The US and its European allies have coordinated the largest collective expulsion of Russian diplomats in history. Russia has promised to retaliate in kind. Yet despite the sense of certainty around Russian culpability in the Salisbury incident, questions remain around the state of the available evidence.

As contradictory narratives proliferate amidst conflicting Western and Russian government statements and media reports, a clearer picture of the secret history of the nerve agent used in the Salisbury poisonings is emerging.

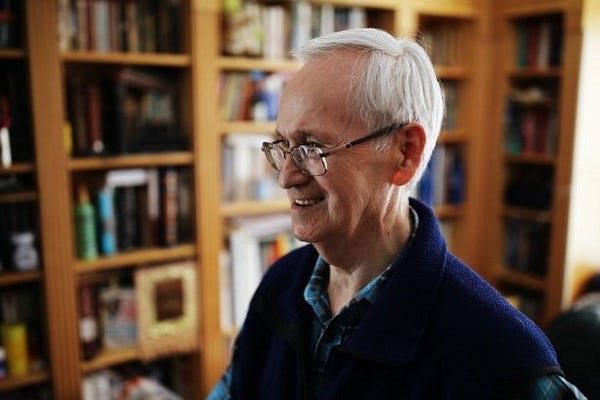

In an exclusive interview with INSURGE, a former senior official at the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) from 1993 to 2006, Dr Ralf Trapp, said that at this stage there is no conclusive evidence that Russia was the source of the nerve agent used in Salisbury. He pointed to compelling evidence that Russia did run a secret research programme to create Novichok-type nerve agents — and strongly criticised Russia’s denials of that programme. While justifying grounds for suspicion, there is as yet no decisive proof that Russia retained such a Novichok programme or capability today, he said.

In our previous story, INSURGE raised a range of questions and problems with the British government’s approach to the crisis. Dr. Trapp’s interview resolves some of these issues while raising new and alarming questions.

His insights are likely to be damaging to both the Russian and British government positions. The British government has insisted that its identification of the nerve agent points squarely and inevitably to Russia alone, even as Russian officials have insisted they have never run a programme to create what the UK had identified as ‘Novichok’.

Both these claims are flawed.

‘No data’ proving a Russian Novichok capability

On the one hand, Dr Trapp dismissed Russia’s ongoing official denials of any involvement in a Novichok-type nerve agent research programme. These denials, he said, are inconsistent with Russian government past positions and credible statements by Russian scientists involved with the programme.

On the other, Dr Trapp pointed out that the existence of a Novichok programme in Russia has never been technically “corroborated”, and confirmed that numerous Western states will have “re-engineered” the nerve agent for defensive research purposes.

Asked whether Prime Minister Theresa May’s claim that the chemical identification of Novichok in Salisbury can only lead to two possibilities, both revolving around Russian culpabability, Dr. Trapp conceded: “No there are other theoretical possibilities” before suggesting that “it would depend on what else the UK knows and has not yet made public.”

Read more by Nafeez Ahmed

- UK Sought Foreign Policy Advice From Cambridge Analytica Trump Team

- Britain Is Manufacturing A Nerve Agent Case for ‘Action’ Against Russia

- US Army Docs: Plan to ‘Dethrone’ Putin for Oil Pipelines May Provoke WW3

- New Study by Ex-Chief of BP-Acquired Solar Giant Sees Renewable Energy Revolution on the Horizon

He added that he “can’t immediately see motive or opportunity” for other parties, “except for the UK as suggested by Russia” — a notion which, he emphasised, “I don’t consider credible at all.”

According to Dr Trapp, the name of the secret Russian nerve agent programme in question was ‘Foliant’, and there may have been similar programmes run by the FSB, Russia’s domestic service.

“I have no information about whether Russia continued the programme after the mid-1990s,” said Trapp, “but would not exclude the possibility that small amounts of what could be ‘explained away’ as materials needed in protective research have been retained or newly synthesized. But again — no actual data on this.”

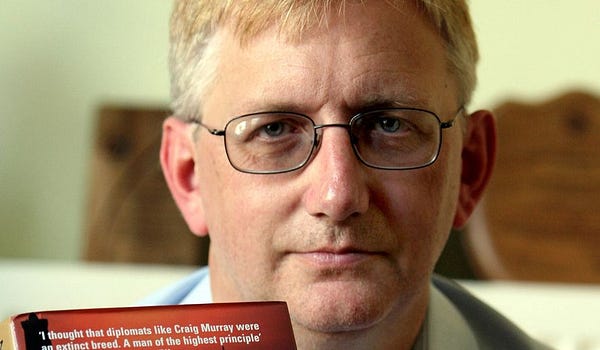

The lack of “actual data” for the British government’s case has been most prominently criticised by Craig Murray, previously a UK ambassador to Uzbekistan and former career Foreign Office (FCO) diplomat.

