ATHENS, GREECE and LAS PIEDRAS, PUERTO RICO – Until recently, the similarities were stunning. Puerto Rico, mired in a deep economic crisis for the past decade, has often been dubbed “The Greece of the Caribbean.” While there are a great many similarities in the “debt crises” both Greece and Puerto Rico have been experiencing, this superficial description hid a deeper truth: that colonial Puerto Rico, under the control of Washington and a Washington-imposed “fiscal control board” or “junta,” strongly resembles neocolonial Greece, under the thumb of the “troika” (the European Union, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund), on many levels above and beyond the economic difficulties both nations are experiencing.

This all changed after Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico. While the hurricane itself left a trail of destruction all across the island, the real catastrophe is the perfect storm of colonialism, bureaucracy, cronyism, and disaster capitalism that has followed. Almost two months after the hurricane, much of Puerto Rico remains without access to electricity, water, or telephone and internet service.

As the humanitarian crisis on the island continues to deepen, Puerto Rico’s colonial governing regime, and its U.S.-imposed “fiscal review board,” could be accused of sabotaging recovery efforts on behalf of monied interests.

Déborah Berman-Santana is a retired professor of geography and ethnic studies at Mills College in Oakland, California. Now permanently residing in Puerto Rico, she was fortunate enough to be in Greece when Hurricane Maria struck the island. Part One of the interview with Berman-Santana that follows was recorded in Athens in early September and broadcast on Dialogos Radio:

It largely focuses on the colonial similarities between Puerto Rico and the nominally independent country of Greece. Part Two of this interview occurred with Berman-Santana safely back in Puerto Rico, describing the destruction Hurricane Maria left behind and how recovery efforts are actively being stymied by colonial and U.S. authorities.

MPN: Puerto Rico has been facing a severe economic assault across multiple fronts. Just as Greece has the so-called troika, Puerto Rico has the so-called junta, which of course is also a historically loaded word in Greece. Describe the austerity measures and cuts and reforms that the junta has been imposing, or attempting to impose, in Puerto Rico.

DBS: The United States Congress imposed a fiscal control board, which in Spanish is “junta de control fiscal.” It has been in place for a year. Basically, when they do not approve of something in the Puerto Rican government’s budget, they say no, this is not acceptable, you need to cut this, this, this, and this.

They do not necessarily have information on how best to operate — for example with the university, the public university of Puerto Rico, they want massive cuts. They do not even have information on the university, they have not asked for information to see if there must be cuts, where might be the best place to cut. It’s just basically taking a machete and chopping it up. However, they have also increased the budget for themselves.

The U.S. Congress bill, the PROMESA bill that we talked about last year, directed Puerto Rico to pay $2 million per month for the expense of the junta. The new budget the junta inserted said that they must be paid $5 million per month! And of course they use this for all their expenses; they use this to hire dozens of contractors for publicity, for legal fees, for lobbying, for who knows what. These are all their friends.

They have also created a new entity, which is basically in charge of seeing how we can privatize and sell off public resources. I believe that [German finance minister] Schauble, last year or two years ago, created some fund in Greece, basically the privatization fund. Well, this is basically what they inserted into our budget just now. And of course, they’re saying that the pensions must be slashed and there must be more furloughs of public workers.

The government of Puerto Rico is going through a theater; they’re saying “oh, we’re not going to cut.” We all know that the government of Puerto Rico is not going to really fight this. This is just a theater so that their supporters think that it is fighting the junta.

MPN: A big issue during the hurricane, of course, is the proposed privatization of Puerto Rico’s energy utility. How have the junta and proponents of privatization attempted to use the hurricane and its aftermath to make a case for the privatization of the electric company?

DBS: Interestingly, the case was actually made before [Hurricane Irma], for years now. Also, the government lackeys who are the managers of the [energy] authority — not the actual workers of course — have been cutting and cutting and cutting and not re-hiring and re-training enough people to work, and trying to get contractors to work for less money. And so, the infrastructure has been deteriorating — and of course, when people get upset, they say that it’s because it’s public and if it were privatized if we had more competition, it would work out better.

The interesting thing is that the only reason we are recovering much more quickly [from Hurricane Irma] is that [the privatization argument] is a complete lie. For example, before the hurricane hit, the government head of the [energy] authority said that it can take five to six months before we can put [the grid] together because the electric energy authority is so bad.

Well, here we are a week later, almost all of Puerto Rico is back online. San Juan is, interestingly, not completely, although the mountain towns are, and the union of workers are claiming that they are being deliberately impeded from finishing in San Juan, so that people will still be angry and demand privatization.

