Palestinian Greek Orthodox Archbishop Atallah Hanna, center left, walks beside Sheikh Hatem al-Bakri, center right, on a street to protest against a cartoon of Islam’s Prophet Muhammad that was published by the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo last week as protesters march in the West Bank city of Hebron, Thursday, Jan. 22, 2015. Photo: Nasser Shiyoukhi/AP

Palestinian Greek Orthodox Archbishop Atallah Hanna, center left, walks beside Sheikh Hatem al-Bakri, center right, on a street to protest against a cartoon of Islam’s Prophet Muhammad that was published by the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo last week as protesters march in the West Bank city of Hebron, Thursday, Jan. 22, 2015. Photo: Nasser Shiyoukhi/AP

MINNEAPOLIS — The January terrorist attack against the Charlie Hebdo magazine over cartoons ridiculing the Prophet Muhammad ignited a heated global debate over whether freedom of speech can be taken too far. It also raised questions of how negative depictions of the prophetic leader of France’s Muslim working class, Muhammad, can lead to violence as well as negative sentiment toward the country’s already ostracized Muslim citizens.

In a show of support for both free speech and the victims of the terror attack at the offices of the French satirical magazine, world leaders gathered to march on the streets of France. Although iconic, it was also ironic to see leaders of nations with notorious records of human rights abuses and limited press freedoms — including Israel, Jordan, Turkey and Egypt — attend the march.

In France, too, freedom of expression took a hit with laws making it illegal to question the Holocaust or even protest in support of occupied Palestine, among other things. Even at the magazine of Charlie Hebdo, which turned a practice of mocking Muslims into a money-making machine, at least one cartoonist had been fired in the past for depicting Jews in a negative light.

So, are events like the solidarity march about defending free speech in its broadest sense? Or is it about defending attacks on an already disenfranchised community — attacks which perpetuate offensive stereotypes, promote dangerous hostilities, and ultimately contribute to maintaining the “us vs. them” dichotomy to justify modern-day colonialism in Muslim nations?

While the individual attackers should be held accountable for their heinous actions, how much responsibility should the media shoulder in these events? Every word or image painted by the media is powerful and can change the course of history. They can impact the world, for better or for worse, and cause ripple effects within society that eventually lead to movements, either positive or negative.

In Rome, in fact, satirical images brought attention to inequality and ultimately contributed to the rise of a revolution there. Exploring other parts of history, we can see two iconic images that left indelible marks on the world.

The Wandering Jew

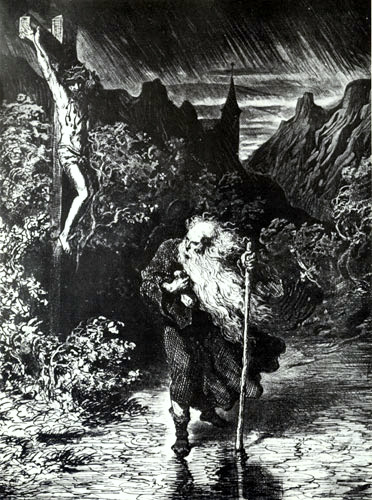

In 1856, Gustav Doré, a French illustrator, created a series of illustrations of “The Legend of the Wandering Jew” to accompany a poem about the Biblically-derived legend that had been sweeping Europe since the 13th century. Doré’s image depicts the shoemaker from Jerusalem, who, as legend has it, taunted Jesus during the Crucifixion. In return, Jesus told the shoemaker to “go on forever till I return,” a reference to the Second Coming of Christ.

Gustav Doré’s 1856 “The Wandering Jew”

Gustav Doré’s 1856 “The Wandering Jew”

Historians have pointed to Doré’s Wandering Jew as the image which shaped how Europeans viewed Jews — as “rats” wandering the earth.

Indeed, decades of reproducing Doré’s image contributed to extreme anti-Semitism, and it is cited as eventually justifying the Holocaust by the Nazi-led Christian Aryan movement — a movement which insinuated that Jews were dirty like rats because they were “wandering” the earth, carrying disease. This eventually led to an expulsion of Jews from Europe to create a Jewish-only state on historic Palestine, which then led to the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian population.

It’s interesting to note that French cartoonists, in particular, have been using images to perpetuate dangerous stereotypes and push boundaries for centuries. Charlie Hebdo is merely the latest outlet to make such an impact on the way Europeans view the adherents of a particular religious tradition.

Passion of the Christ and the Anti-Christ

Passion of the Christ and the Anti-Christ

Another iconic political cartoon contains two cells: One shows a crown of thorns being prepared for Jesus, while the other depicts a crown of gold and jewels being prepared for the pope. Commissioned by Martin Luther, this cartoon sparked a revolution against the money- and power-hungry Vatican, which had a strong grip on power at the time, and eventually led to a schism within the Catholic Church and the founding of the Protestant Church in the 16th century. When the outraged Vatican approached Luther about the illustrations accompanying his writing, he cited “satire” to justify the inspiring images.

Indeed, Luther used satire alongside this illustration to generate outrage among the starving masses over the vast wealth held by the Catholic Church. Images like these were particularly important for spreading a message at a time when literacy wasn’t prevalent among the majority of the people — one didn’t have to be able to read to get Luther’s message.

Taken together, these images represent the power that some ink on paper can have over not just a contemporary audience, but future audiences, as well. Images and satire can frame an argument, push an agenda, and give people something to rally behind — even without words. Whether it’s inciting religious hatred or rallying the masses against a major money-hungry power, images can turn the tides of history.

Considering this power, where can we draw the line between granting the person holding the pen unlimited freedom of speech and when should a sense of respect for another person’s dignity enter the equation? Of course, everyone should be able to voice his opinion without concern for censorship, even via a cartoon, but at what point does it cross a dangerous line? How can society differ if it’s simply not going to contribute to the greater good, but rather to hate, intolerance and misunderstanding?

Or, by poking at sensitive issues through satire and a no-holds-barred attitude, are magazines like Charlie Hebdo providing us a mirror to reflect upon our own biases and attitudes and possibly the attitudes of elitists who want to dehumanize the victims of our endless war on terror in Muslim nations?

No matter the answers to these questions, one thing is certain: Cartoons are powerful. They influence thoughts and attitudes in a way that demands that we hold their creators accountable for the events their work can give rise to.

Indeed, rather than using cartoons to push agendas full of hate, fear and segregation, artists should be harnessing the massive power of the image toward positive ends, like raising awareness around inequalities and social issues or calling out abuses of power and hypocrisy.