THE HAGUE, Netherlands — As Palestinians in the Gaza Strip continue to mourn the losses of last summer’s Israeli military offensive, which killed 2,251 Palestinians in the besieged enclave, including 551 children, over 51 days, Israel increasingly risks new legal repercussions for its actions.

“It’s obvious that war crimes were committed during the assault on Gaza, horrible crimes that are shameful for humanity,” Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor chairman Ramy Abdu told MintPress News from the Geneva-based group’s Gaza office.

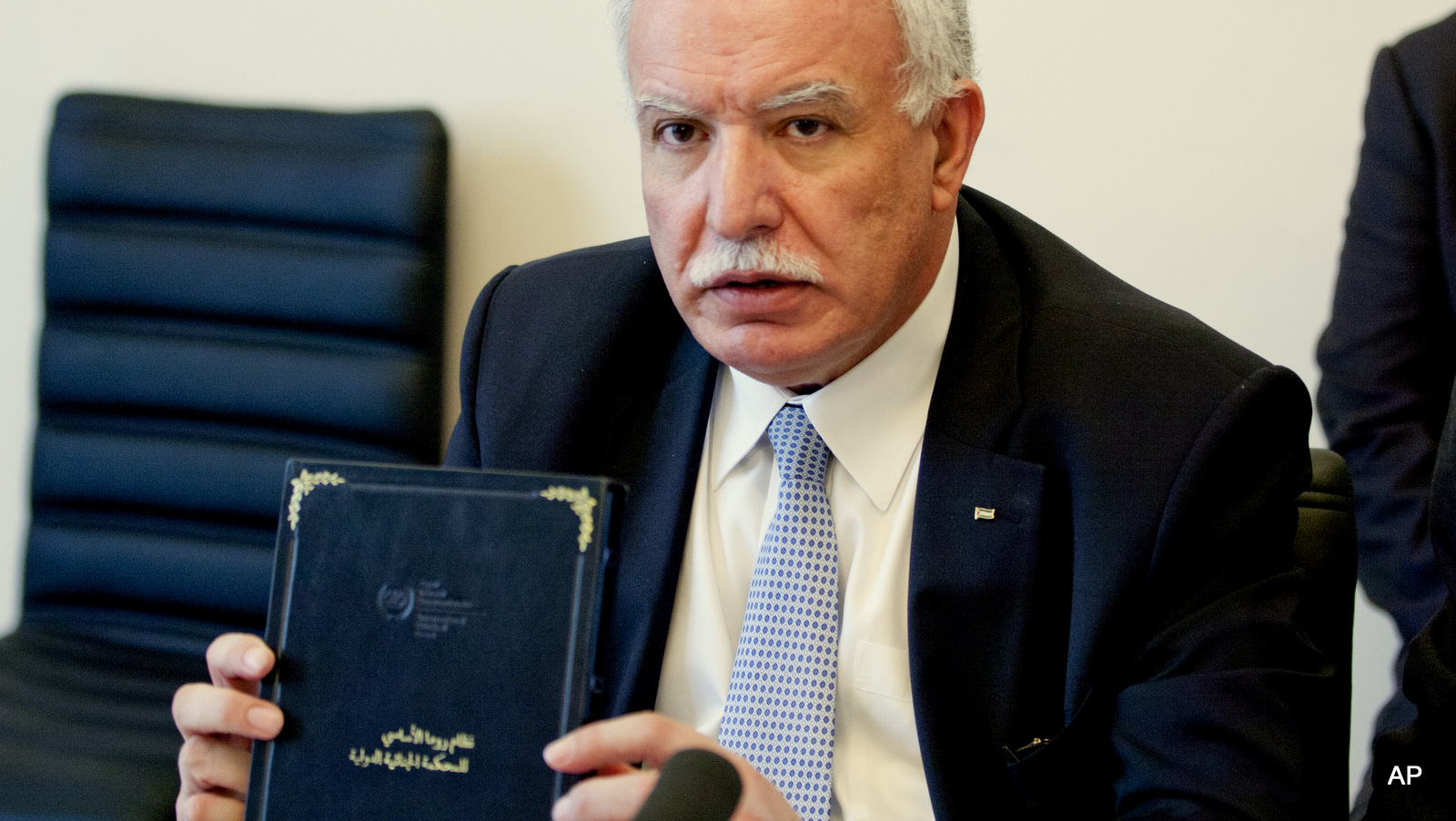

After the State of Palestine’s application to join the Hague-based International Criminal Court on Jan. 1, its membership on April 1, and the submission of its first complaints to the ICC on June 24, Israel faces a range of possible charges.

According to Shawan Jabarin, director of the Palestinian human rights group Al-Haq, who spoke to Mondoweiss after the documents were filed, their contents included not only expected complaints stemming from Israel’s bombardment of Gaza and construction of settlements in the West Bank, but also others about its treatment of Palestinian prisoners, as well as allegations of the crime of apartheid as defined under the ICC’s founding Rome Statute.

The dossier included 23 counts, Jabarin said, including seven war crimes.

The official Palestinian effort brings together Jabarin and 31 other members in a national committee, appointed by Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas on Feb. 7, which stretches across the often fractious spectrum of Palestinian internal politics.