This is the most militant union in Puerto Rico, and they’re wonderful. They are really our best union that’s left, and they’re of course “left.” They’re working 16-hour shifts — unbelievable photos if you saw them — and they are working, doing heroic things to get Puerto Rico back online. So the interesting thing is, Irma has actually not been good for the arguments for privatization.

MPN: Just as in Greece, Puerto Rico is being sold the promise of foreign investment and large-scale, critical infrastructure projects that supposedly are meant to foster economic growth and development and recovery on the island. What sorts of projects are being proposed and what would their actual impact likely be?

DBS: Part of the PROMESA bill is for “critical infrastructure energy projects,” not for the distribution infrastructure but for [combustible] energy — gas or coal. That’s not what we actually need. If they actually wanted to do something, maintenance, and reconstruction of the transmission infrastructure, that might be helpful — but that’s not where the money is, that’s not where the profits are.

The critical-infrastructure energy projects basically say “we want to streamline the permitting process.” There are many processes — of course, we are a colony of the United States, so we have their laws and ours; and the process of permits takes years for any massive project because there are the environmental issues, there are land use issues, there are public hearings you have to do. They want to streamline it to, I think, 90 days — which means that we have a project and we don’t want to tell the public, we want to get it done as quickly as possible. Also because they want to avoid protests.

For example, the popular protests have stopped two projects for gas ducts. This is over the past years, not just now. These would be gas lines that they would start from natural gas [fields] in the south and they would blast through the mountains — remember that Puerto Rico is very mountainous — and go to the northern side where San Juan is. We have had civil disobedience; we have had legal teams basically challenge these in the courts; we’ve prepared testimony for all the public hearings. Well, they want to bring [the pipeline proposals] back, but without the public hearings, and the local government has passed laws to criminalize civil disobedience.

So this is how they intend to do this: they have an energy-generating project, burning garbage to create energy, and we don’t even have enough garbage! And they don’t say this, but what the project really is, is to burn the garbage [from] all around the Caribbean. But of course, it doesn’t matter what happens to us because they’d like us to emigrate anyway.

We have managed to stop it, but they have just contracted a coordinator of the critical energy projects. He is a Puerto Rican-born — I’m not going to say he’s Puerto Rican — U.S. military man whom they’re going to put in charge of putting this together. I have seen him interviewed several times. He knows nothing! He is completely ignorant — he is just there to facilitate this [project], the gas ducts.

I am sure they have other things that they are planning, things that they have tried to do before that they could not do because of protests. If they get rid of the protesters, then they can just shove it all through. Of course, gas projects, coal projects, maybe mining. We have copper, we stopped the copper mining plans 20 to 30 years ago. Maybe that’s coming back again.

MPN: Recent big news in Greece is the sudden departure of Canadian mining firm Eldorado Gold from the Skouries gold mine in northern Greece (since postponed), which has been a hotbed of activist activity in recent years, owing to its environmental impact and dubious economic benefits, despite its being described as the biggest foreign investment in Greece. We are seeing something similar in Puerto Rico, with the controversy over a privately-owned coal-powered plant and the dumping of the coal ash from this plant. Tell us about this issue.

DBS: Even though our electric energy authority is public, we do have a few private plants, and of course some of the energy-generating implements are private. For example, we do have a couple of projects of windmills from Siemens. They’re looking at Puerto Rico, I guess, as Greece in the Caribbean.

In the 1990s, Applied Energy Systems (AES), which is a multinational corporation based in the United States, proposed a “clean coal” plant in Puerto Rico that was supposed to give more energy generation capacity for Puerto Rico. And of course there’s a myth that Puerto Rico does not have enough energy-generating capacity, and that is [supposedly] why our energy bills are so high. So that was their argument.

I actually participated in the campaign to stop it from getting built. So what they did — this was on the south coast — was to bring the local community to one of their clean-looking plants in the United States, and they took them out and basically told them we’ll give you many jobs and it’s very clean and you shouldn’t listen to these “radicals,” like me, who don’t even live in your community, since they’re against everything.

So they finally did get the permits to build, because they promised that they would not dump the coal ash in Puerto Rico. They finally built it — starting in 2004 — and they were dumping the coal ash in the Dominican Republic. What happened in the Dominican Republic, people started getting sick and launched a campaign against AES. There was a trial, they had a settlement, and part of the settlement is that they would stop dumping in the Dominican Republic. In the Dominican Republic, they have other types of plants; they don’t have coal plants. But they still had the contract [which said] they could not dump in Puerto Rico. So there were some illegal dumps.

