A A jar holding waste water from hydraulic fracturing is held up to the light at a recycling site in Midland, Texas, Sept. 24, 2013. (AP/Pat Sullivan)

A A jar holding waste water from hydraulic fracturing is held up to the light at a recycling site in Midland, Texas, Sept. 24, 2013. (AP/Pat Sullivan)

WASHINGTON — The oil and gas sector made little progress over the past year in publicizing more details about how companies are dealing with environmental, social and market risks in the fast-expanding hydraulic fracturing industry, according to new rankings.

While a few companies made major gains, according to 35 disclosure metrics defined by a coalition of investor and environmental groups, the industry as a whole saw little change from the previous year. Of 30 major producers, no company scored more than 18 out of 35, prompting the researchers to again give the industry as a whole a “failing” mark on transparency.

Some of the sector’s largest companies did the worst, including Chevron Corp. and Exxon Mobil Corp., according to a report on the findings released in mid-December.

“Across the industry, companies are failing to provide investors and other key stakeholders with quantitative, play-by-play disclosure of operational impacts and best management practices,” the report states. “Existing company disclosures remain mostly qualitative and narrative, or focus anecdotally on just one or a few of their multiple [operations], making systematic comparisons across companies difficult.”

The “benchmarking” report was jointly produced by two leading sustainable asset-management groups, Green Century Capital Management and Boston Common Asset Management, as well as two public interest groups, As You Sow and the Investor Environmental Health Network. The study is the second of its kind, with the first coming out last year.

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, involves the injection of large quantities of water, sand and a secret mix of chemicals into vertical and horizontal wells, in order to break up and release tiny bubbles of natural gas held in certain rock formations. As that gas rushes to the surface it brings with it some dangerous greenhouse gases, thus potentially threatening both air and water quality.

As such, the report’s 35 indicators cover publicly reported company policies on dealing with air emissions and potential water pollution, as well as the waste and dangerous chemicals left over after a well is fracked. Researchers also took into account broader governance policies and how companies were responding to concerns expressed by communities located near drilling operations. This last issue proved to be particularly problematic.

“Companies still fail to disclose comprehensive systems for identifying community concerns and corporate responses,” the researchers found. “Although the number of companies that scored any points in this category increased to 13 from a mere six in 2013, companies continue to score worst on their disclosed policies and practices to the community impacts of their operations.”

While companies did improve their responses to issues such as traffic congestion around fracking operations, the report notes, “Still largely absent … are discussions by companies of which impacts are of greatest concern in the communities … and the companies’ specific practices to address those concerns.”

Localizing response

This resistance to policy changes continued despite a vastly expanded public and policy discussion on concerns around health and environmental impacts of natural gas fracking. In turn, those concerns and the broader public debate, alongside potential policy responses and broader unevenness in global energy markets, are increasingly worrying investors.

In particular, individual and institutional shareholders are more and more keen to ensure that the fossil fuel companies in which they’re investing are offering comprehensive disclosure of the risks the fracking industry may be facing from lawsuits, regulatory action or changes, and energy markets that have plunged in recent months. Investors also want to know what companies are doing to mitigate these risks and insulate their investments.

For these reasons, some investors say the lack of detailed, local-level reporting highlighted in the new report is particularly worrying, as is the apparent lack of substantive attention being paid to community concerns.

“Our analysis really focuses on localized reporting, given that lots of the risks to investors – water and air pollution, for instance – are at the local level, as are the risks of bans and moratoria,” Lucia von Reusner, a shareholder advocate at Green Century and a co-author of the new report, told MintPress.

“Yet the largest companies are continuing to rely on broad, sweeping policies and narrative reporting that doesn’t really address localized concerns. As investors we can only go on the information that is reported, and we have to assume that if a company isn’t reporting on impact and progress then it’s most likely not managing that particular risk – or, if it is, that the results are not worth reporting on.”

Of course, regulatory risks also come from the federal level. The federal government, for instance, is currently looking into strengthening restrictions on leakages of methane from natural gas wells. If taken, such action would aim to ameliorate not local but global impact, as methane is widely understood to be a particularly potent greenhouse gas – some 86 times worse than carbon dioxide over 20 years, von Reusner says.

“Methane was a big issue this year, so it’s really concerning that the fracking industry is not disclosing related policies and data. We found that only three companies reported on their methane leakage,” she noted.

“The possibility of federal regulation of methane is thus an important issue for investors, which is why we’re now asking companies to report on it. As investors, we want to know which companies are leading and which are lagging on this issue, so that when regulations come down we’ll know which companies will be most impacted.”

Undisclosed risk

Although the new rankings show relatively little cumulative progress, some companies say that last year’s report specifically motivated them toward pointed change around greater transparency and disclosure. The most noticeable change in the rankings, for instance, was the Australian extractives giant BHP Billiton, which jumped from near bottom to the highest score in just a year’s time.

“At BHP Billiton, our priority is to always operate hydraulic fracturing activities safely and in an environmentally responsible way and to report our performance openly,” a company spokesperson told MintPress. “The investor scorecard report issued last year gave a clear signal of where investors are seeking broader disclosure; we used that to help improve our public reporting this year, and we will continue to look for ways to improve.”

Green Century itself took last year’s report to heart, as well. Looking at what it saw as significant undisclosed risk in the firms in its portfolio, the group decided to divest all of its holdings in oil and gas companies, to become the United States’ first fossil fuel-free fund.

