BRUSSELS — On April 24, the Republic of the Marshall Islands filed unprecedented lawsuits with the International Court of Justice in The Hague, Netherlands, to hold the world’s nine nuclear-armed states — the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia, China, France, Israel, India, Pakistan and North Korea — accountable for flagrant violations of international law with respect to their nuclear disarmament obligations.

Some might wonder why would a tiny state somewhere in the middle of the Pacific between Hawaii and Guam decide to target the nine most powerful states in the world? One reasons is that the Republic of the Marshall Islands knows firsthand the horrors and consequences of living in a world with nuclear weapons: between 1946 and 1958, the U.S. used it as a testing ground for its nuclear weapons.

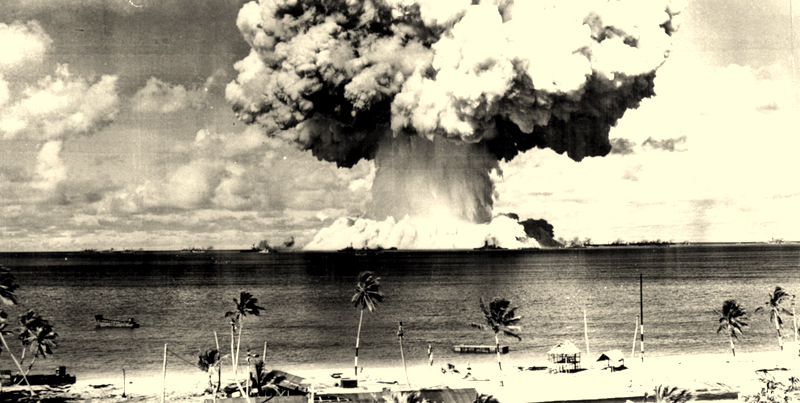

During this 12-year period, 67 nuclear tests were conducted on Bikini and Enewetak atolls and adjacent regions. The most significant single contaminating event was the Castle Bravo test, conducted on March 1, 1954 at Bikini Atoll. Prior to the testing, the inhabitants of Bikini and Enewetak were sent to Rongerik Atoll. When they left their homes, they though they would be able to return after a short time.

But the designers of Castle Bravo made a grave error in calculating the yield of the device. They expected the yield to be roughly 5 to 6 megatons, but it produced an explosive yield of 15 megatons, making it 1,000 times more powerful than the U.S. nuclear weapons used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Not only did the test leave Bikini and Enewak uninhabitable, it also led to critical fallout in the Rongelap, Rongerik, Alinginea and Utirik atolls.

Evacuations organized by the U.S. were too slow to limit the lethal doses of radiation that inhabitants were submitted to. Additionally, Rongerik — where the Bikinians had been sent — had inadequate supplies of water and food, as the administration had only sent several weeks’ worth of food. As a result, the Bikinians began to suffer from starvation and fish poisoning due to the lack of edible fish in the lagoon. Within two months after their arrival, they begged U.S. officials to move them back to Bikini.

It was not possible for them to return home. Realizing this, they choose to live on Kili Island, a small island one-sixth the size of their original home. In the early 1970s, U.S. government scientists declared Bikini safe for resettlement, and some residents were allowed to return. They were removed again in 1978 after ingesting high levels of radiation from eating foods grown on the former nuclear test site.

Bikini islanders and their descendants have lived in exile ever since. The radioactive fallout continues to leave some of the islands uninhabitable. An estimated 665 inhabitants of the Marshall Islands were overexposed to radiation. The inhabitants of contaminated atolls have experienced numerous health problems, including birth defects, and the Marshall Islands still has one of the highest cancer rates in the Pacific.

“Our people have suffered the catastrophic and irreparable damage of these weapons and we vow to fight so that no one else will ever again experience these atrocities,” said Marshall Islands Foreign Minister Tony de Brum. “The continued existence of nuclear weapons and the terrible risk they pose to the world threaten us all,” he added.

The Marshall Islands is not seeking compensation for the damages done by the American testing, though. Its goal is much wider and more ambitious than that. Instead, it aims to obtain from an international court a clear message that tells the world’s nine nuclear nations in no uncertain terms that they need to fully meet their international nuclear disarmament obligations.

In other words, this issue extends well beyond the estimated 70,000 inhabitants of the Marshall Islands.

A pledge to disarm

To understand the true nature of the legal actions being taken by the Marshall Islands now, one must first look back. In 1968, the five nuclear powers at the time — the U.S., the U.K., France, China and the Soviet Union — and several non-nuclear countries reached an agreement to stem the spread of nuclear technology. The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, which entered into force in 1970, sought to stop the further spread of nuclear weapons beyond the original five.

