John Bolton’s March 22 appointment-by-tweet as President Donald Trump’s national security adviser has given “March Madness” a new and ominous meaning. There is less than a week left to batten down the hatches before Bolton makes U.S. foreign policy worse that it already is.

During a recent interview with The Intercept’s Jeremy Scahill (minutes 35 to 51) I mentioned that Bolton fits seamlessly into a group of take-no-prisoners zealots once widely known in Washington circles as “the crazies,” and now more commonly referred to as “neocons.”

Beginning in the 1970s, “the crazies” sobriquet was applied to Cold Warriors hell bent on bashing Russians, Chinese, Arabs — anyone who challenged U.S. “exceptionalism” (read hegemony). More to the point, I told Scahill that President (and former CIA Director) George H. W. Bush was among those using the term freely, since it seemed so apt. I have been challenged to prove it.

I don’t make stuff up. And with the appointment of the certifiable Bolton, the “the crazies” have become far more than an historical footnote. Rather, the crucible that Bush-41 and other reasonably moderate policymakers endured at their hands give the experience major relevance today. Thus, I am persuaded it would be best not to ask people simply to take my word for it when I refer to “the crazies,” their significance, and the differing attitudes the two Bushes had toward them.

George H. W. Bush and I had a longstanding professional and, later, cordial relationship. For many years after he stopped being president, we stayed in touch — mostly by letter. This is the first time I have chosen to share any of our personal correspondence. I do so not only because of the ominous importance of Bolton’s appointment, but also because I am virtually certain the elder Bush would want me to.

