trend in which businesses are abandoning the social contract by not insuring workers, Medicare for all is likely the best long-term solution. Yet we may get there still, and if we do, it will be in unexpected ways. Here’s what I mean.

In 2010, the politics were not in Obama’s favor, even with record levels of unemployment. Not only were Americans still accustomed to employer-based health insurance, and therefore risk-averse to anything new, but those already inclined to believe universal health care was another name for “socialized medicine” were encouraged to continue thinking just that by a $100 million campaign, replete with television attack ads by an insurance lobby, had hopes to kill the bill.

Obama met resistance even from his own party. Conservative Democrats in the Senate feared reprisal if they supported anything that sounded like “socialized medicine.” To avoid a filibuster, Obama dropped the public option and proposed what he figured everyone could get behind: a plan to raise the quality of health care, bring costs down and keep it all in the familiar world of free enterprise.

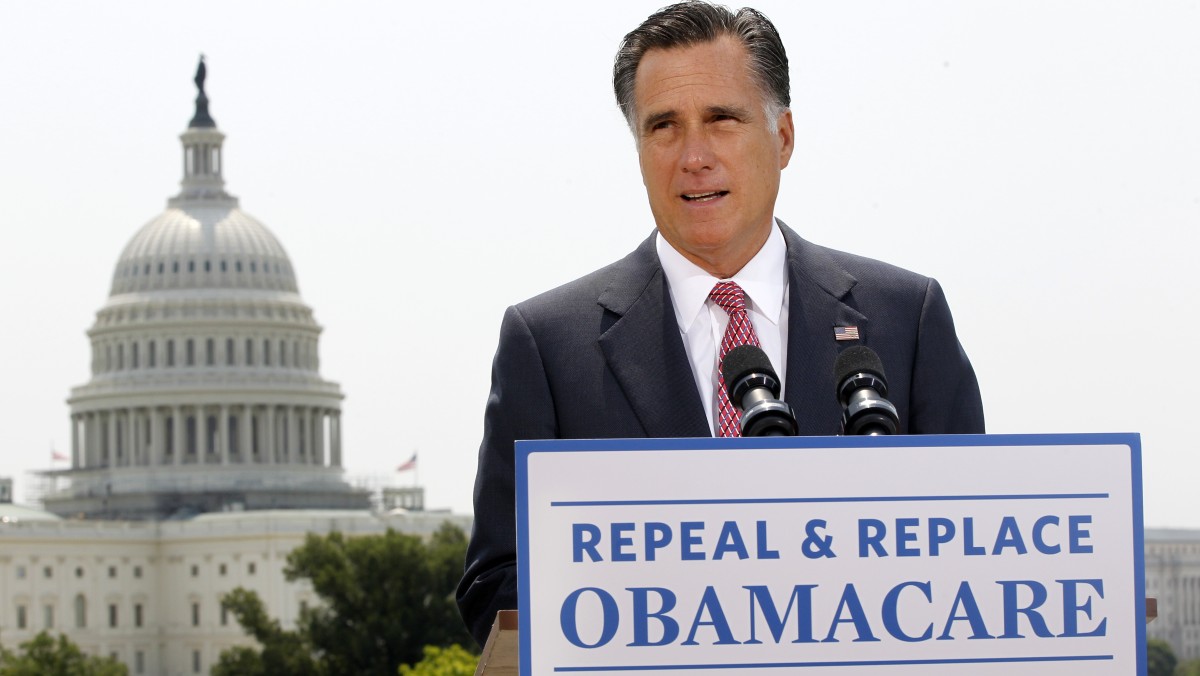

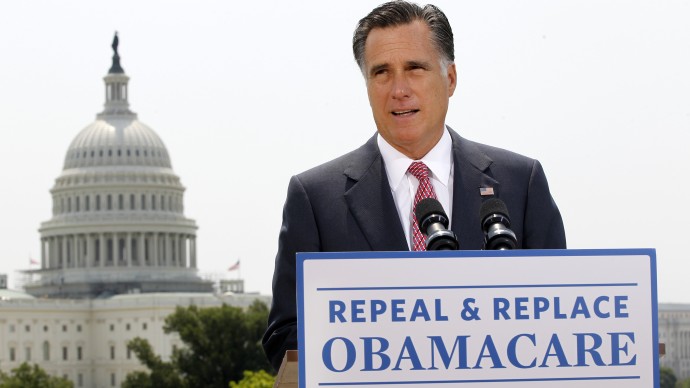

Which was, in fact, just what Mitt Romney recommended.