Finally, they also had another idea — that they would take some of the ash, you put water on it and it becomes something called “agrimax,” and you can use that as a building material, and they built roads in Puerto Rico, they built homes in Puerto Rico. This is the asbestos of the 21st century. [Agrimax has been used] in many, many communities, mainly in the south of Puerto Rico, and San Juan is in the north. In San Juan [the prevailing attitude] is, what happens in the provinces stays in the provinces.

So in 2014, the government of Puerto Rico did a secret amendment to the contract, which allowed AES to dump the ashes in two of the landfills in Puerto Rico. One of them is actually not far from where I live, and the other one is in Peñuelas [in the south], in an area where we had the old petrochemical complexes, still dealing with a legacy of pollution.

So they filled up the one near where I live and they couldn’t dump there anymore for a while. They started dumping in 2015 in the one in Peñuelas, but that community has been dealing with the legacy of contamination for many years, and they started the protest camps, they started doing civil disobedience. It became an issue. With this government, the government agreed because there was a lot of pressure, and we’ve had a lot of arrests, a lot of civil disobedience.

[Recently] there was a trial, in San Juan, of the last group of people arrested there. At this point, the government of Puerto Rico had said we’re going to pass a law that prohibits the dumping of the ash, but they inserted a little amendment at the last minute, written by the company, that said that the ash is only what’s dry. If you put water on it, it becomes Agrimax. And so, they started again with the dumping. They’ve had to dump at night with four hundred police [officers] to protect them, and there are still people protesting, so this is a big deal.

Of course, they couldn’t do anything during [Hurricane Irma]. We found out that they did not even bother to cover the mountain of ash that they have next to the plant. Who knows where this ash is right now. It’s everywhere! And so the struggle continues. That is the story, and they’ve also said “Oh, you need our generating capacity,” because they have a plant. But they only generate maybe 11 percent of what we need.

They close every time there’s a problem. The public plants never close. We don’t even need their plant because Puerto Rico has twice the generating capacity that it needs, and if we maintained everything we would never need them. In fact, we don’t need them now.

MPN: In yet another similarity with contemporary Greece — where there is an activist movement that has sprung up surrounding the case of a student by the name of Irianna, who is facing charges under Greece’s anti-terror laws for participation in a terror group — in Puerto Rico there is the case of political prisoner Nina Droz. Why has she been imprisoned and what in your view are the similarities with the Irianna case?

DBS: I think the main similarity has to do with using a test case to see if you can turn the public against such a person — and also to scare people, to make them afraid to protest. Specifically in the case of Nina Droz, [she] was not really involved in any organized critical activism; she’s a student, a model, teaches also. She is a party girl, lots of tattoos, so there could be a lot of prejudice against her because of how she looks.

