A key difference between maintaining homelessness and ending it in Washington state’s King County is a plan to offer the homeless keys to their own homes and access to support services.

“The American people have grown accustomed to modern-day homelessness,” said Michael Stoops, director of community organization for the National Coalition for the Homeless. “Unless we attack the systemic cause of homelessness, which is the lack of affordable housing, we will always have homelessness.”

King County, which includes the city of Seattle, is home to an estimated 3,000 homeless people. This population faces poverty, domestic abuse, disabilities and a lack of physical and mental health services.

When shelters reach their legal maximum capacities, they are forced to turn people away. This may be part of the reason why only about half of the county’s homeless stay in shelters, while the others live in their cars, abandoned buildings and parks.

Seattle and King County recently received $22.7 million in federal funding for homeless assistance. This funding will help support 70 community-based projects focused on the county’s “housing first” mission to provide housing and support services to individuals and families who are homeless or are at risk of homelessness.

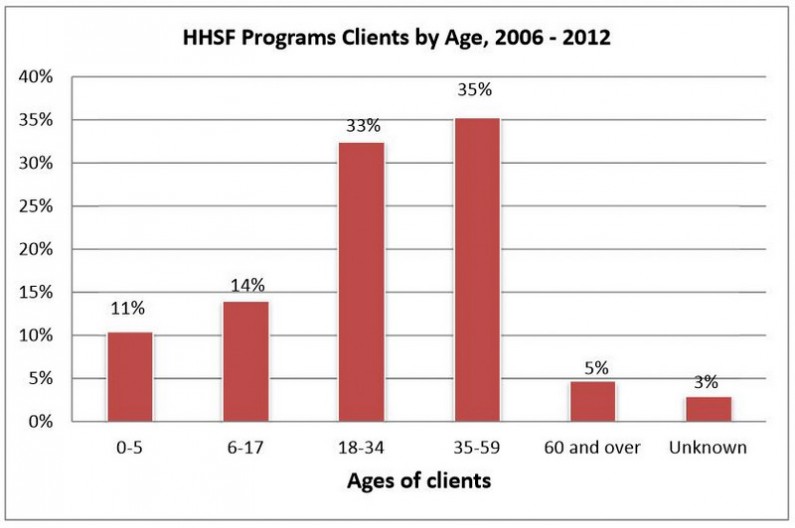

In 2005, the county’s council unanimously approved the adoption of “A Roof Over Every Bed,” a unique 10-year plan to end homelessness. With the involvement of the King County Department of Human Services and the Committee to End Homelessness, the plan established its own Homeless Housing and Services Fund, which serves about 2,400 households each year.

Case management and client assistance

“Those who are homeless want to get back on their feet and contribute to society, but that’s difficult to do if they don’t have safe, reliable shelter,” said Dow Constantine, co-chair of the Committee to End Homelessness Governing Board.

Since a significant percentage of the county’s homeless population lives in poverty and has poor housing records — for example, debts owed to previous landlords, evictions, poor credit histories and criminal records — service providers help enroll individuals or families into housing support programs that incorporate case management and client assistance to maintain housing stability.

“People have been able to get out of homelessness and stay out of homelessness,” Stoops told MintPress News of the housing first model. “Half of all homeless people just need a decent job or a cheap place to live. The other half need the support of social services.”

In 2009, the creation of the Landlord Liaison Project in King County facilitated coordination with landlords to make units available to homeless clients. Training is also available to inform landlords and social service providers about fair housing laws, as well as to provide clients with an understanding of budgeting, conflict and domestic violence support, and their roles and responsibilities as tenants.

Other accessible social services include job training, mental and medical health treatment and addiction counseling.

According to the Homeless Housing and Services Fund 2013 progress report, 91 percent of households enrolled in the program have maintained their permanent or non-time-limited housing for at least one year.

Cutting costs

More than half of homeless single adults in the United States struggle with mental illness, substance abuse and other chronic health issues. Issues like these have resulted in these adults repeatedly cycling through homeless shelters, emergency room visits, psychiatric hospitals and jails.

New York’s Common Ground says providing housing support to a homeless individual costs less than it does to maintain his or her life on the street. The cost of maintaining one mentally ill homeless person in New York City is $56,350, according to the program’s estimates, but it would cost just $24,190 to provide that person with housing and support services.

As Common Ground has found with its Street to Home program and as King County has found with its housing first model, homeless individuals and families can become stable, independent and productive members of their communities when they have access to permanent housing and support services.

Though these programs are both recording success and reducing the costs associated with homelessness, a greater national initiative and more funding are both still needed.

“The downside of the housing first model is that it’s not a fully implemented program because there’s not enough money that’s been appropriated by Congress,” said Stoops.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, Washington state was one of the top five states with the greatest drop in homelessness from 2007-2013. Homelessness dropped by 24 percent in Washington state in the five-year period. Though New York remains among the states with the lowest rates of homelessness, it saw one of the greatest increases in homelessness in 2007-2013.