TEHRAN, IRAN — On April 25, the Saudi-funded and U.K.-backed “Iran International” released a leaked audio recording of Iran’s foreign minister, Javad Zarif, in conversation with Iranian economist Saeed Laylaz for what appeared to be an oral history project. Immediately, the three-hour-plus conversation generated a great deal of controversy in Iran and plenty of commentary abroad. In the course of the conversation, Zarif spoke about his diplomatic posts, before and during the Rouhani administration, and his future political ambitions (or lack thereof). He ruminated on his relationship with President Hassan Rouhani, the late General Qasim Soleimani, and the leader of the Islamic Republic, Sayyid Ali Khamenei. He also highlighted his political philosophy on Iranian sovereignty and on international relations, as he discussed relations with the U.S., Russia, and Saudi Arabia, among other nations.

In the Anglo-American sphere, regime change evangelists, mainstream news, native informant media in Persian, and radlib analysts found their characteristic convergence: they distorted through an imperialist discourse redolent with confirmation bias what they had heard (or, in some cases, misheard). Two narratives emerged. The first advanced the tired trope of oriental despotism. Emerging out of colonial and liberal discourses and carrying into the present day, this trope imagines a dichotomous world between Western political agency and freedom on the one hand and an oriental or Muslim tyrant on the other, who rules through total control of his bureaucratics and subjects. The second narrative centered not so much on Russia’s despotism (although both the Soviet Union and Russia have received their fair share of such representations), but on the post-2016 obsession of the Democratic Party with Russia as the spoiler of “our democracy” — subject to a slight twist in this case, as the U.S. media represented Russia as the sole spoiler of the “Iran Nuclear Deal.”

The tired trope of oriental despotism

The usual suspects, including The New York Times, ginned up these narratives. As regards to the first narrative of oriental despotism, with no traceable support from the tape’s transcript, the Times reported: “Decisions, [Zarif] said, are dictated by the supreme leader or, frequently, the Revolutionary Guards Corps.” The Times went on to quote an Atlantic Council pundit stating that “Iran’s foreign policy is dictated by theater policies of the military and Zarif is a nobody.”

Despite the sensationalist focus on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Zarif mentioned them only once during the entire interview. This was in reference to Iran’s National Security Council wherein the IRGC receives representation through a general with observation (nazir) status but without a right to vote on issues (18; this and subsequent page numbers refer to the transcript of the recording). The IRGC organization received a single reference, but its late general, Qasim Soleimani, was mentioned several times, along with the leader (rahbar), Khamenei.

Let’s start with Khamenei and test the “dictation” claim of the Times. Zarif mentioned Khamenei in 11 different segments of the interview, 10 times by the title of his office and once by an honorific. In none of them did Zarif indicate or imply that the leader (or the leader’s office) “dictated” the entirety of foreign policy. Rather, Zarif spoke of his relationship with the leader, in which the latter’s authority and revolutionary credentials stood out. Khamenei, Zarif claimed, despite his revolutionary function, “is one of the strongest diplomats of the nation,” evidenced in his interactions with foreign representatives in Tehran (18).

As the commander-in-chief, Khamenei does direct the country’s foreign policy. Khamenei’s general direction did not mean, however, that Zarif had no agency in diplomacy. One segment is particularly supportive of Zarif’s agency: Khamenei had reproached Zarif in response to a February 2021 interview Zarif had given to CNN’s Christiane Amanpour on the return to the nuclear deal. According to Zarif, his comments were misinterpreted by BBC Persian to say that the U.S. and Iran must return to compliance with the nuclear deal simultaneously, which went against the official Iranian policy that the U.S., as the party that had abandoned the deal, must be first to return. Khamenei then wrote Zarif a “compassionate” but “firm” letter to express his concern over this apparent divergence from state policy. Zarif responded in a seven-page letter, explaining that his comments had been misinterpreted (17). Now former U.S. President Donald Trump might have fired his minister in such circumstances, but Khamenei simply responded that Zarif’s explanations were “beneficial” (17).

