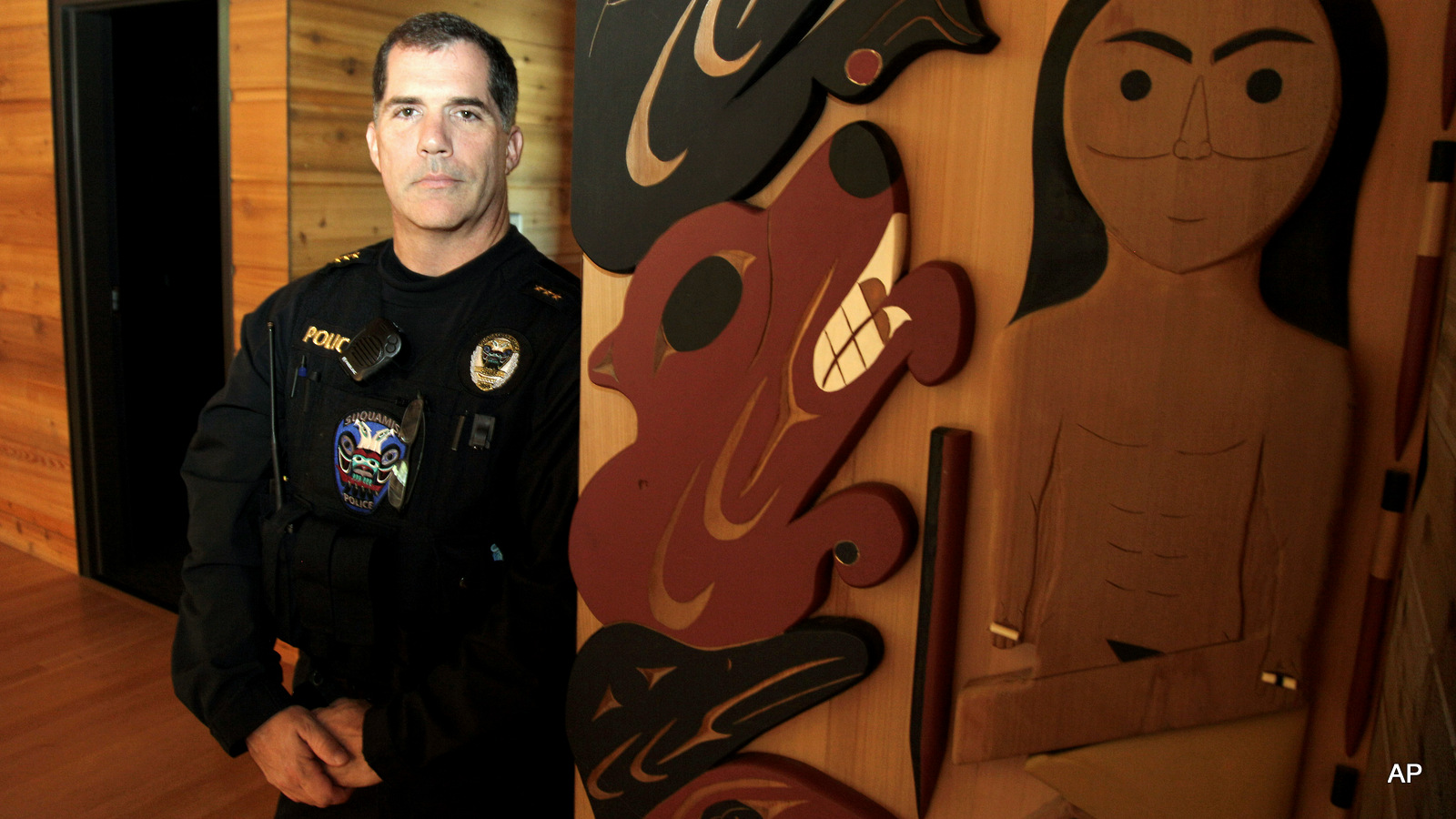

Mike Lasnier, Chief of the Suquamish Tribal Police, poses for a photo on the Suquamish Reservation in Washington state. Across the country, police, prosecutors and judges have been wrestling with the vexing question for decades: Who qualifies as an Indian when it comes to meting out justice for crimes on reservations?

Mike Lasnier, Chief of the Suquamish Tribal Police, poses for a photo on the Suquamish Reservation in Washington state. Across the country, police, prosecutors and judges have been wrestling with the vexing question for decades: Who qualifies as an Indian when it comes to meting out justice for crimes on reservations?