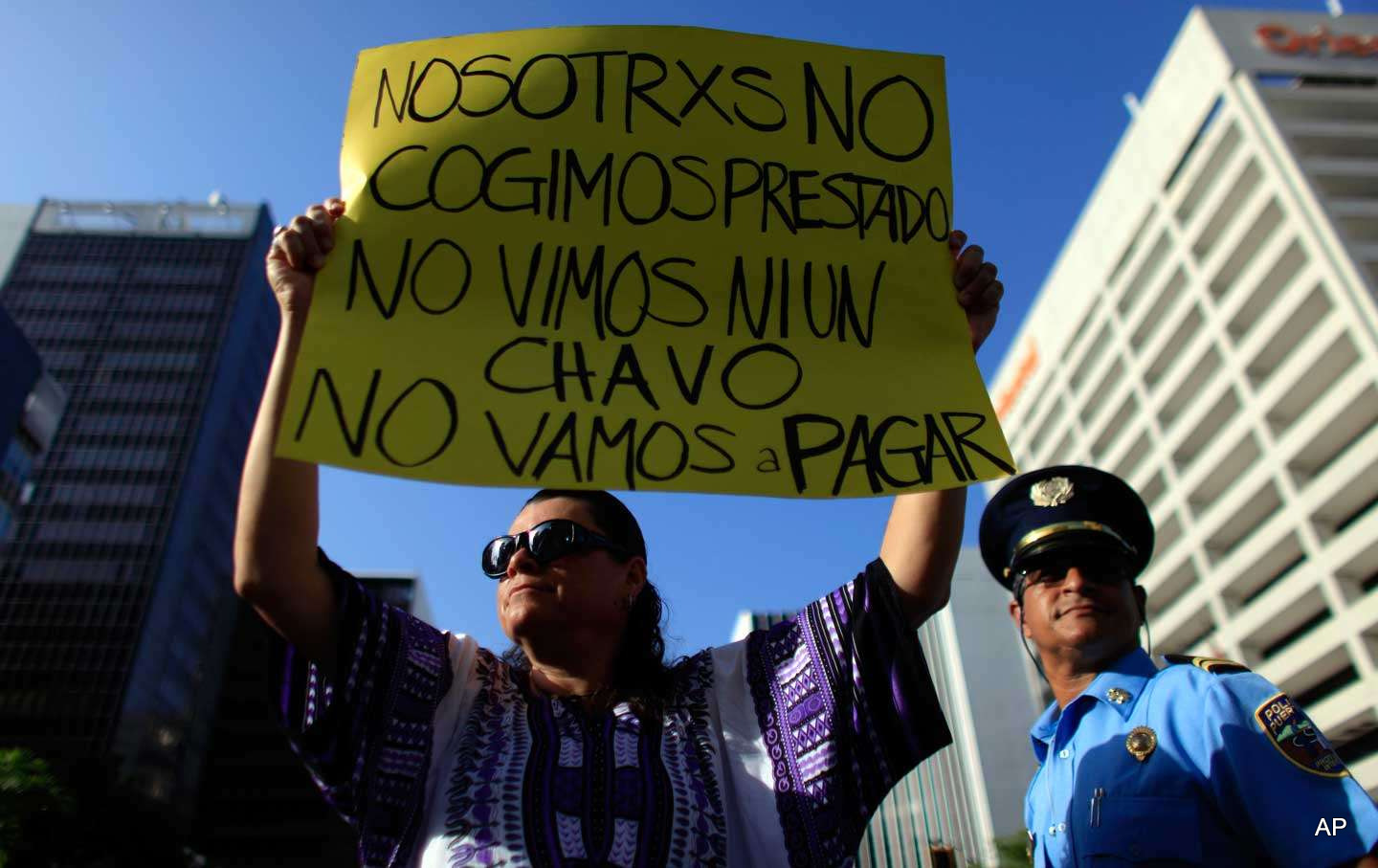

[On] May 1, we had a massive demonstration in Puerto Rico against the junta, against austerity, and, for most of us, against the [colonial status], because some of us know that the real problem is not the junta. The problem is that we’re a colony.

It was a massive protest. On one side there was a group of masked students or masked people — who knows who they were! — all dressed in black. Many of the banks were actually boarded up and protected, except for our most important bank, Banco Popular de Puerto Rico. The nephew of the head of Banco Popular is the president of the junta, to give you an idea. They did not cover up their windows, and there was a moment where all the police withdrew, and there was a group of people in masks who broke the windows. No police around.

According to some of the TV coverage and some photos, there was a young woman who has since been identified as Nina [Droz] who was with an unidentified masked man. They are on the sidewalk next to one of the windows that’s been busted. It looks like perhaps they’re trying to light a piece of paper, and nothing happens.

But one of her feet is inside the bank, and based on that, the U.S. federal government says—there were some other people arrested but they were processed in the Puerto Rican system—they said Nina is in the U.S. system, because she is inside the bank and the bank is involved in interstate commerce and it’s [covered under federal law]. So she has been charged in the media and by the federal court with conspiracy, attempted terrorism, for trying to “blow up” this building with a little piece of paper which may or may not have had some fire on it.

[As of the time of this interview], Nina has not had a trial. She was assigned a federal defense attorney, a public attorney. There is a gag law against her attorney, so they cannot respond to anything in the media, and she’s been demonized in the media. She is in the federal holding court — she originally pled not guilty to all charges. After about two months she agreed to a plea deal to conspiracy, which is very vague, in exchange for reduced time.

(Josian E. Bruno Gómez/EL VOCERO)

But she still [as of the time of this interview] has not been sentenced, and there have been issues such as, for example, her birthday. Some of us were going to [organize] something outside the prison with a sign, “Happy Birthday,” just a little thing, and the prisoners can normally see that. Right before that, there was some “infraction,” who knows what, and they put her in solitary, and she was in solitary for almost a month. She was not given the reasons for it — because there’s a process, everything was delayed — and now they say she cannot even have visitors, not even her mother, if you can imagine that.

The sentencing [was] supposed to be at the end of October, and even the prosecutor has suggested two years [imprisonment]; her attorneys have suggested one year, but the judge could give her more. You never know what can happen. Evidently, she is not as obedient as they’d like, and she has complained about things, and the only reason we know anything about what’s happened is that she can send and receive letters. I myself have received a letter from her. And, there is a friend who is an attorney — not her attorney but able to visit her and able to talk a little bit about the situation, with a lot of care. She’s very careful.