Murray revealed, citing his own FCO sources, that the government was using a consistent phrase to describe the nerve agent identified in Salisbury — “of a type developed by Russia”. This peculiar choice of phrase, he said, was because although the chemical structure may be the same as the type of nerve agent originally developed by Russia decades ago, there was no proof that the agent used in Salisbury had actually been manufactured inside Russia – leaving the possibility open that other parties may have been involved.

Russia did run a secret nerve agent programme, but it wasn’t called ‘Novichok’

That phrase carefully decided on by the FCO — “of a type developed by Russia” — has been replicated not only by the UK but by its allies in official statement after official statement. For Murray, this illustrates a concerted PR offensive to conceal the lack of chemical evidence that the nerve agent was created by Russia.

Though the British government appears to be obfuscating the degree of uncertainty that remains on this issue, the Russian government has also been decidedly economical with the truth.

The ‘Novichok’ programme was first revealed in 1992 by Dr. Vil Mirzayanov, a former chemist at the State Union Scientific Research Institute of Organic Chemistry and Technology (GSNIIOKhT).

Mirzayanov’s initial reports on ‘Novichok’ nerve agents concerned the ecological damage of the Soviet CW programme. He later revealed that these concerns related to a much wider ranging nerve agent programme.

Some of his claims have been recently corroborated to Russian state media by Professor Leonard Rink, a Russian chemist who admitted that he ran the programme in its later stages.

When asked whether he was involved with creating “what the British authorities call ‘Novichok’”, Rink replied: “Yes. This was the basis of my doctoral dissertation.” He confirmed that a large group of specialists in Shikhany and Moscow worked on the programme for years before they “finally achieved very good results.”

However, Professor Rink denied that there was any programme for the creation of chemical weapons called ‘Novichok’:

“Programmes for the development of chemical munitions existed, but not with this name. After any program was completed, it was handed over to the military, and they already had decided the name… There was no such separately taken substance called ‘Novichok’ and there was no development project with this name. Rather this was simply a system of coding and registration. It is therefore absurd to talk about the formula for ‘Novichok’ under a project of the same name.”

Rink confirmed that Mirzayanov had knowledge of the secretive Russian nerve agent programme, but denied that he was involved in creating it.

Rink’s assertion that Mirzayanov had no role in actually creating the nerve agent casts some of his claims into doubt, as Mirzayanov has repeatedly told various news agencies that he was directly involved in the relevant experiments.

Another Russian scientist, Vladimir Uglev, who also led on the nerve agent programme at GSNIIOKhT, criticized the OPCW in an interview with The Bell for failing to take action on their reports to the agency about the Russian nerve agent programme:

Why did the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) under the United Nations, if one finds their minutes from their meetings to be true, fail three times to find proof of production of this agent (searches began after the publication of Mirzayanov’s book in 2008)?

– It’s impossible to find a black button in a dark room. Moreover, the cat simply wasn’t there, because there wasn’t any production in the USSR, and Russia then was preoccupied with other things. The fact that the OPCW totally ignored our mutual statement with Mirzayanov in 1993 about the existence of agents of chemical warfare in Russia was a gross violation of the (Chemical Weapons) Convention, as signatory countries to the Convention are required to report the development of new substances, the most powerful of which are agents of chemical warfare.”

According to the Clingandael Institute, the US did not address its concerns about Russia’s undeclared Novichok capability through the OPCW: “The US decided to address these concerns through bilateral channels, rather than directly engaging formal OPCW mechanisms.” (p. 19)

Other states have ‘re-engineered’ Novichok agents for legitimate research purposes

Dr. Trapp’s analysis throws further light on the murky details of what Russian and Western governments know about the nerve agent that was used on Sergei and Yulia Skripal. His last post at the OPCW was Secretary of its Scientific Advisory Board. Since 2006, he has been a consultant on disarmament of chemical and biological weapons for the European Commission and several UN agencies.

Dr. Trapp confirmed that at least some Western countries “would have done their own research to be able to characterise these chemicals and be able to identify them by chemical analysis should they ever be used. That is perfectly legitimate under the CWC, which allows, for good reasons, countries to continue work in chemical protection, to acquire, synthesise and investigate toxic and precursor chemicals to this end, and to work on such issues as detection, identification, protection and medical countermeasures, decontamination and other technical aspects of protection.”