ALBERTA, Canada — Kainai police on the Blood Tribe Indian reserve went to a house in the Standoff village on March 20, and found the couple living there dead of an overdose of the street drug commonly known as Oxy80.

In a separate incident that same day, two others were found unconscious and rushed to the hospital, where they were treated for drug overdoses. Three community members were arrested and charged with drug trafficking and negligence causing death in connection with these cases.

Oxy80 is a street drug containing fentanyl, a highly addictive painkiller used in chronic pain management and as an anesthetic. Its effects are sometimes compared to heroin, and it’s described as being even more potent than morphine.

“The deaths were caused by fentanyl,” said Rick Tailfeathers, director of communications for the Blood Tribe. “It’s all over Alberta. We’ve had a hundred deaths over six months. Twenty-five of them were here on the reserve. That’s disproportionate. We have a population of 12,000 in Alberta’s population of 4 million.”

Trailfeathers says the tribal council is looking at other factors contributing to this trend and working in the people’s traditional ways to protect the community.

“We have the option to banish people from our reserve through council resolution,” he told MintPress News. “Any problem person can be brought into council and they vote. It’s been done before. It’s an option.”

In recent years a community member has been banished for committing sex crimes against children. They’ve also banished a non-member: a local man, who was allegedly robbing gravesites of weapons and beads. Though he was never officially charged, enough community members agreed that he should not be living or working in their territories. A third banishment was gang-related. After a gang leader tortured and killed someone, he was charged and imprisoned. When he was released, the tribe refused to allow him to return.

“In the old days, we banished people who harmed the tribe,” Tailfeathers said. “We’re a tight community. Banishment is a hard thing to do because there are relatives who don’t want a person to go.”

The three members currently facing drug charges will stand in a non-native court and face imprisonment. When released, they may need a letter of permission to return to the reserve, as it’s ultimately the community’s decision.

“In the old days there were no prisons,” Tailfeathers said. “Back in those days a person couldn’t easily survive alone against the elements, enemies or starvation. We’d survive as a group. We’d hunt in groups.”

He says the Hell’s Angels control the area drug trade and filter the drugs through small gangs on reserves, who sell it for the motorcycle club, which the U.S. Department of Justice recognizes as a crime syndicate. Some people involved in this drug trade are as young as 12 years old.

“There’s a lot of money to be made, especially on reserves suffering unemployment and people are on social service assistance,” he said. “Drugs are easy to get here here — just walk down the street. Hell’s Angels know this is a lucrative market.”

Traditional justice

The Blood Tribe’s community is behind a massive effort to educate people regarding the dangers of Oxy80.

“There’s an ambulance in the village, but we’re 20 miles from a hospital,” Tailfeathers said. “Doctors came up with an emergency kit to inject as an antidote to give us 45 minutes, long enough to get to the hospital. We have foot patrol who walk about day and night looking for people in trouble. Now they’re trained to inject this when they recognize its symptoms.”

The deaths affect the entire community, he says. The couple who died in March left behind two teenage children. An 18-year-old mother of a young daughter is also among those who have recently died of drug overdoses.

“When the couple died a meeting was called by council to deal with the grief,” he said. “A vigilante group wanted to get together to go to their house. We’re a small community. We knew who was dealing the drugs. It was an easy arrest for [tribal] police, who went to their house and found the drugs.”

Tailfeathers’ community is considering the drugs a symptom of a larger problem. “We’re looking at the causes,” he said. “Poverty has to be dealt with, a chance for a healthy future has to be found.

Indeed, banishment is an extreme measure to protect a community and its future that a growing number of tribes have been using in response to the rise of drug and alcohol abuse and violence. Being banished can mean a loss of health, housing and education benefits, Native rights to fishing, hunting and burial, and in some cases the cash payments from a casino. It can also mean homelessness.

Last year, in the Athabascan Indian village of Tanana, Alaska, the community of 250 expelled two men who threatened tribal members and contributed to the deaths of two Alaska state troopers.

Located on Yukon River, Tanana was a trading site until a century ago. Now a permanent community, it has a school, clinic and store but no connection to the highway and no law enforcement under its governance. State troopers must be flown in, and it often takes them days to arrive.