Actually, I’ve talked to [theattorney] before I came here [to Greece] to discuss what she thought I could talk about here in Greece. So when I heard about the Irianna case, it struck me — I know there are differences, but it nevertheless struck me — that the system criminalized her for supposed associations, alleged associations that may or may not be true. And it used these charges to justify a very long sentence for a young woman who basically, if she has to serve a whole sentence, it’s a terrible thing. The same thing with Nina [Droz].

Nina, her letter is wonderful to read; it made me cry when I received it, and she says:

We should never be afraid to speak up for justice, to speak up for what’s right, and to give a voice to those who have no voice, and you can count on me to give my voice until the end of my days.”

So I just wanted to share that. People are writing to her and we want her to know that she’s not alone. This is a little different situation from some of our early political prisoners, who spent many years in organizations and they had a very strong political formation which enabled them to survive many years in prison. Nina doesn’t have that background, but she’s one of us.

MPN: Continuing this theme of parallels between Greece and Puerto Rico, in Greece the current U.S. Ambassador Jeffrey Pyatt was until recently the U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine. In Puerto Rico, an individual by the name of Natalie Jaresko, who herself attained infamy in Ukraine, is now the executive director of the junta in Puerto Rico. What is Jaresko’s background and what is her role now in Puerto Rico?

DBS: Natalie Jaresko was born in Chicago of Ukrainian parents. She has a graduate degree in economics from the University of Chicago, which is infamous for its economics department, widely views as the birthplace of neoliberal economic theory. She has worked in the State Department, she has worked with the IMF [International Monetary Fund], and we think she is a CIA asset. She’s also a fellow at the Aspen Institute, and you can even see pictures of her with “Open Ukraine” behind her — and that may ring some bells to some people, anything that’s “Open Society.”

She is definitely accused of enriching her own company in Ukraine from the privatization and sale of the telecommunications network there. She was only there for a couple of years. They gave her Ukrainian citizenship, I think, within one day. She was named to be the finance minister right after the coup, so she was basically put in as Ukraine’s finance minister by the United States, and the little minor detail that she wasn’t a Ukrainian citizen [was overlooked], so they gave her Ukrainian citizenship.

Natalie Jaresko, she still goes back and forth to Ukraine, and part of her contract with Puerto Rico is we pay for business-class trips once a month from Puerto Rico to Ukraine. She was named by the junta to be the executive director. She is of Ukrainian background so she at least speaks Ukrainian, but she knows nothing about Puerto Rico — zero. She is there to do the same thing or worse in Puerto Rico as she did in Ukraine.

When I write about her, I always say Natalie “Carnicera de Ukrania” Jaresko — that’s Natalie “Butcher of the Ukraine” Jaresko. I just have to give you some of the terms of her contract. Her annual salary, which we are paying for, [is] $625,000 a year. That is more than $200,000 more than the president of the United States earns. And she has all of her expenses [paid for]; she has a private suite in a luxury hotel; she has an entire security detail and all of her communications, and she has her nice business trips to the Ukraine and anywhere else she wants to go.

In exchange for that, she comes in and says well, you need to cut and slash — for example, the university budget: the University of Puerto Rico needs to be more like the United States’ public universities. In other words, we should slash the government’s share of the budget to the university and students should all go into debt and become debt slaves, like they are in the United States. It’s [currently] relatively inexpensive.

The University of Puerto Rico is an excellent, excellent university. It is the best university system [on Puerto Rico], with 11 campuses (of course, they want to slash, cut all the campuses, maybe two or three left). Much better than the private universities, and it is the vehicle for people — the best students in Puerto Rico, especially if they’re poor — to get an education and to contribute to the future of Puerto Rico. They’re an incredible resource, and it is also a very militant university.

The students have had many strikes. They had one a few months ago — they shut it down for two months, and the issue was the cuts. It was interesting, they actually had a personal meeting with the junta, face-to-face, that lasted all day, which is something that the government of Puerto Rico has not even had. The students managed to do that and actually had a list of demands, none of which have been fulfilled, but just to give you an idea.

Natalie Jaresko has also said that I am here to help Puerto Rico, you need to listen to me, I’m going to cut everything. By the way, the government of Puerto Rico said we are not going to hurt the most vulnerable. Of course, they never identify who are the most vulnerable. The PROMESA bill says “essential services” must be protected. Of course, they are never defined, what “essential services” are.

They also have hired a special security detail and they are lobbying to expand the new criminalization law to further criminalize protests against the junta. So this should give you an idea of what the “Butcher of the Ukraine” wants to do in Puerto Rico.

MPN: Let’s turn now to the hot-button issue of Puerto Rico’s political status. A few months ago we saw a nonbinding referendum on statehood take place — an issue that, from what I understand, remains extremely divisive in Puerto Rico and parallels the debate that we see in Greece regarding continued membership in the European Union. Describe for us the current state of affairs regarding the island’s political status and the political divisions in Puerto Rico.