The agreement went further, though. Article VI of the treaty states that “each of the parties to the treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to the cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

In other words, the treaty rested on a kind of deal: non-nuclear countries committed not to acquiring nuclear weapons and were guaranteed access to peaceful civilian nuclear technology under safeguards; and in exchange, the five original nuclear weapons states committed to pursuing nuclear disarmament. To date, 190 countries have become party to the treaty and 93 have signed it.

Under the treaty, nuclear weapons countries are supposed to work toward the cessation of the nuclear arms race and toward nuclear disarmament. This was expressed in even clearer terms in 1996 by the International Court of Justice — the same court the Marshall Islands has now seized upon — when it issued an advisory opinion stating that the use and threat of use of nuclear weapons violate the principles of international law.

“There exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament is all aspects under strict and effective international control,” the 1996 International Court of Justice opinion reads.

The five original nuclear weapons states have always been open to charges of hypocrisy. Behind the rhetoric of disarmament, they have tried everything to prevent second-tier powers from obtaining nuclear arms while clinging to their own arsenals. Not only do they not show any intention of disarming, in many cases, they are also upgrading.

The Marshall Islands case draws attention to the fact that rather than scrapping warheads, the countries named are currently in the process of modernizing their nuclear weapons, which it considers as a clear violation of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The case against the U.S. alleges that “the Respondent has been actively upgrading, modernizing and improving its nuclear arsenal.”

According to the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, a U.S.-based civil society organization, the U.S. plans to spend an estimated $1 trillion on nuclear weapons in the next three decades, and it currently possesses nearly half of the world’s 17,300 warheads.

The Marshall Islands is raising a far-reaching and fundamental question about nuclear weapons that concerns all of humanity. “This is one of the most fundamental moral and legal questions of our time. We must ask why these leaders continue to break their promises and put their citizens and the world at the risk of horrific devastation,” said South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

“Nuclear weapons threaten everyone and everything we love and treasure. They threaten civilization and the human species. After 46 years with no negotiations in sight, it is time to end this madness,”

said David Krieger, president of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, which actively supports the lawsuits. “The Marshall Islands is saying enough is enough. It is taking a bold and courageous stand on behalf of all humanity, and we at the Foundation, are proud to stand by their side.”

Tough legal obstacles

Some world leaders, international non-governmental organizations, well-known experts and Nobel Peace Prize laureates — including former President of Costa Rica Oscar Arias, Iranian human rights lawyer Shirin Ebadi, Argentinian human rights activist Adolfo Perez Esquivel — have declared strong support for the lawsuits and denounced nuclear weapons.

Despite this support, the lawsuits face a number of tough legal obstacles. First, four of the nuclear powers being sued by the Marshall Islands are not signatories to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. India, Pakistan, North Korea and Israel — which has never publicly admitted to having nuclear weapons — all acquired their nuclear weapons well after the treaty was created.

In addition to showing the treaty’s relative ineffectiveness, this also prompts the question about to what extent these countries can be bound by the provisions of a treaty they have not signed. The Marshall Islands and the international legal team — which is working pro bono — believe the obligations enshrined in Article VI of the treaty “are not merely treaty obligations; they also exist separately under customary international law,” according to the lawsuits. The four countries could, therefore, be linked by international customary law, which is binding for all states, regardless of whether they’ve signed a treaty.

Another issue is that of the nine states being sued in the International Court of Justice, only three — the U.K., India and Pakistan — accept its jurisdiction. The Marshall Islands is calling on the other six states to accept the court’s jurisdiction in this particular case — something that may prove difficult.

So far, the U.S. government’s only reaction has been a State Department statement saying that it was examining the lawsuits filed by the Marshall Islands. In the statement, the State Department defends the country’s record on disarmament. “We have a proven track record of pursuing a consistent, step-by-step approach to nuclear disarmament – the most recent example being the New START Treaty,” it said, referring to a 2010 nuclear arms reduction pact with Russia.

The lawsuits are unlikely to end in any country being compelled to disarm, but they will at least expose the hypocrisy of big nuclear powers claiming to be committed to multilateral disarmament initiatives. These countries like to invoke international law to argue against other countries like Iran having access to nuclear weapons — which is prohibited by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty — or even nuclear civilian power — which, under safeguards, is not prohibited — but they have a convenient and systematic tendency to forget about the other part of the deal laid out in the framework of the treaty: their own disarmament.