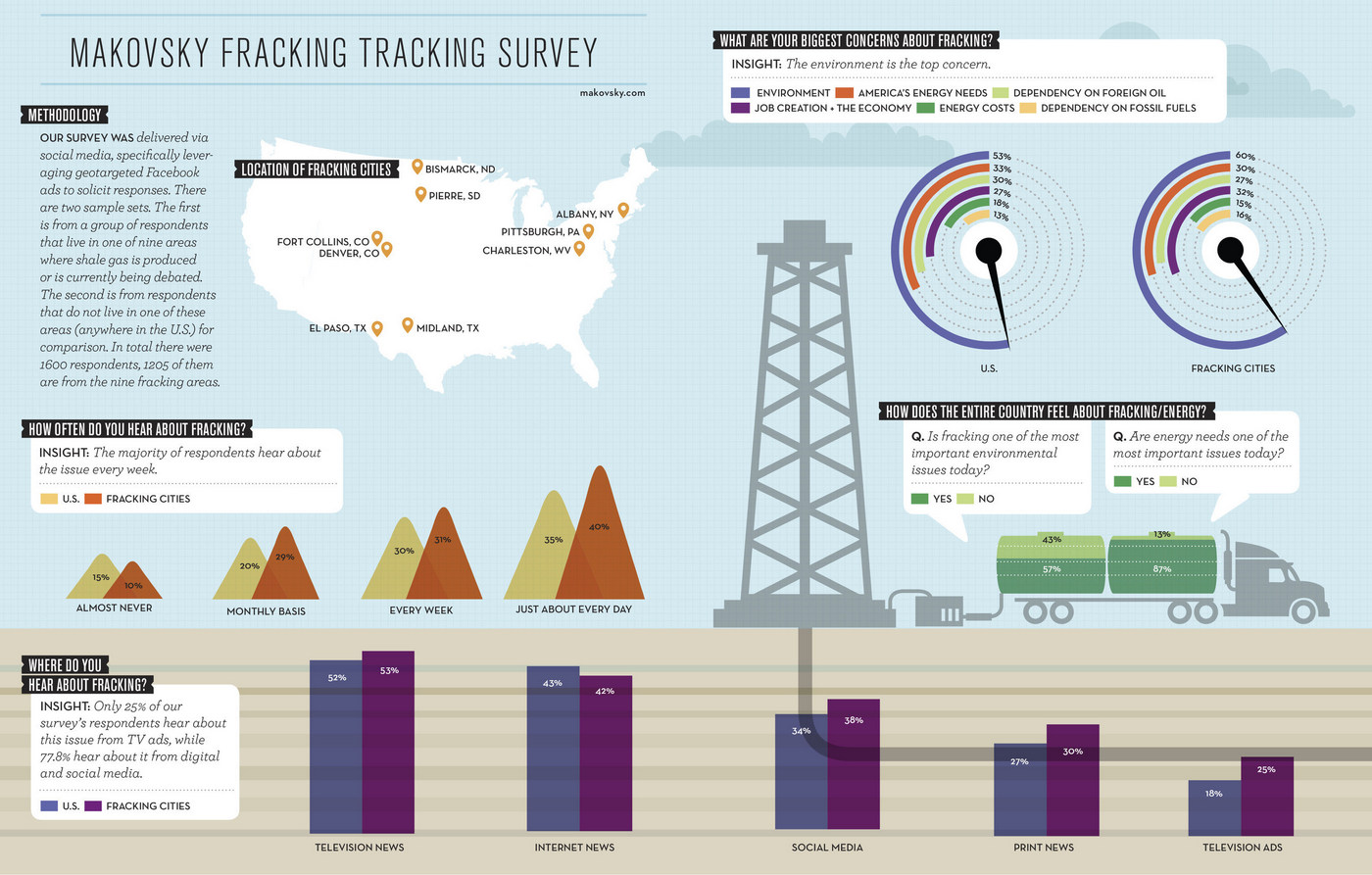

Survey data in the report shows that 57% of U.S. consumers believe that fracking is one of the three most important environmental issues today. Photo: PRNews/Makovsky & Company

The past year saw a significant strengthening of the public discussion around divestment, with increasing pressure being placed on state pension funds and university endowments to move away from investments in the oil and gas industry, particularly coal companies. Stanford University and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, for instance, made major such commitments this year, while Yale and others are reportedly considering the issue.

“The most dramatic shift of 2014 was the realization that the [energy] market is going to change. People used to think that the use of fossil fuels could continue unchanged for the next 20 years, but there’s now broad understanding that window is closing,” Jamie Henn, the co-founder of 350.org, an advocacy group that has been a key supporter of divestment, told MintPress.

“Today, this affects even those who, for political or other reasons, don’t want to say they’re open to divesting – nobody’s doubling down on coal. Even the Bank of England says it’s going to take carbon risk onboard, and that’s a sea change.”

Henn suggests that the recent downturn in global oil and gas prices has underscored longstanding concerns about the economic models being followed by extractive companies operating in the new gas market. With the season for shareholder meetings approaching, Henn says he expects investors will increase pressure on companies to discuss these and related risks in greater detail.

“These systems move slowly, but you can hear a new tone in the conversation among investors,” he said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if that plays out in very pointed questions to the natural gas industry during this cycle.”