On other occasions, Zarif engaged in conduct that did not meet Khamenei’s expectations. For example, he was cleared to meet with former U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry but the meeting became much more formal and extended than the one Khamenei had expected (22-23). It should follow that Khamenei exercises authority and direction over foreign policy, and this reinforces, and at times conflicts with, Zarif’s diplomatic agency and judgment. The idea of dictation therefore as presented to us by the mainstream media simply reads oriental despotism into the content of the tape and is not supported by anything Zarif actually said.

Zarif and Soleimani

Next, we come to Zarif’s relationship with Soleimani. Soleimani was mentioned during the interview 52 times, but without any indication that the general’s role (or the organization of IRGC he represented) reduced Zarif to a “nobody.” Rather, Zarif spoke about his disagreements with Soleimani, despite his deep affection for the general, and the lack of reciprocity between him and the general, telling his interlocutor that “the general and I were not necessarily agreeable on all issues but we felt that we had to coordinate and we did this — and I can say this confidently, that I compromised on diplomatic objectives for military ones, but the reverse was not true” (25).

For example, Zarif requested that Soleimani not use Iran Air for flights between Tehran and Syria, which the general refused. Zarif, on the other hand, complied with Soleimani’s requests to put pressure on the Russian foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, to “liberate” Al-Fu’ah and Kafriya in the Idlib province of Syria in exchange for the release of civilian prisoners in Aleppo (26). In the tape, Zarif faulted for this lack of reciprocity the policy of “the state as a whole” (kull-i nizam), where the military objective had primacy over diplomacy (27). Zarif differed from this official policy, he said and believed that primacy lay with preserving revolutionary values, all the while pushing for “the [diplomatic] management of difference” with the imperialist United States, in lieu of indefinite enmity and the securitization of national discourse and policy (13).

Contrary to the Atlantic Council’s confusion, then, Soleimani did not reduce Zarif to a nobody. Rather, with respect to military and diplomatic objectives, Zarif felt, contrary to his own preferences, that “the state as a whole” converged on the primacy of military objectives, which then led to a lack of reciprocity between him and Soleimani.

One lens for the West, another for the rest

Now, the double standards when it comes to the West and the rest are quite telling. If a U.S. official said they were unable to implement a policy because of resistance from the Pentagon and the military brass, it would not be taken as proof that this official was a nobody; but when an Iranian diplomat says the same, it is cynically portrayed as a smoking gun that can only be interpreted through the tired trope of oriental despotism. Indeed, I’d like to make the bold suggestion that the differences Zarif was grieved about indicate the relatively higher degree of pluralism in the Iranian political system when compared to the United States.

In the U.S., at the federal and mainstream levels, it is difficult to find variance within foreign policy discourse and objectives. Foreign policy is uniformly belligerent — there is no shame exhibited that the two bipartisan standing ovations at the 2020 State of the Union were in response to Trump’s promotion of Juan Guaido, and his even more repulsive celebration of Soleimani’s assassination. Compare this with Iran, where at the national and mainstream level, you have great disagreement.

On foreign policy, some (including, the so-called “hardliners”) want zero engagement with the West, as they think, based on colonial history, that their agreements are mere bad-faith theater; whereas others, such as officials in the Rouhani administration, view national progress as inevitably linked to the “management of difference” with the West and incorporation into the global markets. Foreign policy discourse is more plural and varied among the Iranian political elites (and one should add, the general public) than it is in mainstream U.S. politics. Much of the public consumes this politics through the mainstream media without self-reflection, and it is only the American anti-war movement that has endeavored to hold imperialism accountable.