DBS: As I have noted in speaking with you before and have published before, Puerto Rico is a colony, is an “unincorporated territory belonging to but not part of the United States.” That is its official designation according to the U.S. Supreme Court. We do not even have the limited sovereignty of a Native American tribe, just to give you an example. In the United Nations, we’ve been trying for many years to get the issue [of Puerto Rico’s colonial status] on the agenda of the General Assembly, but have not managed to do so.

It has been extremely divisive because the advocacy of independence has been demonized and criminalized for many, many years in Puerto Rico. There have been many, many imprisonments; there have been many deaths; there have been many disappearances, many people who were unable to find work. And so, many people, most people in Puerto Rico are either very afraid of [independence], or they believe we have no chance, we need to depend on the United States. Most Puerto Ricans are not quite knowledgeable about our own history.

At the present time, one of the major parties is a party that says our current status is okay if we can increase our autonomy. The other major party, which is currently in power, says no, we need equality, we need to become a state, the 51st state of the United States. And then there’s a smaller party and many people who do not vote at all, who say that without independence we cannot even begin to have this conversation because we don’t have control over our own affairs.

Puerto Rico has had five referendums since the 1960s about our political status. None of them was binding. The U.S. Congress has never committed to respecting the results. The last one was in June, and I actually wrote an article that was published in Greece in March, highlighting the interesting thing about that particular proposal, that there would be only two options: one was statehood, and the other was some kind of sovereignty.

Now, that’s kind of a loaded term, not always understood, but many independence supporters thought that this might be an opportunity, if we can actually have a very good showing of people who reject statehood and want some kind of sovereignty, then we might be able to push something. So many people who don’t even ordinarily vote were going to register.

Well, at that point the attorney general of the United States, Jeff Sessions, said to the governor of Puerto Rico that in order to have this referendum, you also need to include the current status. Now this is a referendum for the decolonization of Puerto Rico, that’s the name of it, and he said one of the options has to be to remain a colony. So one of your options to “decolonize” is to stay the way you are. The government said okay! And with that, all of the pro-independence, pro-sovereignty people said forget it, we’re boycotting. Then the other major party, the one that wants the current status with autonomy, also boycotted.

You had, in June, only one party [that] was represented, the pro-statehood party. No more than 23 percent of the voters even voted — and, because there was no oversight by the other parties, it may have been even less than 23 percent. Ninety-seven percent of voters voted in favor of statehood.

With that, the government went to Congress and said “97 percent of the voters want statehood.” They were completely ignored! Then they chose seven people and said “here are our Congressmen and we’re sending them anyway,” and they’re completely ignored, but they’re spending Puerto Rican public money that we supposedly don’t have, and they’re all sitting in Washington.

I’m not sure what they’re doing there, probably eating well and staying at a nice hotel, but Congress is completely ignoring them. They said “we’re going to meet with President Trump.” As far as I know there’s been no meeting. So we have not solved any problem — everything is exactly the way it was, except they spent $10 million of money that we don’t have on the stupid referendum.

MPN: Within this context of the broader economic crisis that Puerto Rico is experiencing, has the independence movement been able to gain any traction?

DBS: That’s always an interesting question. It’s not really easy to answer. One of the problems is that the independence movement, the left in general, is extremely divided. We have many, many little groups. People spend a lot of time, for example, on Facebook attacking each other. It’s very tiring. Sometimes when we have a meeting or protest people do show up together.

The interesting thing is, it’s not easy to say if we have support for independence or more support for independence. What I can say is, maybe there is more understanding that the United States is not going to help us — as if they ever did — that perhaps we need to figure out some way of not waiting for them to “rescue” us or to give us more power or to give us statehood.

The other thing is, because of what’s visibly happening in the United States — it’s always been happening, but the visible attacks, the visible oppression that is now getting a lot of media attention throughout the world — people are starting to believe that well, even if we became a state, we’re still Spanish-speaking, we’re still to a large extent of African descent.

How is it for the Blacks and the Latinos who live in the United States? They have statehood, do they have equality? So it’s beginning to open up things a little more.

The problem that we had is a question of getting rid of our own colonized mentalities, our colonized minds. I think that’s probably our biggest challenge. And to not just speak to ourselves, the people on the left, but to speak to our neighbors, to talk about this, and I constantly am talking to many of my neighbors, none of whom are independence activists, but they always want to ask me what I think about what’s going on.

MPN: One of the biggest stories of the past few months in Puerto Rico is the release of Oscar López Rivera, who was imprisoned in the United States for 34 years and was granted clemency by President Obama in the last days of his administration. Oscar is now back in Puerto Rico. What has the response to his release and repatriation been and what has he been doing since his release?