Asked if Mirzayanov’s claims had ever been corroborated, Trapp said that they had been “verified in a legal sense: not corroborated.”

Referring to Russian efforts to prosecute Mirzayanov for divulging state secrets when he first criticised the Soviet CW programme, Trapp added that:

As the original affair in Russia to an extent was played out in public, Western secret services will surely have picked up on that at the time, and some labs will have worked on ‘re-engineering’ these types of chemicals to see whether the claims could be true and to have data on these agents in their reference libraries.”

Dr Trapp explained that the primary reason the OPCW does not hold any information on Novichok is because it has not been declared by any state party under the CWC, largely due to fears about proliferation risks:

“It is my understanding that Novichoks have indeed not been declared as part of a CW stockpile or past CW production programme by any state party,” he said.

Assuming that the declarations essentially have been complete and honest, that would mean that no chemical weapons using Novichoks have been stockpiled by any state party when they became members of the OPCW. The Novichok issue came up several times in the OPCW Scientific Advisory Board, as a question of whether these chemicals or their precursors should be included in the CWC control lists — the ‘Schedules’; however state parties were not ready to include such chemicals, largely because of concerns about the potential proliferation risks related to critical CW knowledge leaking into the public domain and associated risks such as with regard to misuse of such data by non-state actors or rogue states.”

He noted that Iran had provided some information on its own Novichok experiments to the OPCW:

Some of the relevant chemicals also came to the fore when Iran submitted the analytical data of some of these chemicals for validation and possible inclusion into the OPCW analytical database used in routine verification.”

An article in Spectroscopy Now from January 2017 described how Iranian scientists had “synthesised five ‘Novichok’ agents, along with four deuterated analogues.” The “detailed mass spectral data” obtained from these experiments “have been added to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons’ Central Analytical Database (OCAD). It is important that such databases are as comprehensive as possible so that unusual chemical weapons can be unambiguously detected.”

CWC declaration rules mean Russia might still have a Novichok capability

Complicating matters further are rules around declaring chemical weapons. Last year, the OPCW declared that it had verified the complete destruction of Russia’s chemical weapons programmes.

But Russia’s failure to declare its ‘Foliant’ programme, under which the nerve agents called ‘Novichoks’ were researched, raises questions about whether those programmes were destroyed. As they were never declared, it is possible that some semblance of them still exists today. But it is also possible that they were indeed destroyed, and that today no such programmes or capability exist.

There is no firm data either way:

If these chemicals, the CW agents as well as their precursors, were actually in a CW stockpile when a state joined the CWC, they were declarable in great detail. My understanding is there were no Russian stockpiles of actual Novichok weapons in 1998. When a state had produced them, agent or precursors, as chemical weapons in the past, the respective production facilities, too, are declarable (including the chemicals and amounts produced) — Russia did not declare such facilities but it is likely they considered them part of the development programme. If these chemicals had been part of a CW development programme, on the other hand, the facilities, laboratories, test ranges etc. used ‘primarily’ for the development of such chemical weapons also must be declared, but the requirements are less stringently defined in the CWC — ‘primarily’ is open to interpretation and states have never been able to agree on a common understanding of how this term should be interpreted. There is no rigid format for whether or not the chemicals under development and chemical processes involved in their manufacturing needed to be declared. All that is legally required is a description of the ‘location, nature and general scope of activities’ of the facility. States parties have taken very different views on how transparent they should be under this formula and my understanding is that Russia did not include details on its novichok development work in its declaration of former CW development facilities.”

Dr. Trapp suggested, therefore, that while Russia’s official denials about the Novichok programme may well be technically correct, they are misleading because Russia privately admitted to running its nerve agent research in bilateral communications with the US:

As for Russia, I would take their statements very literally, exactly as they have been put on record. Russia, true, has never publically admitted it had worked on these chemicals as part of its CW programme. The programme was not called ‘Novichoks’ — its code name was ‘foliant’ — and the Novichok term for the chemicals of interest probably had no formal standing — the agents had codenames.”

Bilateral meetings between the US and Russia did provide confirmation of the programme, however, in the context of the Wyoming Agreement and the Bilateral Destruction Agreement. The latter “never entered into force but the data exchanges and some site visits and clarification meetings were conducted between the two countries,” said Dr Trapp.