Multiple threats

But its filings are only one of multiple threats now facing Israel at The Hague.

On Jan. 16, ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda launched her own preliminary investigation into events in the West Bank and Gaza Strip since June 13, 2014, the period of jurisdiction granted the court by Palestinians when they joined it.

Many observers agree that the investigation has proceeded more rapidly than most, although an ICC delegation scheduled to visit Palestine at the end of July recently postponed its trip until the fall, citing technical and procedural reasons.

Within Gaza, the ICC’s investigation is expected to broadly follow the pattern of a U.N. Independent Commission of Inquiry’s report on the 2014 offensive, which cited potential “war crimes” by both Israeli forces and Palestinian resistance groups.

Additionally, Palestinian human rights groups are compiling complaints from individuals and organizations affected by Israeli operations in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

They range from Gaza Strip residents whose family members were killed by Israeli strikes last summer to West Bank landowners who have lost their holdings to settlement expansion.

Sources at groups in both Palestinian enclaves tell MintPress that while the number of cases has strained their capacities, the total could ultimately reach into the tens of thousands.

Freedom Flotilla

Another case pending against Israel stems from its May 31, 2010 attack on the first Freedom Flotilla, which attempted to defy its naval blockade of the Gaza Strip.

The assault by naval commandos on the flotilla’s lead vessel, the massive Mavi Marmara, killed eight Turkish activists and one Turkish-American.

Another Turkish participant died on May 23, 2014, after spending nearly four years in a coma.

A U.N. fact-finding mission determined that, “On the basis of the forensic and firearm evidence, at least six of the killings can be characterized as extra-legal, arbitrary and summary executions.”

On May 14, 2013, the Union of the Comoros, which had flagged the Mavi Marmara, referred the case to the ICC, claiming:

“The conduct of the IDF constituted Crimes Against Humanity, in that it included acts of murder, torture and ‘other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health’, which was committed ‘as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack.’”

An apparent rift

Last November, Bensouda dismissed the charges, saying: “[T]he potential case(s) likely arising from an investigation into this incident would not be of ‘sufficient gravity’ to justify further action by the ICC.”

But on July 16, the three judges of the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber I granted an appeal of Bensouda’s decision filed by the Comoros, finding in a 2-1 decision that she had “committed material errors” and requesting that she reconsider.

In their stinging review, the judges wrote:

“The Chamber cannot overlook the discrepancy between, on the one hand, the Prosecutor’s conclusion that the identified crimes were so evidently not grave enough to justify action by the Court, of which the raison d’être is to investigate and prosecute international crimes of concern to the international community, and, on the other hand, the attention and concern that these events attracted from the parties involved, also leading to several fact-finding efforts on behalf of States and the United Nations in order to shed light on the events.”

Days later, Bensouda lodged her own appeal against the judges’ decision, asking on July 27 that the ICC Appeals Chamber overrule it.

A crisis of legitimacy

The apparent rift between the ICC and its top prosecutor may hinge not only on technical questions of legality and jurisdiction, but also on concerns about the court’s waning legitimacy.

Over its 13 years, the court has overseen a total of 22 cases among nine situations, involving the prosecution of 30 individuals, each an African leader.

This narrow focus has not escaped notice on the continent, which has heard repeated calls for its states to withdraw en masse from the ICC.

The conflict came to a head at an African Union summit hosted by South Africa in mid-June, at which activists sought the arrest of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir on an ICC warrant.

Although a local court ordered al-Bashir to remain in the country, the South African government allowed him to return to Sudan on June 15, citing an agreement shielding AU summit attendees from arrest.

Little difference

The grant of immunity was little different from those repeatedly used by Israeli leaders, like Tzipi Livni, to avoid any possibility of arrest in friendly countries, such as the United Kingdom, that claim “universal jurisdiction” over crimes against humanity.

Nor was the deal, permitted by the Rome Statute, notably different from the “Article 98 waivers” the United States has signed with 95 other countries barring them from extraditing its nationals or employees for prosecution by the ICC.

But South Africa’s refusal to ignore its obligations as the summit’s host brought criticisms the ICC and its supporters had never leveled at non-African powers for similar arrangements.

With the AU currently discouraging its 54 member states from cooperation with the ICC, many see the Palestinian and Comorian cases as crucial tests of the court’s willingness to address violations of international law by a non-African state with Western support.

Political pressure

An official at the Palestine Liberation Organization’s delegation to the U.S. told MintPress the cases were not legally connected.

“The court took the decision on its own,” he said of the Pre-Trial Chamber’s challenge to Bensouda’s dismissal of the Comorian case. “We do not think that the issues are related.”

But for the ICC’s future standing, its treatment of the two could have a great deal in common.

From Gaza, Ramy Abdu, of the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor, said only political pressure on the ICC could prevent it from determining Israel’s guilt.

“We have no fears and there is no doubt that the outcomes of the investigation will show that Israel has committed war crimes,” Abdu said.

“If things go legally and away from any political pressure, or to say it more properly, if the parties withstand the political pressure, then we can say that those who are accountable for the war crimes will be under arrest very soon.”