“As I’ll explain more fully in a moment, this change in our guidance does not indicate any change in the committee’s policy intentions as set forth in its recent statements. … Let me explain the economic outlook that underlies these actions.”

That may not sound like a small revolution in the works, but Janet Yellen, on the job for less than a month, meant every bit of it. She actually explained what the Federal Reserve is looking at and how it sets the policies that drive the world.

Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan famously said, “Since becoming a central banker, I have learned to mumble with great incoherence. If I seem unduly clear to you, you must have misunderstood what I said.” It was the gold standard for being a Fed chairman, and the markets loved it.

Ben Bernanke was always much more open about the internal debate on Fed policy, even encouraging governors who disagreed with him to speak openly. His tenure was rocky, but his hand was generally firm on the tiller. Markets learned to love Bernanke, especially as he pumped money into the economy at an unprecedented rate.

Yellen, for her part, opened up even further in her first press conference on March 19. The “taper” of $85 billion per month in mortgage-backed bonds since August 2012, down to $75 billion in January and $65 billion in February, will continue — and be done in six months. After that, expect interest rates to rise.

But the most direct and open thing that came out of her remarkable press conference was Yellen’s direct revelation of what is on her “dashboard” to measure economic recovery.

U6 – Yellen mentioned the broadest measure of unemployment several times. U6 is the measure that includes part-time workers and those who gave up looking for work.

“Certainly look at broader measures of unemployment. …With 5 percent of the labor force working part‐time on an involuntary basis, that is an exceptionally high number relative to the measured unemployment rate. And it ‐‐ so to my mind, it is a form of slack that is ‐‐ adds to what we see in the normal unemployment rate and is unusually large.”

Long Term Unemployment

“The share of long term unemployment has been immensely high and can be very stubborn in bringing down. That is something I watch closely. Again, that remains exceptionally high. But, it has come down from something like 45 percent ‐‐ high 30′s ‐‐ but that’s certainly in my dashboard.”

Workforce Participation

“I do think most research suggests due to demographic factors, labor force participation will be coming down and there has been a downward trend now for a number of years. But, I think there is a cyclical component in the fact labor force participation is depressed. And so it may be that as the economy begins to strengthen, we could see labor force participation flatten out for a time as discouraged workers start moving back into the labor market, and so that’s something I’m watching closely, and the committee will have to watch.”

Quit Rates – This is the surprise.

“I take the quit rate in many ways as a sign of the health of the economy. When workers are scared they won’t be able to get other jobs, they show a reduced willingness to quit their jobs. Quit rates now are below normal pre‐recession levels.”

In other words, we will know the economy is healthy when people are leaving their jobs for better ones.

Wage Growth

“With productivity growth, we have, and two percent inflation, one would probably expect to see on an ongoing basis something between perhaps three and four percent wage inflation would be normal. Wage inflation has been running at two percent.”

These five gauges on the dashboard are a remarkably clear statement of how the Fed will set rates going forward, but taken together, they show how tightly focused the Fed is on jobs in the United States. This is both unusual and outside of the classic role of the Fed.

“Due to its narrow set of policy tools — Congress has better ones but is paralyzed by polarization and dysfunction — the Fed has no choice but to bolster equities (and Wall Street) as a way of pursuing its growth and employment objectives,” wrote Mohamed El-Erian, a leading bond trader.

There is considerable evidence that Fed policy has been driven by what political economist Robert Reich called “the Fed’s jobs program,” or the program of buying mortgage-backed bonds since September 2012. He was responding to Bernanke’s extraordinary statement at the time that “the conditions now prevailing in the job market represent an enormous waste of human and economic potential.”

By most considerations, the Fed has indeed kept interest rates well below what the market might otherwise demand.

The exact way the Fed picks a rate is a mystery. In 1993, Stanford economist John B. Taylor proposed what is now known as the “Taylor Rule” that balances out the various forces in the economy and predicts an optimal federal funds rate. It is presumed that this is the main guiding force the Fed uses to set rates.

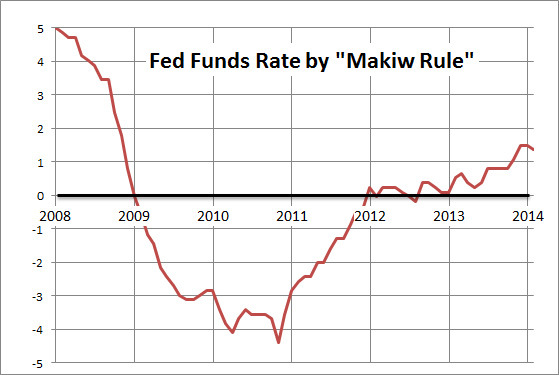

The problem with the Taylor Rule is that it is complex and contains a lot of math. In 2003, Harvard Economist Greg Mankiw proposed a simpler version that eliminated most of Taylor’s variables and produced a very simple formula:

Federal funds rate = 8.5 + 1.4 * (Core inflation – Unemployment)

“Core Inflation” is the rise in prices other than volatile food and gasoline, and Unemployment is the headline U3 unemployment rate. It seems to hold pretty well, and it does predict roughly where the Fed sets the federal funds rate. Graphing this from 2008 to today gives us this chart:

Note that in January 2009 the calculated rate suddenly drops off below zero. You can’t have an interest rate below zero, so the Fed set their rate to zero and started “Quantitative Easing” (QE), or easing up the supply of money with a fixed quantity of money rather than by setting rates.

The first QE was a modest one, a $300 billion purchase of Treasury Bills, or U.S. government debt, in January 2009. But that came after an $800 billion stimulus in November 2008 to shore up weak markets after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. That was QE1, for lack of a better name. This was followed by another $600 billion in November 2010 (QE2), and then in September 2012, the purchase of $85 billion per month in mortgage backed securities (QE3, now $1.5 trillion and counting), tapered starting in 2014. Altogether, it’s $3.2 trillion.

But the calculated target interest rate turned positive in 2012, and is about 1.5 percent today. This is the best measure of the Fed’s commitment to job growth. As Reich said, “Two cheers for Ben Bernanke and the Fed. They’re doing what they can. The failure is in the rest of the government.” Yellen, for her part, is clearly continuing that policy.

Yellen told us exactly what to expect. We can expect the Fed’s job program, QE3, to end by this summer. After that, interest rates should rise. What’s on her dashboard, however, is primarily the state of jobs in our economy, even though the classical rate determination formula tells us the Fed is already running a very hot stimulus.

Between this new openness and deep commitment to job creation, the Federal Reserve is more public and activist than it ever has been before. It is an interesting start to Yellen’s tenure at the head of it.