A simplistic narrative for a complex set of relationships

This brings us to the mainstream media’s second narrative: the vilification of Russia as the agent against diplomacy. As with the U.K. and the U.S., Iranian politics approaches Russia with anxiety. Iran still holds collective memories of the Tsars, to whom Iran suffered territorial losses in the 19th century; followed by the Tsar-backed bombardment of the nascent Iranian parliament in 1908; and then the carving up of Iran into English and Russian “spheres of influence” during World War I. Speaking in this context, Zarif viewed Russia with caution, telling us that a crisis between the West and Iran was not in Russia’s interest but neither was normalization, and this was why Moscow opposed the nuclear deal (33).

When the JCPOA (the formal acronym for the nuclear deal) was signed, the Russian foreign minister, Lavrov, was not in the collective picture, and he had put in his utmost effort to stop the deal, words that Zarif said to his interlocutor “you will never be able to publish” (31). Examples of these efforts included a later-discarded text of the agreement presented by the U.S. team to Iran, drafted by Russia but also France, specifying that Iran must seek a vote from the Security Council every six months for the renewal of JCPOA (34). Zarif added that Russia also attempted to obstruct the deal by raising tensions. It attempted to generate indefinite reliance on Russian industries and contractors for Bushehr’s nuclear power plant, whereas Iran wanted temporary Russian assistance after which it would become self-reliant.

Russia also refused, Zarif added, to provide a license to Iran for the use of its own fuel in the plant. It appears from the tape that the two countries reached an agreement, however, according to which Iran would become self-reliant after a ten-year period (32).

According to Zarif, then, Russia attempted to obstruct the nuclear deal before its conclusion on July 14, 2015. However, the mainstream media omitted crucial parts of the transcript. Zarif also added that “Russia is our neighbor and it is important to maintain our relations” (33). In fact, when it came to the diplomatic realm, Zarif appeared more aggrieved with the Americans. What follows is not an exhaustive list of his grievances during the interview, but the most contemporary events that he mentioned.

Zarif’s nuanced views of Russian and American behaviors

Early on in the interview, Zarif expressed dismay regarding the Biden administration, saying that it is not much different from Trump in its treatment of the Iranian people: “What I see right now [early 2021] is that the people are still having problems in their purchase of medicine, food, and imports, and more than [$]10 billion of our money is frozen” (2). Moreover, Zarif expressed contempt at the controversial December 2015 H.R. 158 legislation, which he claimed was achieved through the advocacy of the Zionist lobby. H.R. 158 barred dual nationals of Iraq, Syria, Iran and Sudan, as well as foreigners who have traveled to these countries since March 2011, from eligibility in the U.S.’s visa waiver program. Zarif added that Barack Obama’s refusal to veto it, after his request to Kerry, went against the spirit of the nuclear deal concluded some five months earlier.

There were even more diplomatic grievances against the United States. Zarif alleged that the U.S. misrepresented the Yemen war to the public, shifting the blame from Saudi Arabia (and, one might add, itself) to Iran. According to Zarif, in the spring of 2015, shortly before the nuclear deal was concluded, a multilateral ceasefire was about to be concluded in Yemen. Even though Zarif never spoke to Kerry on Syria, he discussed Yemen with him, spending two precious days on the issue in Lausanne, Switzerland during the nuclear negotiations.

Kerry telephoned Zarif as the latter was traveling to an Islamic nation conference taking place in Indonesia. Kerry told Zarif that he and then-Saudi Foreign Minister Adel bin Ahmed Al-Jubeir had reached an agreement towards a ceasefire in Yemen. Zarif was delighted, as he knew the Houthis (Ansarullah) were already agreeable to a ceasefire. Zarif then contacted Hossein Amirabdollahian, the Iranian deputy foreign minister on Arab and African affairs at the time, who then communicated with Soleimani — who, Zarif said, was sincerely against the Yemen war because of its human cost. Soleimani then communicated with the Houthis to finalize the ceasefire.