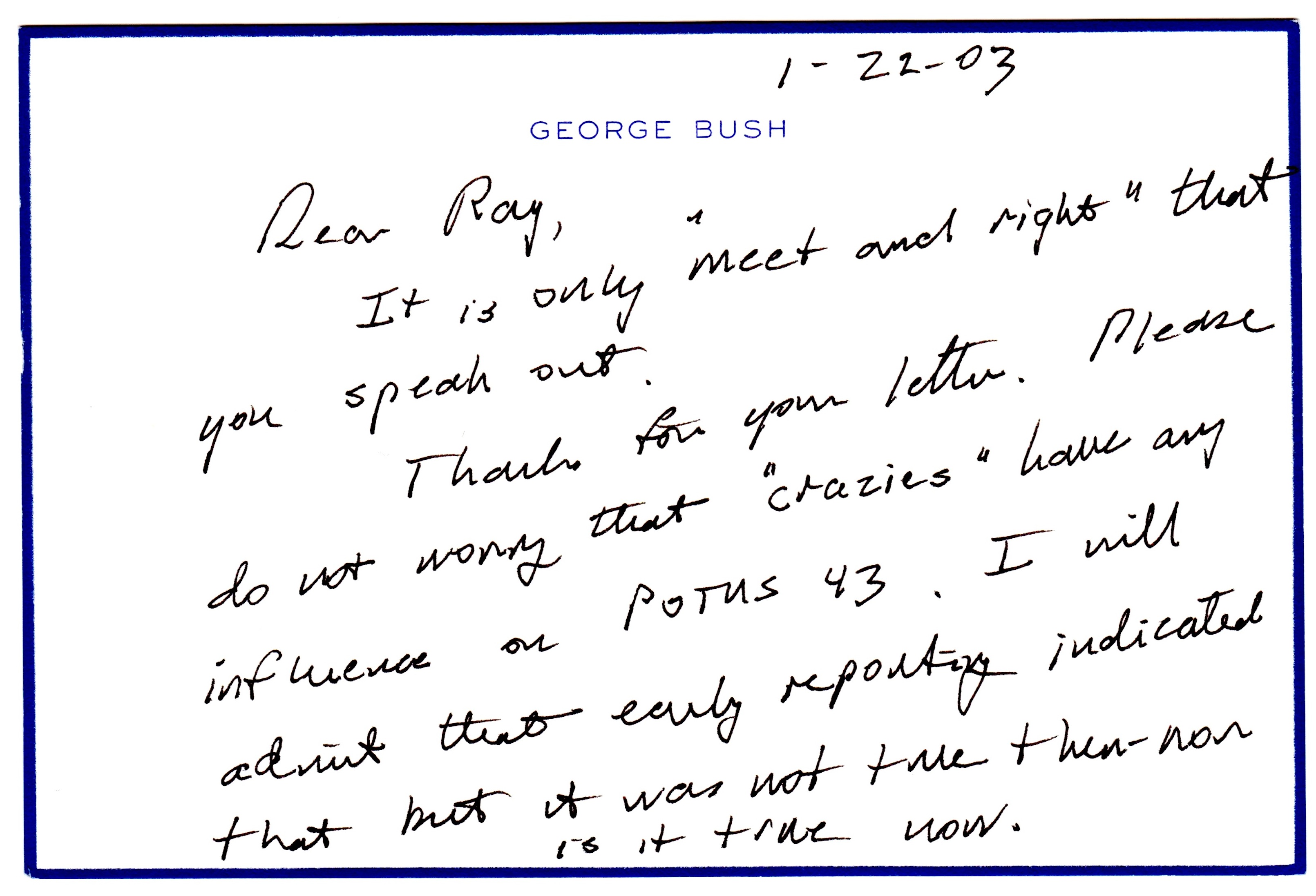

Scanned below is a note George H. W. Bush sent me eight weeks before his son, egged on by the same “crazies” his father knew well from earlier incarnations, launched an illegal and unnecessary war for regime change in Iraq — unleashing chaos in the Middle East.

Shut Out of the Media

By January 2003, it was clear that Bush-43 was about to launch a war of aggression — the crime defined by the post-WWII Nuremberg Tribunal as “the supreme international crime differing from other war crimes only in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole.” (Think torture, for example.) During most of 2002, several of us former intelligence analysts had been comparing notes, giving one another sanity checks, writing op-eds pointing to the flimsiness of the “intelligence” cobbled together to allege a weapons-of-mass-destruction “threat” from Iraq, and warning of the catastrophe that war on Iraq would bring.

Read more on John Bolton

- Here’s How John Bolton Could Sabotage the Korea Peace Talks

- Bolton’s Regime-Change Mentality Includes Latin America Among His Targets

- Bolton’s Past Advocacy for Israel at US Expense Heralds Dangerous New Era in Geopolitics

- Regime Change, Partition, and “Sunnistan”: John Bolton’s Vision for a New Middle East

Except for an occasional op-ed wedged into the Christian Science Monitor or the Miami Herald, for example, we were ostracized from “mainstream media.” The New York Times and Washington Post were on a feeding frenzy from the government trough and TV pundits were getting high ratings by beating the drum for war. Small wonder the entire media was allergic to what we were saying, despite our many years of experience in intelligence analysis. Warnings to slow down and think were the last thing wanted by those already profiteering from a war on the near horizon.