DBS: Oscar is now physically free — he has been spiritually free for a very long time, freer than many people I know, but he has been physically free, without restrictions, since the 17th of May. There has been a tremendous, overwhelming response among Puerto Ricans to his release, to basically being around. To be around him — I’ve been around a lot of political prisoners, and many of them, it takes a long time to adjust. His adjustment — he may have some adjusting to do that you don’t see, but you meet him in person, the smile, the hugs, he is very, very physical with everyone, for very good reasons.

He is constantly talking about unity, he is talking constantly about the decolonized mind, he is constantly asked to speak. So he has been not only speaking at many activities in Puerto Rico, but also elsewhere, for example in the United States. He wants to thank communities all around the world for supporting him and for campaigning for him, so he’s been in many, many activities

He also went to Nicaragua, was at a conference, and President [Daniel] Ortega gave him the highest recognition of Nicaragua. He is scheduled to visit Cuba in November, and of course they were very, very active in working for his release, as well as release of earlier prisoners. So he is making a lot of the rounds still.

His plan, actually, is trying to set up a foundation to give him a little bit of [financial] independence, so that he can work in Puerto Rico. He was a community organizer before his imprisonment. He wants to do it in Puerto Rico, and he says he specifically wants to work on community-based alternatives, which already exist, but to unify them. He wants to unify the various activists, unify the people of Puerto Rico, speak to the people who are not necessarily activists and to break through this division that we have. He has the stature to force people to at least listen.

I can’t wait — I mean, some of us are a little impatient, we want to do this already, but he’s still speaking on many occasions. Sometimes it’s difficult to contact him — he has some people helping him because he will never say no to anybody, so some of the people who are helping him are trying to shield him a little bit. It’s a little bit of a coming out process, so to speak.

MPN: A famous quote from Oscar López Rivera concerns the struggle for independence and the anti-colonial struggle, which according to Oscar, begins with the decolonization of the mind. How are his words relevant in the present day, both for Puerto Rico and also for Greece, even if the country is nominally independent?

I think part of the problem with the colonized mentality is that the one who is colonized begins to believe the lies that have been told by the colonizer: that we are inferior, we are backward, that we would be poor, that we would have no hope if it were not for a more developed, more civilized, more powerful entity — for example, the United States, and in parallel, Northern Europe and Germany for the European Union. That we need to be developed, we need to be more advanced, we need to be more like them and less like the Global South.

I mean, Puerto Rico is without a doubt part of the Global South. But you get that idea, that we need for them to help us because we cannot help ourselves. We should not depend on ourselves because look how advanced they are, how happy they look, how well off they are, even if it’s not true. And if we believe that, it’s very difficult to do any of this. We won’t believe that we can make decisions on our own. We won’t demand our sovereignty, because we will think that we’re not capable of making those decisions by ourselves.

For many years we were told that if we were independent, Puerto Rico would be like Haiti. That, of course, completely ignores that Haiti, although nominally independent, is under military occupation, which benefits a very small oligarchy and keeps everyone else poor. If Haiti really could take sovereignty for itself, you would see a different Haiti. But that’s what they say to us.

There’s also the issue of our not being a European people — we have some European ancestry from the colonizers, but we are mainly not a European people. We are a Latin American-Caribbean-African-indigenous people with a very long history. We didn’t start our history when Columbus came. We have a history that goes back 7,000 years, and we have a lot of information about it. So we could draw on that and also our own history as Latin American people.

We’re in a lot of isolation. Everyone knows about the blockade the United States has against Cuba, but we have one also [the Jones Act]. It’s different, it’s very difficult for us to have direct contact, direct trade with the rest of the world. We have to do everything through the United States. And so we’re isolated.

I’ve heard many people in Greece say “I don’t know this story, why haven’t I ever heard this story?” I respond that you haven’t heard this story because it’s a blockaded story, it’s blockaded history. It’s one of the reasons that I’m here [in Greece]. And I think that the colonized mind is our biggest obstacle. I have seen that when we work together and we fight against the oppressor, the oppressor cannot stand against that. So that’s our biggest problem — I think it’s a bigger problem than U.S. military might or anything else that they can threaten us with.

MPN: The anti-colonial and independence movements that we’ve seen across the world, including those of the 1960s and 1970s, were by and large nationalist movements. Today though, we see arguments from many who associate nationalism with fascism, with racism, with xenophobia. How do you view the issue? Do you believe nationalism can be compatible with internationalism and a more cooperative worldview?

