TEMA, GHANA (Analysis) — The Argentine naval vessel Libertad embarked on its maiden voyage in 1961 and remains, to this day, a maritime and mechanical marvel. At 340 feet, it is one of the longest, heaviest, and yet fastest ships afloat — holding, at one time or another, several world speed records. With its classical windjammer design and clipper bow, it is the ninth naval vessel in Argentina to bear the name “Libertad” and is adorned with a wood-carved figurehead clothed in long, flowing robes to represent the idea of liberty.

The frigate continues to be used today as a training ship giving annual instruction to graduating naval cadets, and a goodwill ambassador that has traveled to some 500 ports in nearly 60 countries. Included among them was the western African nation of Ghana — where on September 2, 2012, a subsidiary of a Wall Street hedge fund ingloriously impounded the glorious vessel, after it won an injunction from a local court to seize the Libertad, stranding its 220 crew members.

The repossession, as it were, of a sovereign asset, was triggered by an American billionaire, Paul Singer — and the Cayman Islands subsidiary of his Wall Street hedge fund, Elliott Capital Management — in an attempt to collect a $1.6 billion debt from Argentina. At issue was the South American country’s debt restructuring, following a 2001 default on $100 billion in loans, that reduced bond payments to 30 cents on the dollar. Elliott Management was one of the few lenders that rejected the deal, preferring to dun Argentina for payment in full. The fund had been closely monitoring the Libertad’s journey, and waiting for it to dock in the port of a corporate-friendly country that would be willing to enforce the judgment against Argentina that Elliott Management’s lawyers had won in a U.S. federal court.

In a stinging rebuke to Ghana, the United Nations’ International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea ruled in December of that year that the Libertad had diplomatic immunity and its seizure was, therefore, illegal; Ghanaian authorities were ordered to release the military vessel immediately.

Clooney’s diagnosis

Writing in the March 14 issue of Foreign Affairs magazine, the Hollywood actor George Clooney and the human-rights activist John Prendergast identified corruption as one of sub-Saharan Africa’s greatest challenges and called for stiffer financial sanctions against kleptocratic leaders. The authors began thus:

In December 2013, competing factions of South Sudan’s ruling party plunged the country into a horrific civil war as they fought over the spoils of the world’s newest state. Now in its fourth year, the conflict has ravaged the economy, resulted in tens of thousands of deaths, brought hundreds of thousands to the brink of famine, and displaced more than four million people, making this Africa’s largest refugee crisis since the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

And yet, amid all the suffering, a small clique of government elites and their cronies inside and outside South Sudan have benefited financially from the fighting, siphoning off the country’s oil wealth and storing the money in their private bank accounts and in luxury real estate in neighboring countries.”

They concluded:

A comprehensive strategy of using financial pressure for peace and human rights in South Sudan and other African war zones would cost very little. But it would give African mediators and their supporters in Washington, London, and elsewhere leverage in peace negotiations.

It would put new wind in the sails of African anti-corruption and human rights activists, create real accountability for the mass theft of Africa’s resources, and finally begin to dismantle the system that incentivizes those in power to hijack the government for personal enrichment.

Without taking aggressive measures to go after the spoils that drive conflict in South Sudan and other African countries, it is difficult to imagine any future other than one of deepening repression, growing famine, and spiraling warfare.”

Mistaking symptoms for causes

At first glance, the millionaire actor-cum-Democratic party fundraiser from Kentucky and the former National Security Council bureaucrat might seem odd choices to diagnose what ails the world’s poorest and least developed continent — particularly considering the availability of nearly a billion Africans who live south of the Sahara who might have ideas of their own. And while the co-authors’ prescription is not altogether incorrect — corruption is indeed as ubiquitous in Africa as the baobab tree — their narrative misses a couple of key points.

First, there is no mention of the political context fueling public malfeasance — which rarely occurs in isolation and typically takes the form of bribery, influence-peddling or kickbacks. What Clooney and Prendergast fail to mention is whom, exactly, are Africa’s despots corrupt with?