In 2009, as the debate over health care reform was heating up, the former Republican presidential candidate wrote an op-ed for USA Today and gave Obama some advice. If he hoped to enlist the support of skeptical Republicans and conservative Democrats, Romney said, Obama should forgot about the public option and do what he did when he was governor of Massachusetts: Force every state resident to buy health insurance. More than 98 percent of residents are now insured, emergency room visits are down and preventive care, critical to lowering long-term cost, is up. Called “Romneycare,” it obviated the need, the governor said, for “a European-style single-payer system.”

Our citizens purchase private, free-market medical insurance. There is no ‘public option.’ With more than 1,300 health insurance companies, a federal government insurance company isn’t necessary …. To find common ground with skeptical Republicans and conservative Democrats, the president will have to jettison left-wing ideology for practicality and dump the public option.

How did Romney get everyone to buy health insurance? Through something called “the individual mandate.” This was a legal strategy first innovated by the conservative Heritage Foundation in the late 1980s. It was used as a counterweight to President Bill Clinton’s proposal to require all employers to provide health insurance to workers. To conservatives at the time, an employer mandate like that seemed too onerous and insufficiently demanding of individuals.

Of course, Romney was only half right. After putting a variation of Romneycare on the table, the president did get the support of conservative Democrats and a couple of moderate Republicans in the Senate, but conservatives uniformly hated the law, and that was mostly because a Democratic president had co-opted a Republican strategy, then stood poised to be unstoppable force in 2012.

That’s why they challenged the mandate all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The government had no power to force anyone to buy anything, they argued. Doing so was federal power at its most despotic. The high court didn’t buy the argument and last week upheld the entire law, and now the Republican Party is calling for its immediate appeal.

We should consider the deep irony in this.

The GOP wants to repeal a law modeled after legislation enacted in Massachusetts by the party’s own presidential nominee, Mitt Romney. Central to that state’s law is the individual mandate, a concept first championed by Congressional Republicans who opposed the employer mandate proposed by a Democratic president. And that employer mandate was itself Clinton’s attempt to preserve the peculiar structure of the American health care system: employer-based insurance and not, as Romney later put it, “a European-style single-payer system.”

And deepest irony of them all is this: For all these attempts to circumvent the need for establishing a nationalized single-payer health care system, or Medicare for everybody, we may, with a reformed Obamacare, end up over the next many years with exactly that.

Romneycare has over six years achieved its initial goal. Less than 2 percent of the Massachusetts population is uninsured. According to three independent studies, 68 percent of residents receive coverage through an employer, emergency room visits are down by 4 percent and the number assessed a “tax,” or penalty, for not buying insurance has also dropped (44,000 in 2010, down from 67,000 in 2007). And critically, the more people know about the law, the more they like it. More than 60 percent of residents say they support the law despite the penalties, which is twice what Obamacare currently enjoys.

Such is the future for Obamacare, a future that includes the stubborn persistence of high costs. Neither Romneycare nor Obamacare dictates premiums that firms can charge, which are up by roughly 15 percent in Massachusetts. The state legislature is now shifting its focus from universal coverage to controlling the cost of that coverage, and it is studying various ways of doing that. The same probably goes for future Obamacare legislation. As premiums continue to rise, they will spark new reforms. The Affordable Care Act is just the beginning.

Obamacare does dictate the percentage of your premium that goes to actual health care coverage. This is called the medical-loss ratio, and insurance companies have for years put a lot of your money into things like advertising. Obamacare requires firms to spend 80 percent of premiums on care. According to Rick Ungar of Forbes, this will preclude insurers from making a profit. If they could, they wouldn’t have tried so hard to deny coverage precisely when it’s needed.

“So, can private health insurance companies manage to make a profit when they actually have to spend premium receipts taking care of their customers’ health needs as promised? Not a chance … They know what we should all know –- we are now on an inescapable path to a single-payer system for most Americans and thank goodness for it,” Ungar wrote.

With the government writing the rules, such as cost-effective fee schedules and a high medical-loss ratios, we may see something extraordinary happen to the American health care system over the coming years — for-profit insurance companies that used to reward executives with millions becoming more like public utilities.

As they should. Health care is too important to entrust to the profit motive. This is going to take a long time, but it will likely happen given how domestic programs of this size never go away once they have taken root (think Medicare). The slow pace of change ought to satisfy conservatives, and the final transformation ought to satisfy liberals.

Over time, health care insurance provided by regulated public insurers may become such a fixture in American life that we forget where they come from, but know they are vital. Indeed, perhaps some day we will hear someone say: Keep your government hands off my Obamacare.