DBS: This is a very interesting question. I’ve had this conversation with many people. I know that in people there is a specific historical context of nationalism and fascism. I understand that. But the interesting thing, particularly in Latin America, is that the issue of nationalism has to do with national sovereignty, of controlling our own destiny, making our own decisions and not allowing the imperialists or neo-imperialists to make those decisions — whether it’s a European power or whether it’s the United States or whether it’s another country.

So in the context of Latin America, there is a nationalism that is called “anti-imperialist nationalism.” There is a tremendous amount of literature. It is not a nationalism that says we are better than everyone and we want to control others. We want to control ourselves.

Puerto Rico has had a very long history with the Nationalist Party. It’s very small right now, not very active. It was tremendously repressed. Our great martyr, Dr. Albizu Campos, was martyred, really, literally. He was the leader of the Nationalist Party. His politics, his economics, you could say were social democrat, more or less. But one of the main leaders was also Juan Antonio Corretjer, who was a communist. There are some revisionist historians who want to say that he was fascist, [but] there is no evidence for that.

I just want to share something very interesting: only a few months ago I was in Cuba, and we had this conversation because I had my conversations in Greece in mind when we had this conversation [in Cuba]. The people with whom I was talking said:

Of course, you will never find people more nationalist than Cubans. We love our country. We want to keep our culture. We want to defend our country against outside control, but we are internationalists. We want other countries to be able to defend their own sovereignty as well. We want to have relationships of mutual respect.”

And that, for them, is nationalism. And they also said, we understand there is a different history in Europe, but I think we need to rescue this word.

Now I am seeing with the very open racist attacks in the United States, I have heard some European friends say “oh, fascism is coming to the United States.” I say “No, that’s not it exactly. You’re seeing white supremacy, which is the founding principle of the United States, because it’s a European settler-colonizer regime that destroyed many indigenous nations and it maintains power through white supremacy.”

That’s not necessarily the same as fascism, and I believe the word “fascist” is thrown around a lot, but we are not talking about the actual alliance of the state and the private industry and the oligarchy. That seems to be lost a little bit.

So that’s a conversation that I think is very important also in Puerto Rico, because sometimes there are people who have read a lot of literature from Europe and they start saying “I don’t care about independence because it’s nationalist, I care more about socialism,” and I say “okay, but if we’re not independent, how are we going to be socialist? As a colony or as a state of the United States, are you expecting to be socialist? Are you expecting the communist ideal this way?” It’s less likely, I would say, and so I think it’s important to have this conversation in Greece as well.

MPN: This is the third consecutive year that you have visited Greece. What has brought you back to Greece for the third time, and where will you be speaking?

DBS: I’m very happy that I [was] invited back to speak at the Resistance Festival, which [occurred on the] 29th and the 30th of September at the Fine Arts School [in Athens]. I’m very, very happy to be working together with Dromos tis Aristeras, the wonderful weekly which I’ve also been able to send some updates on Puerto Rico and which was very, very active in the campaign to free Oscar.

I have a lifelong interest in and affinity with Greece. I even have some Greek ancestry — this is going way back. but it’s been a lifelong interest, a lifelong appreciation of the popular culture, the music And of course, with the issue of the austerity, with the resistance, and what’s happened with the troika, I immediately saw the similarities with what was happening in Puerto Rico.

And then they started calling Puerto Rico “the Greece of the Caribbean.” It’s a very superficial way that it’s used in the news, but there is a deeper truth there. Sometimes in my writings, I’ve talked about Greece as the “Puerto Rico of the Mediterranean,” because I think that we can learn from each other.

I’m hoping to increase the solidarity, increase learning about each other. At first, it was really just me, I kind of had this idea; now there is starting to be more interest. There are a couple of organizations in Puerto Rico that have contacted me to try to bring some people to speak from Greece, and there is more interest here. There are a number of different organizations [here] that are now trying to make contact with me.

I am open to speaking anywhere, with anyone, in English, in Spanish. I’m learning Greek — I’m still not speaking very well, but I’m reading more and I’m hoping at some point to be able to speak well enough to be able to present. If we have someone come [to Puerto Rico] from Greece who does not know Spanish or English, I hope I’ll know enough to help with that.

But I am hoping that we can continue this collaboration, continue solidarity. Maybe we can have young people from both countries visit each other, cultural exchange with the idea of helping each other’s struggle for a just society, for the ability to take care of ourselves and to stop this continued bleeding of our countries — the continued bleeding of our people, where our young people feel the need to leave.

I don’t want to see a Greece without Greeks. I don’t want to see a Puerto Rico without Puerto Ricans!

Part Two of Michael’s interview with Professor Berman-Santana, conducted in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, will be presented in an upcoming article.