At this point, Zarif met Saudi representatives in Indonesia’s Islamic conference and inquired about the outcome of the ceasefire, and they told him it was off. Zarif called Kerry to inquire and he was told that “Ahmad bin Salman [sic] had backtracked,” thinking that the Saudis would win the war in three weeks. The timeline of the event points to Saudi Arabia’s uninterest in following up on their own ceasefire plans; yet, Zarif added, Obama gave a speech the next day, blaming Iran for the war’s continuation. Zarif ended this segment by adding that the U.S. repeated such behavior that undermined diplomacy many times (54-55).

Accordingly, Zarif presented us with a mixed picture of those who refused diplomacy. Russia was only one part of the story and on one particular issue (the nuclear deal). A careful assessment of the interview shows that the U.S. received more criticism. Moreover, Zarif’s opponents in Iran who gave primacy to military objectives over diplomatic ones received their fair share of criticisms; and, of course, the Saudis, who, Zarif told us, pursued continued assault on Yemen against the terms of a multilateral ceasefire (57). Indeed, the mainstream media’s singular obsession with Russia as the anti-diplomatic force shows more about internal American politics than it does about the Zarif interview or Iran-Russia relations. With Zarif’s tape, there is now new material to embellish and color anew the Russiagate hysteria.

Real consequences and propaganda campaigns

The source of the leak and the motivations for its release are still not clear, despite conspiratorial claims by some that the leak was a coordinated “inside job” (min 11:34-12:12) to create an illusion of difference within Iran’s political system in anticipation of the 2021 presidential elections. These conspiracies lack evidence thus far, but the U.S. and their proxies in the Iranian media give them visibility, as it appears that it is only concerning Western politics that one must produce evidence-based claims! If more information emerges, we can make better assessments on the source and motivations for the leak.

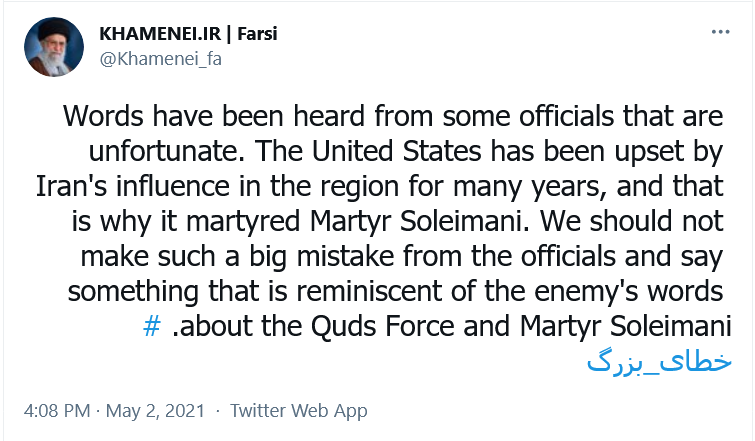

On May 2, Khamenei’s Twitter expressed “regret” over Zarif’s comments without naming him. For now, it remains to be seen whether the tape will impact Zarif’s political future in Iran. Khamenei, the IRGC, party and parliamentary politics, and the public will all play a role in how this future plays out.

Moreover, it remains to be seen whether the tape will have any impact on the ongoing attempts to revive the nuclear deal that the Trump administration abandoned in May of 2018, after which the Western media engaged in a ludicrous gaslighting campaign against Iran for lack of compliance. One clear consequence is already here, however: the reading of the tape, not to evaluate American foreign policy, but to extend the propaganda campaigns against Iran and Russia.

Contrary to what the U.S. media tells us, in Iran intellectual opinion is generally critical of state power and of the information the public receives; but, in the United States, the state, the media, the pundits and intellectual opinion, with some exceptions, all converge to see the Zarif tape as they want to see it. They have plenty of time to tell tales about their invented villains, to project their own political flaws onto Iran and Russia; but then there is no space for self-reflection and reform.

Feature photo | Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif prepares to speak with journalists following a conference in Tehran, Feb. 23, 2021. Vahid Salemi | AP

Navid Zarrinnal is a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University specializing in Iranian history. He is currently based in Tehran and can be reached at [email protected]