The photo-sharing social media site Instagram has deactivated an anonymous, but popular account after it was discovered last week that the account was identifying witnesses who testified in cases involving violent crimes.

According to a report in the Philadelphia Inquirer, the account had nearly 7,900 followers and had identified more than 30 witnesses in the Philadelphia area since February, by posting photos, police statements and testimony.

The account was reportedly updated almost daily, and each post received dozens of comments and “likes” from subscribers, who largely advocated against the public helping the police.

Police in Philadelphia discovered the account, identified as rats215, when an officer from Philadelphia’s 12th district office ran across some photos of a witness and court records from a 2012 attempted shooting case, while monitoring Twitter. After finding that information on Twitter, the officer reportedly found the Instagram account.

What alerted the officer’s attention to this particular posting was that the case was handled by a secret-indicting grand jury — a practice approved by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 2012 in order to protect witnesses and increase conviction rates in violent crimes. Along with the creation of indicted grand juries came more extensive rules when it comes to disclosing statements from witnesses and victims.

For example, defense lawyers are allowed to go over the statements with their clients, but they cannot give their client a copy of any statements. Similarly, prosecutors only have to turn over statements two months.

In the case of the 2012 attempted shooting, in which a 19-year-old victim said he was shot at because he had testified in a homicide case, the grand jury case is not scheduled to begin until March, so those statements should not have been made public.

When the account was suspended, there were more than 150 published photos from the account. Authorities say that many of the statements that were posted were not public records, so officials are investigating the account to determine not only who was posting the information, but whether the account was part of a larger plan to intimidate witnesses.

Tasha Jamerson, a spokeswoman for the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office, said she wasn’t able to comment on the ongoing investigation, but said that the DA works with the Philadelphia Police to “investigate vigorously and thoroughly any attempt to intimidate any witness, to identify perpetrators and where appropriate, arrest and prosecute.”

She added that, “Unfortunately, witness intimidation continues to be a very serious, ongoing problem in the city of Philadelphia. We know that witness intimidation happens every single day at the [Criminal Justice Center].”

Authorities have reportedly identified a 17-year-old who they believe is responsible for the posts, and as of Nov.10 were still working on obtaining a search warrant to investigate the teenager further.

Leaked testimony

What concerns law enforcement is that one of the posts included photos and evidence from a shooting victim whose case was handled in a secret grand jury. Another post included a photo of a witness testifying in court.

One subscriber commented on one of the posts, saying “Post some new rats. I needa put a hit out on them,” while another commenter said, “This page is […] perfect.”

One of the posts praised Kaboni Savage, a North Philadelphia-based drug kingpin, who was sentenced to death in June for killing 12 people, including a firebomb that killed four children and two women. The Philadelphia Inquirer reports that the bombing was an act of retaliation against witness’ cooperation with the FBI.

In that post, rats215 posted a warning to witnesses that “we will get at you in time.”

Rats215 also routinely made posts asking followers to send paperwork on suspected “rats.”

The case is part of a growing number of online intimidation acts against witnesses in recent years, and will likely be used as further evidence by Justice Department officials as reason why federal courts should make it harder for the public to access court documents online.

But restricting the public’s access to court documents may not have made a difference in this case, since it’s not clear how rats215 was able to obtain some of the testimony.

Although statements are often times found in court records after a case is closed, the names of witnesses and victims are redacted for their protection. But the statements posted on the Instagram account contained the witnesses names and often their photographs.

Instagram officials shut down the rats215 account last Thursday after the company was approached by the Inquirer, and released a statement saying that the site “has a clear set of community guidelines which make it clear what is and isn’t allowed. This includes prohibiting content that bullies or harasses. We encourage people who come across content that they believe violates our terms to report it to us using the built-in reporting tools next to every photo or video on Instagram.”

Protecting witnesses

According to veteran law enforcement officials and prosecutors, often victims’ statements are posted in barbershops, on neighborhood light poles, and even mailed to witnesses’ homes. Now, thanks to the Internet, those statements are ending up on social media sites such as Facebook where even more people can see and share them.

“People feel they can hide behind a name,” Lt. John Walker of Southwest Detectives said. “It’s a challenge we’re facing and a challenge we’re attempting to work through.”

He added that investigators are working to determine the identify of rats215, saying, “These actions shoot an arrow through the heart of the criminal justice system, placing victims and witnesses at risk. [Accounts like rats215] should be voluntarily removed by the host of such sites.”

But the issue of witness intimidation, especially in Philadelphia, is a larger issue than social media sites can conquer by shutting down accounts.

In July 2012 the Philadelphia Inquirer editorial team published an editorial saying that hundreds of likely witnesses throughout the city have kept quiet, refusing to help police find the person responsible for firing a gun at a toddler during a neighborhood block party, out of fear they will be retaliated against.

“Their silence is a symptom of the callousness affecting too many neighborhoods where residents have become so accustomed to lawlessness that they chalk up the occasional shooting of a child as just part of living in the city,” the editorial says.

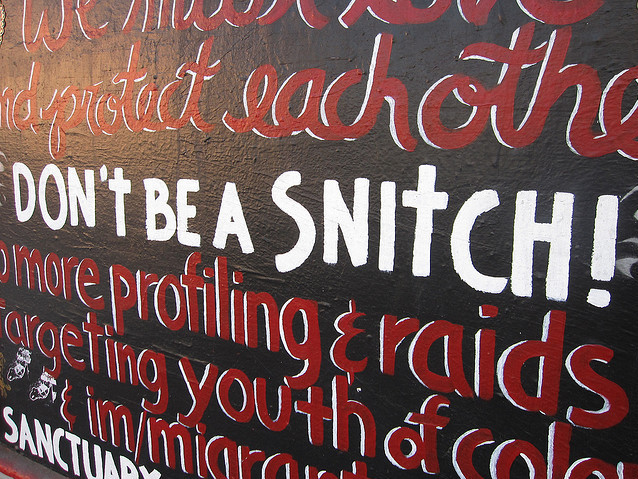

“But it’s really no surprise that in neighborhoods where the “no snitching” culture has become entrenched, criminals wield more power than law enforcement.

“People who have seen what happens to neighbors who cooperate with the police have a right to feel unsafe in their communities. They have little faith in witness protection programs that spring leaks. There’s also an almost hereditary mistrust of police in poorer, minority neighborhoods where memories of long-ago police abuses remain vivid.

“That means the police have a lot more work to do than solving crimes. They can’t be blamed for people not seeing that the only way they are going to make their neighborhoods safer is by getting rid of the bad seeds. But it is to the police’s advantage to do what they can to help people see that. And the city needs to give police the tools needed for that task.”