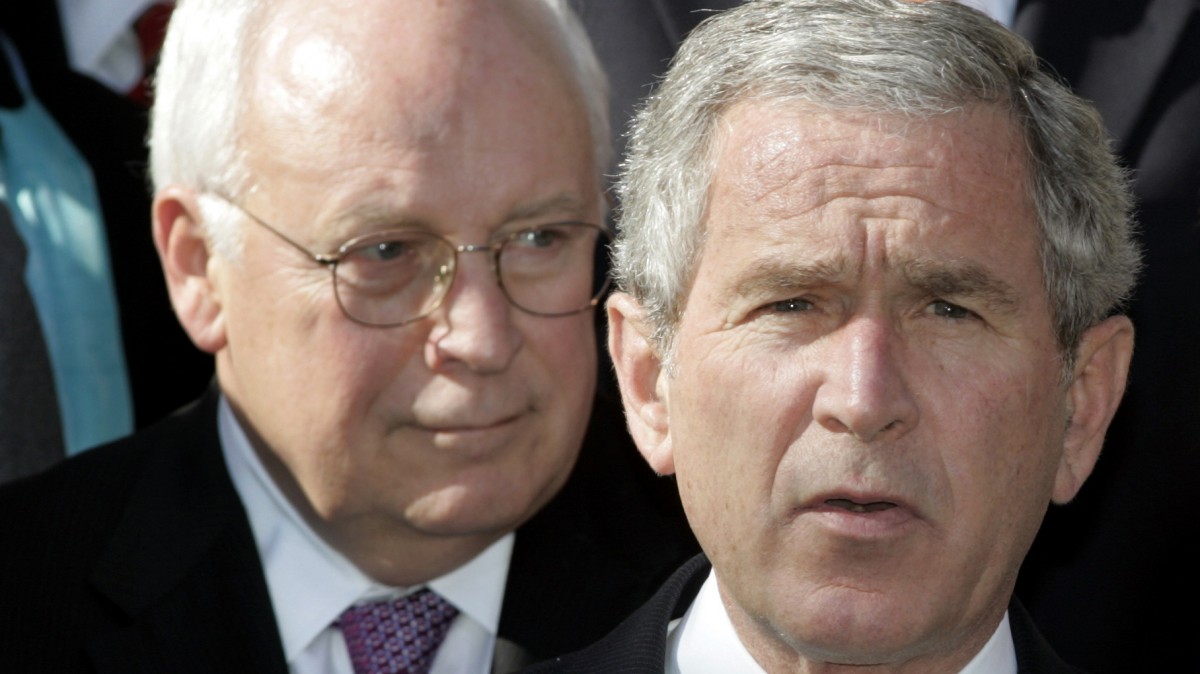

The challenge we faced was how to get through to President George W. Bush. It had become crystal clear that the only way to do that would be to do an end run around “the crazies” — the criminally insane advisers that his father knew so well — Vice President Dick Cheney, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, and Undersecretary of State John Bolton.

Bolton: One of the Crazies

John Bolton was Cheney’s “crazy” at the State Department. Secretary Colin Powell was pretty much window dressing. He could be counted on not to complain loudly — much less quit — even if he strongly suspected he was being had. Powell had gotten to where he was by saluting sharply and doing what superiors told him to do. As secretary of state, Powell was not crazy — just craven. He enjoyed more credibility than the rest of the gang and rather than risk being ostracized like the rest of us, he sacrificed that credibility on the altar of the “supreme international crime.”

In those days Bolton did not hesitate to run circles around — and bully

— the secretary of state and many others. This must be considered a harbinger of things to come, starting on Monday, when the bully comes to the china shop in the West Wing. While longevity in office is not the

hallmark of the Trump administration, even if Bolton’s tenure turns out to be short-lived, the crucial months immediately ahead will provide Bolton with ample opportunity to wreak the kind of havoc that “the crazies” continue to see as enhancing U.S. — and not incidentally — Israeli influence in the Middle East. Bear in mind, Bolton still says the attack on Iraq was a good idea. And he is out to scuttle the landmark agreement that succeeded in preventing Iran from developing a nuclear weapon any time soon.

Trying to Head Off War

In August 2002, as the Bush-43 administration and U.S. media prepared the country for war on Iraq, the elder Bush’s national security advisor, Gen. Brent Scowcroft, and Secretary of State James Baker each wrote op-eds in an attempt to wean the younger Bush off the “crazies’” milk. Scowcroft’s Wall Street Journal op-ed of August 15 was as blunt as its title, “Don’t Attack Saddam.” The cautionary thrust of Baker’s piece in the New York Times ten days later, was more diplomatic but equally clear.

But these interventions, widely thought to have been approved by Bush-41, had a predictable opposite effect on the younger Bush, determined as he was to become the “first war president of the 21st Century” (his words). It is a safe bet also that Cheney and other “crazies” baited him with, “Are you going to let Daddy, who doesn’t respect ANY of us, tell you what to do?”

All attempts to insert a rod into the wheels of the juggernaut heading downhill toward war were looking hopeless, when a new idea occurred. Maybe George H. W. Bush could get through to his son. What’s to lose? On January 11, 2003 I wrote a letter to the elder Bush asking him to speak “privately to your son George about the crazies advising him on Iraq,” adding “I am aghast at the cavalier way in which the [Richard] Perles of the Pentagon are promoting the use of nuclear weapons as an acceptable option against Iraq.”

Read more by Ray McGovern

- NBC Gives a Boost to Vladimir Putin’s Presidential Campaign

- My First Day as CIA Director

- The FBI’s Heavy Hand in the Russia-Gate Scandal

- Seymour Hersh Joins Ranks Of Truth-Tellers Honored For Integrity

My letter continued: “That such people have the President’s ear is downright scary. I think he needs to know why you exercised such care to keep such folks at arms length. (And, as you may know, they are exerting unrelenting pressure on CIA analysts to come up with the “right” answers. You know how that goes!)”

In the letter I enclosed a handful of op-eds that I had managed to get past 2nd-tier mainstream media censors. In those writings, I was much more pointed in my criticism of the Bush/Cheney administration’s approach to Iraq than Scowcroft and Baker had been in August 2002.

Initially, I was encouraged at the way the elder Bush began his January 22, 2003 note to me: “It is only ‘meet and right’ that you speak out.” As I read on, however, I asked myself how he could let the wish be father to the thought, so to speak. (Incidentally, “POTUS” in his note is the acronym for “President of the United States;” number 43, of course, was George Jr.)