Second, is African corruption the result of a neo-colonial political economy that historically required nothing more than a hole in the ground and a railroad to the sea, or is it merely attributable to some extra bone in Africans’ feet?

And third, what is corruption and who gets to define it?

Read more by Jon Jeter

- Low Energy, High Profits: How Privatizing Public Utilities Left Us All in the Dark

- Betraying the Bolivarian Revolution: Vichy Journalism at teleSUR English

- CNA and Retiring Head RoseAnn DeMoro Leave Labor in Critical Condition

- US Just Had a Black History Month, Now It Needs a White One

Ghana’s complicity with Wall Street banks to illegally seize the Libertad and hold it for what was essentially a king’s ransom trains a microscope on the molecular structure of an African leadership enthralled with global finance. To put only slightly too fine a point on it, African politicians today are more than willing to play the bagman to racketeering vulture capitalists like Singer.

Consider that Argentine authorities were quite aware that Singer’s Elliott Management was looking for an opportunity to seize the country’s assets to recoup its loans — that is why the country’s former president, Cristina Kirchner Fernandez, avoided using the presidential plane to fly to conferences and summits considered hostile. Argentina has no embassy in Ghana, and the two countries have not historically conducted much trade between them, but the Libertad had visited Ghana only at the invitation of its diplomatic officials.

As a result, Argentine officials said they had no idea that Ghana — a former British colony that staged the subcontinent’s first successful independence movement under the banner of the iconic resistance leader Kwame Nkrumah — would do Singer’s bidding. On the streets and in morning news broadcasts, Argentines commented on the irony of a country that had been brutalized by finance capital, agreeing to play ball with its torturers.

Horace G. Campbell — a professor of African studies and political science at Syracuse University, and currently on leave at the University of Ghana — told MintPress News:

Wall Street is at the heart of the illicit financial flows, and the corrupt African functionaries have to depend on reliable financial institutions outside of Africa to facilitate their corruption.”

Of Clooney, Campbell wrote: “[H]e obviously has not read the Panama Papers,” referring to the dossier that revealed a number of politicians around the world who stash ill-gotten gains in offshore bank accounts.

Western fingerprints all over African crime scenes

Indeed any forensic examination of African corruption would reveal Western fingerprints everywhere, from the financing of a ruinous civil war and exploitation of oil and diamond reserves in Angola, to the pillaging of mineral resources in Zambia.

The deepening impoverishment of South Africa’s black majority following the fall of apartheid in 1994 is a consequence of Western bankers pressuring Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress to renounce its redistributive macroeconomic plans in favor of laissez-faire policies. And NATO’s destruction of the most prosperous nation on the continent was at the behest of financiers who wanted to get their hands on Libya’s gas and oil reserves, as well as block Muammar al-Gaddafi’s plan to create a gold-backed African currency market that would have likely decreased the value of both the U.S. dollar and the Euro.