Arvin Kangas, a 58-year-old community member, drove into town and pointed a gun at the unarmed village public safety officer on April 30, 2014. The state troopers were called, and two officers were flown into Tanana the following day. During their attempt to arrest Kangas, his son Nathaniel shot and killed both officers.

The village voted to banish Kangas and another person who had assaulted tribal employees. While state troopers unofficially help to support any banishments, it’s traditionally up to councils protect the peace.

Ten years ago in Bellingham, Washington, the 3,000 members living on the Lummi Indian Nation reserve made the difficult decision to banish a member whose family struggled with alcohol and drugs. Several of the family members were jailed for dealing drugs, a decision the community made on hundreds of others cases in their effort to maintain traditional peaceful ways.

Lummi Nation Police Chief Ralph Long says the nation has a panel of community members who hear cases and decide if banishment is necessary.

“In order to come back, the offender must attend treatment, anger management, community service hours, have a mentor who is an elder and have committed no more offences,” Long told MintPress.

Depending on the case, they may also need to stand before the community and apologize.

The offender has five years to achieve their stated goals, then he or she submits documentation that those goals have been reached, and a citizen panel will also hear testimony before deciding if it’s sufficient.

“A lot of conditions set in place are the offender’s responsibility,” Long said. “It’s for those who want it. We have people who do want to come back. That’s why the standards are there. Those wanting to be side tracked won’t be back.”

The offender presents documentation of what has been achieved on the list in the past five years and explains to the panel why he or she should be allowed to come back.

“We have a justice system delegated to help them come back,” Long said. “We look at the paperwork and guide them through it. We want to hold people accountable and we want them to succeed.”

“Every tribe handles those things according to their custom,” said Ray Ramirez, director of communications for the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) in Boulder, Colorado.

Peacegivers keep the peace

In his 1997 article, “Strengthening Tribal Sovereignty Through Peacemaking: How the Anglo-American Legal Tradition Destroys Indigenous Societies,” Seneca Indian attorney Robert Porter explains:

“Indian nations are losing their sovereignty-that is, their ability to self-determine their own future and survive as distinct peoples-because they have lost or are losing their inherent ability to resolve the disputes that arise within them. Most indigenous communities today now rely upon formal court systems modeled after the Anglo-American legal system as their mechanism for resolving disputes within their territories.”

NARF’s Indigenous Peacemaking Initiative Project supports tribes’ efforts to bring back old customs instead of dealing with courts and jails.

“It’s a lot more effective than putting someone in front of a judge or behind bars,” Ramirez said.

Based on restoring relationships rather dealing with a hierarchy of punishments, it brings together the perpetrator, the victim and the lives they touch with values of respect and collective healing.

“An offense actually affects a lot of people,” Ramirez told MintPress. “It will affect the families of both the offender and the victim. In some cases the whole community has been affected, so we bring together all families and sometimes the elders. They come together to come up with a solution to make sure the problem never happens again.”

NARF facilitates re-creating the ancient circle used for restorative justice, where a safe place allows for all to be heard, people speak directly to each other, and consensus shapes the community.

Reservations that have their own tribal courts have also been incorporating traditional justice into the process. The 1,000 members of the Coquille Indian Tribe, whose ancestors have lived on the lower Coos Bay in Oregon for thousands of years, responded to modern-day problems with their heritage in 2005 by incorporating a resolution for Peacegivers into their judicial system

Peacegivers are chosen from among those the community trusts and respects to maintain the atmosphere of honoring the tribe’s values and promote healing. When there is an arrest, the court will appoint them to resolve disputes in a way that will integrate victims and perpetrators back into the community.

The meetings are confidential. Lawyers can participate in the peacegiving circle and Peacegivers give a report to the tribal court. They may testify in a court case if participants give their permission.

Peacegivers involve everyone they feel has been affected in a safe circle, where they are allowed to express emotions ranging from anger and terror to grieving. The focus is on the wellness of everyone in ways a court system does not allow.

When a young person is seen to be getting involved with drugs, the tribal council may offer to send him or her to a rehab program and help secure job opportunities once the program is finished. If, however, that person doesn’t want help, he or she will be banished.

Tribes may banish someone temporarily, offering an offender the chance to change and be welcomed back. Solutions may include bringing juveniles who are causing havoc into the wilderness with older people to teach them how their people survived on the land in the past.

“In turn, they’re learning their culture, they’re learning respect for earth, and once they understand that, respect comes for people,” Ramirez said.