The elder Bush may not have been fully conscious of it, but he was whistling in the dark, having long since decided to leave to surrogates like Scowcroft and Baker the task of highlighting publicly the criminal folly of attacking Iraq. The father may have tried privately; who knows. It was, in my view, a tragedy that he did not speak out publicly. He would have been very well aware that this was the only thing that would have had a chance of stopping his son from committing what the Nuremberg Tribunal defined as “the supreme international crime.”

It is, of couse, difficult for a father to admit that his son fell under the influence — this time not alcohol or drugs, but rather the at least equally noxious demonic influence of “the crazies,” which Billy Graham himself might have found beyond his power to exorcise. Maybe it is partly because I know the elder Bush personally, but it does strike me that, since we are all human, some degree of empathy might be in order. I simply cannot imagine what it must be like to be a former President with a son, also a former President, undeniably responsible for such widespread killing, injury and abject misery

Speaking Out — Too Late

It was a dozen years too late, but George H.W. Bush finally did give voice to his doubts about the wisdom of rushing into the Iraq War. In Jon Meacham’s biography, “Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush,” the elder Bush puts most of the blame for Iraq on his son’s “iron-ass” advisers, Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, while at the same time admitting where the buck stops. With that Watergate-style “modified, limited hangout,” and his (richly deserved) criticism of his two old nemeses, Bush-41 may be able to live more comfortably with himself, hoping to get beyond what I believe must be his lingering regret at not going public when that might have stopped “arrogant” Rumsfeld and “hardline” Cheney from inflicting their madness on the Middle East. No doubt he is painfully aware that he was one of the very few people who might have been able to stop the chaos and carnage, had he spoken out publicly.

Bush-41’s not-to-worry note to me had the opposite effect with those of us CIA alumni alarmed at the gathering storm and the unconscionable role being played by those of our former CIA colleagues still there in manufacturing pre-Iraq-war “intelligence.” We could see what was going on in real time; we did not have to wait five years for the bipartisan conclusions of a five-year Senate Intelligence Committee investigation. Introducing its findings, Chairman Jay Rockefeller said: “In making the case for war, the Administration repeatedly presented intelligence as fact when in reality it was unsubstantiated, contradicted, or even non-existent.”

Back to January 2003: a few days after I received President Bush’s not-to-worry note of January 22, 2003, a handful of us former senior CIA officials went forward with plans to create Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity (VIPS). We had been giving one another sanity checks before finalizing draft articles about the scarcely believable things we were observing — including unmistakable signs that our profession of intelligence analysis was being prostituted. On the afternoon of February 5, 2003, after Powell misled the UN Security Council, we issued our first (of three) VIPS Memoranda for the President before the war. We graded Powell “C” for content, and warned President George W. Bush, in effect, to beware “the crazies,” closing with these words:

“After watching Secretary Powell today, we are convinced that you would be well served if you widened the discussion … beyond the circle of those advisers clearly bent on a war for which we see no compelling reason and from which we believe the unintended consequences are likely to be catastrophic.”

Team B

When Gerald Ford assumed the presidency in August 1974, the White House was a center of intrigue. Serving as Chief of Staff for President Ford, Donald Rumsfeld (1974-75), with help from Dick Cheney (1975-76), engineered Bush’s nomination to become CIA Director. This was widely seen as a cynical move to take Bush out of contention for the Republican ticket in 1976 and possibly beyond, since the post of CIA director was regarded as a dead-end job and, ideally, would keep you out of politics. (Alas, this did not turn out the way Rumsfeld expected — damn those “unknown unknowns.”)

If, at the same time, Rumsfeld and Cheney could brand GHW Bush soft on communism and brighten the future for the Military-Industrial Complex, that would put icing on the cake. Rumsfeld had been making evidence-impoverished speeches at the time, arguing that the Soviets were ignoring the AMB Treaty and other arms control arrangements and were secretly building up to attack the United States. He and the equally relentless Paul Wolfowitz were doing all they could to create a much more alarming picture of the Soviet Union, its intentions, and its views about fighting and winning a nuclear war. Sound familiar?

Bush arrived at CIA after U.S.-Soviet detente had begun to flourish. The cornerstone Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty was almost four years old and had introduced the somewhat mad but stabilizing reality of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). Crazies and neocons alike lived in desperate fear of losing their favorite enemy, the USSR. Sound familiar?