“In those discussions, the Russians never disputed the factual claims by Mirzayanov, including the research and development work on Novichoks, the agents involved etc. They merely disagreed with the US interpretation as to what, if any, of this would be declarable under the agreed rules of data exchange, which also were reflected in the rules of the CWC declaration system and ambiguities regarding what needed to be declared under development of CW.”

OPCW will investigate nerve agent used in Salisbury

While Russia’s reticence on its ‘Foliant’ research programme vindicates suspicions of its role in the Salisbury attack, there is no firm evidence yet that the agent used proves Russia’s culpability. The OPCW may, however, be able to provide independent confirmation of the agent and its origin of manufacture:

“What is going on at the moment is a mission under a more general mandate of OPCW to provide technical assistance and evaluation support to the UK… Whatever comes out of this work will be technical in nature, it will certainly confirm the agent used, and there may be forensic information that may help establish what method of synthesis had been used, how the material was administered or disseminated, and what kind of chemical signatures there are that would allow to establish the composition of the tactical mixture used — that is, chemicals used to formulate the agent into tactical mixtures — e.g. stabilisers, chemicals that modify/moderate certain physical properties etc. If the OPCW, or the UK, would have access to the raw materials used in a suspected lab, they also would be able to establish whether or not the agent came from those specific raw materials, based on characteristic signatures such as certain impurities, or the stable isotope ratio of certain chemical elements of the agents themselves. This can be done down to the individual batch of chemical synthesis or raw material used.”

After the British government accused Russia of involvement in the Salisbury attack, the Russian government requested a sample of the agent used. This would have allowed the Russians to conduct its own such tests and, potentially, publish the findings. The UK, however, declined to provide a sample.

Leonard Rink, one of the Russian scientists who confirmed the existence of the ‘Foliant’ programme contrary to official Russian denials, has argued that the UK’s refusal to provide the sample suggests it does not exclusively point to Russian origin:

For any country with weapons of mass destruction — the UK, the US, China and all developed countries — any country with at least some chemistry would have zero problems creating this kind of weapon. Why aren’t the British providing a sample to Moscow? Because no matter how hard [British] specialists try, a technology will always differ somewhat. This is its unique signature. It will be immediately clear that it is not a Russian-made technology.”

In summary, Dr Trapp’s interview unearths compelling evidence that Russia was indeed working on a CW programme, identified by Mirzayanov as ‘Novichok’, but not formally identified internally by that name. This raises legitimate questions regarding Russia’s declaration obligations under the CWC, whose import is heightened in light of Russia’s blanket denials. In the past, Russia claimed to have destroyed its past Novichok-capability. Trapp’s information shows that while Russia may well have retained a Novichok-capability which it refused to declare, there is as yet no direct evidence of this. And yet, while we should be wary of Russian disinformation, Trapp’s comments also reinforce questions as to why the British government is asserting absolute certainty on Russian culpability, citing scientific evidence about the nerve agent used in Salisbury — when that evidence is technically compatible with other scenarios.

All this leaves more questions than answers, but perhaps the most pertinent is this: In the absence of such evidence, is it wise for the West to rapidly escalate diplomatic tensions with Russia?

Top Photo | Police officers guard a cordon around a police tent covering a supermarket car park pay machine near the spot where former Russian double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter were found critically ill following exposure to the Russian-developed nerve agent Novichok in Salisbury, England, Tuesday, March 13, 2018. The use of Russian-developed nerve agent Novichok to poison ex-spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter makes it “highly likely” that Russia was involved, British Prime Minister Theresa May said Monday. Novichok refers to a class of nerve agents developed in the Soviet Union near the end of the Cold War. (AP Photo/Matt Dunham)

This story was 100% reader-funded. Please support INSURGE Intelligence for as little as $1 a month, and share widely.

Dr. Nafeez Ahmed is the founding editor of INSURGE intelligence. Nafeez is a 16-year investigative journalist, formerly of The Guardian where he reported on the geopolitics of social, economic and environmental crises. Nafeez reports on ‘global system change’ for VICE’s Motherboard, and on regional geopolitics for Middle East Eye. He has bylines in The Independent on Sunday, The Independent, The Scotsman, Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, Foreign Policy, The Atlantic, Quartz, New York Observer, The New Statesman, Prospect, Le Monde diplomatique, among other places. He has twice won the Project Censored Award for his investigative reporting; twice been featured in the Evening Standard’s top 1,000 list of most influential Londoners; and won the Naples Prize, Italy’s most prestigious literary award created by the President of the Republic. Nafeez is also a widely-published and cited interdisciplinary academic applying complex systems analysis to ecological and political violence.