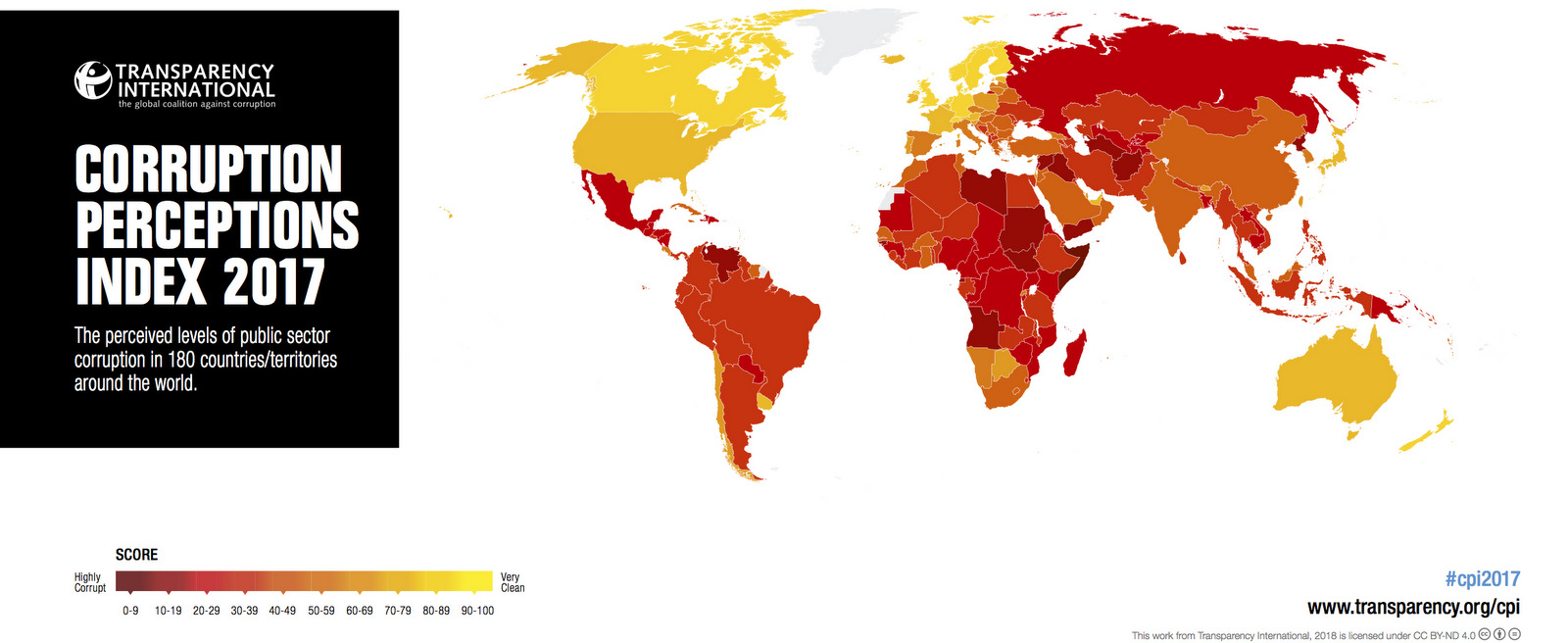

By ignoring the role that international financiers play in African corruption, Clooney is, perhaps inadvertently, repeating a dangerous trope that depicts the typical African leader as “half-devil, half-child.” Based on nothing more than collected perceptions, the NGO Transparency International continues to rank African nations at the top of its index of most corrupt nations and the U.S. near the bottom — in an era of subprime mortgages, weapons of mass destruction, enhanced interrogation techniques, and incarceration facilities at Cuba’s Guantanamo Bay and Iraq’s Abu-Ghraib.

Established in 2002 to investigate the most serious crimes, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has to date indicted only African leaders, leading several African nations to withdraw from the tribunal. After the ICC declined to indict former British Prime Minister Tony Blair for his involvement in the Iraq War, Gambia’s Information Minister Sheriff Bojang told the Guardian newspaper:

There are many Western countries, at least 30, that have committed heinous war crimes against independent sovereign states and their citizens since the creation of the ICC and not a single Western war criminal has been indicted.”

A 30-year-old Kenyan asylum seeker in Toronto told me recently:

Corruption is a big problem in Africa, but corruption is a byproduct of Western-styled capitalism that emphasizes the individual more than the community, as is traditional in African societies. Our leaders are responsible for their crimes against the people and should not be absolved, but it must be noted that they are merely mimicking the elites in America and London and Paris.”

Anti-corruption crusaders like Clooney, he said, might be wise to recall Oscar Wilde’s famous admonition that “all criticism is a form of autobiography.”

Watch | Stealing Africa – Why Poverty?

Top Photo | Argentina’s three-masted navy training tall ship ARA Libertad, which was seized on Oct. 2 as collateral for unpaid bonds dating from Argentina’s economic crisis a decade ago, sits docked at the port in Tema, outside Accra, in Ghana Friday, Dec. 14, 2012. (AP/Gabriela Barnuevo)

Jon Jeter is a published book author and two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist with more than 20 years of journalistic experience. He is a former Washington Post bureau chief and award-winning foreign correspondent on two continents, as well as a former radio and television producer for Chicago Public Media’s “This American Life.”