Bush was CIA Director for the year January 1976 to January 1977, during which I worked directly for him. At the time, I was Acting National Intelligence Officer for Western Europe where post-WWII certainties were unravelling and it was my job to get intelligence community-wide assessments to the White House — often on fast breaking events. We almost wore out what was then the latest technology — the “LDX” (for Long Distance Xerography) machine — sending an unprecedentedly high number of “Alert Memoranda” from CIA Headquarters to the White House. (“LDX,” of course, is now fax; there was no Internet.)

As ANIO, I also chaired National Intelligence Estimates on Italy and Spain. As far as I could observe from that senior post, Director Bush honored his incoming pledge not to put any political gloss on the judgments of intelligence analysts.

Rumsfeld and Wolfowitz, of course, had made no such pledge. They persuaded President Ford to set up a “Team B” analysis, contending that CIA and intelligence community analyses and estimates were naively rosy. Bush’s predecessor as CIA director, William Colby, had turned the proposal down flat, but he had no political ambitions. I suspect Bush, though, saw a Rumsfeld trap to color him soft on the USSR. In any case, against the advice of virtually all intelligence professionals, Bush succumbed to the political pressure and acquiesced in the establishment of a Team B to do alternative analyses. No one was surprised that these painted a much more threatening and inaccurate picture of Soviet strategic intentions.

Paul Warnke, a senior official of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency at the time of Team B, put it this way:

“Whatever might be said for evaluation of strategic capabilities by a group of outside experts, the impracticality of achieving useful results by ‘independent’ analysis of strategic objectives should have been self-evident. Moreover, the futility of the Team B enterprise was assured by the selection of the panel’s members. Rather than including a diversity of views … the Strategic Objectives Panel was composed entirely of individuals who made careers of viewing the Soviet menace with alarm.”

The fact that Team B’s conclusions were widely regarded as inaccurate did not deter Rumsfeld. He went about promoting them as valid and succeeded in undermining arms control efforts for the next several years. Two days before Jimmy Carter’s inauguration Rumsfeld fired his parting shot, saying, “No doubt exists about the capabilities of the Soviet armed forces” and that those capabilities “indicate a tendency toward war fighting … rather than the more modish Western models of deterrence through mutual vulnerability.”

GHW Bush in the White House

When George H. W. Bush came into town as vice president, he got President Reagan’s permission to be briefed with “The President’s Daily Brief” and I became a daily briefer from 1981 to 1985. That job was purely substantive. Even so, my colleagues and I have been very careful to regard those conversations as sacrosanct, for obvious reasons. By the time he became president in 1989, he had come to know, all too well, “the crazies” and what they were capable of. Bush’s main political nemesis, Donald Rumsfeld, could be kept at bay, and other “crazies” kept out of the most senior posts — until Bush the younger put them in positions in which they could do serious damage. John Bolton had been enfant terrible on arms control, persuading Bush-43 to ditch the ABM Treaty. On Monday, he can be expected to arrive at the West Wing with his wrecking ball.

Even Jimmy Carter Speaks Out

Given how difficult Rumsfeld and other hardliners made it for President Carter to work with the Russians on arms control, and the fact that Bolton

has been playing that role more recently, Jimmy Carter’s comments on Bolton — while unusually sharp — do not come as a complete surprise. Besides, experience has certainly shown how foolish it can be to dismiss out of hand what former presidents say about their successors’ appointments to key national security positions. This goes in spades in the case of John Bolton.

Just three days after Bolton’s appointment, the normally soft-spoken Jimmy Carter became plain-spoken/outspoken Jimmy Carter, telling USA Today that the selection of Bolton “is a disaster for our country.” When asked what advice he would give Trump on North Korea, for example, Carter said his “first advice” would be to fire Bolton.

In sum, if you asked Bush-41, Carter’s successor as president, how he would describe John Bolton, I am confident he would lump Bolton together with those he called “the crazies” back in the day, referring to headstrong ideologues adept at blowing things up — things like arms agreements negotiated with painstaking care, giving appropriate consideration to the strategic views of adversaries and friends alike. Sadly, “crazy” seems to have become the new normal in Washington, with warmongers and regime-changers like Bolton in charge, people who have not served a day in uniform and have no direct experience of war other than starting them.

Top Photo | President Donald Trump’s pick for national security adviser John Bolton, left, walks up the steps with Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, as Bolton arrives at the Pentagon, Thursday, March 29, 2018, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

Ray McGovern works with Tell the Word, a publishing arm of the ecumenical Church of the Saviour in inner-city Washington. He served as an Army Infantry/Intelligence officer and then as a CIA analyst for a total of 30 years. In January 2003, he co-founded Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity (VIPS) and still serves on its Steering Group.