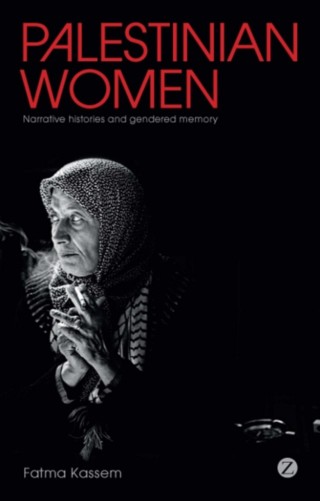

In her book, “Palestinian Women, Narrative Histories and Gendered Memory,” published in 2011 by Zed Books, Dr. Fatma Kassem writes, “Palestinian women living in Israel have been entirely left out of the formation of Palestinian national identity.”

In an effort to bring them in, even if for a moment, she conducted interviews with 20 Palestinian women who had lived through the horrors of 1948. These were women who currently – or at the time of the interviews – lived in Lyd and Ramleh, two Palestinian cities that were occupied in 1948 and subjected to atrocities by the Zionist militias and later to horrifying abuse and discrimination by the government of Israel.

The cities of Lyd and Ramleh, which lay just a few kilometers southeast of the city of Yaffa, were, like Yaffa, full-fledged Palestinian cities prior to 1948, each having a population of close to 20,000. In the summer of 1948, the two cities were subjected to a massive violent campaign of ethnic cleansing. The women interviewed by Dr. Kassem all lived through that horror and now, all these years later, were asked to tell their stories.

The cities of Lyd and Ramleh, which lay just a few kilometers southeast of the city of Yaffa, were, like Yaffa, full-fledged Palestinian cities prior to 1948, each having a population of close to 20,000. In the summer of 1948, the two cities were subjected to a massive violent campaign of ethnic cleansing. The women interviewed by Dr. Kassem all lived through that horror and now, all these years later, were asked to tell their stories.

Admittedly, I have only recently become aware of this book, which is written around the stories of these “ordinary Palestinian women” who represent what Dr. Kassem calls the weakest sector of the population. Some of them were originally from Lyd and Ramleh, some ended up there as internally displaced people. They typically begin their stories with, “I am from here,” or, “I am not from here;” in both cases, the next sentence describes how their world was destroyed and forever transformed when “the Jews entered and took the country.”

Dr. Kassem writes that by telling the stories of these 20 women who survived 1948 she seeks to have those who are responsible “take responsibility for these stories.”

The kitchen and the living room

Dr. Kassem dedicated the first chapter to her own family stories. She writes that long before the new Israeli historians began exposing the atrocities committed by the Zionist brigades in 1948, “I’d already heard the stories many times in our family home.”

Her father, she said, used to tell the stories in the living room: “The living room represents the public space of the home where a much more diverse group of people would visit.” And her mother told her stories in the kitchen, “a private place with a much smaller audience of immediate family members.”

Fleeing for survival

“We fled,” they say one after the other, describing harrowing stories of fleeing violence by the Israeli army. One describes carrying a baby for miles on foot to escape Israeli warplanes.

“In a state of war people leave dangerous and hazardous places in the rational interest of preserving their safety,” Kassem rightfully asserts. However, when people do this they have a right to go back to their homes. Yet the newly formed State of Israel did not permit this. Those who fled are still not permitted to return, and, in fact, Palestinians who tried to return were designated as infiltrators and were arrested or shot on sight.

The women also described in great detail the homes they had lived in prior to 1948. Once Israel had taken over, their homes were either demolished or became the property of Amidar, an Israeli-government-owned housing company.

In 1948, the women’s sense of safety and security was destroyed along with that of their communities and indeed all of Palestine. And yet, against all odds, these women succeeded in the heroic task of remaining in their native homeland, Palestine. They built homes and raised families, albeit in extremely harsh conditions, and they did so in defiance of the Zionists who made claims to their land.

Remembering the bodies

“If you’d only seen the bodies in the streets, if you only had seen the bodies. Little children without their shoes walking about the mayhem and crying.” Several women in the book mention the “death roads” — roads upon which countless Palestinians died following mass expulsions.

They recall seeing the bodies of family members and neighbors, elderly men and women, and even children. They knew these people could not survive the difficult physical conditions, walking for miles and miles in “the heat, hunger and the thirst.”

One of the women recalls, “it was so hot, so hot, they died, they died, bodies were left on the road, there was no drop of water, no water.”

“Some of the women I interviewed,” Kassem says, in what must be a harrowing moment for a mother to hear from another mother, “lost their children on the road of expulsion: ‘We left Isdud. We walked for two hours on foot along the beach. When we left, my daughter was in my arms… There were no doctors and no food.’”

“The silences and facial expressions and the sweat that’s covered her face indicates she was concealing something,” Kassem writes. This mother, understandably, did not want to talk about the death of her two-year-old daughter. In the words of another: “It was the fast, the third day of Ramadan, when this happened and we were fasting. When the Jews came in, they didn’t leave anything to us. Not bread, not water for the children, and the people were expelled into the mountains barefoot and empty-handed, not a drop of water to drink. They threw us out at noon. It was noon so it was so hot.”

Dahmash Mosque

On a personal note, the story of the massacre at the Dahmash Mosque in Lyd was the first story I ever heard of the Zionist atrocities of 1948. I heard about it from someone who had personal knowledge of the massacre. My friend Ibrahim, a Palestinian originally from Lyd, told me how his father was among a group of men whom the Zionists forced to go in and clean up after the massacre.

Several of the women Dr. Kassem interviewed had witnessed this horror. One recounted: “The first days when the Jews came in, people went inside the mosques, they thought that the Jews would not kill them in the mosques. But they killed everyone who was inside.” Another told: “My father and many others went inside the mosque to protect themselves. He was not fighting. He was an old man. My father and my cousin, they pushed them into the mosque and shot all of them.”

Dozens of people seeking refuge in the mosque in Lyd were butchered by the Israeli army. They were buried in a mass grave in the cemetery in Lyd. Today the mosque itself stands as an informal memorial to those who were massacred.

The ghetto

The Cities of Yaffa, Rameh, and Lyd were now occupied by the new state of Israel. The few Palestinians who remained were placed in ghettos. These were streets that the army designated for this purpose, surrounded by barbed wire and heavily guarded by Israeli soldiers.

As one of the women explains, tellingly using the word ghetto to describe conditions at the time, “The Ghetto is where the old city is next to the big mosque.”

Minimal rations of food and water were provided but no one was permitted to leave. Anyone found outside was executed on the spot: “If they wanted to bury a dead person they needed a permit. Otherwise people did not dare to go out.”

“The days are repeating themselves”

The reality of violence against Palestinians is an ongoing story. As they were being interviewed, noticing the reality around them, the women commented: “The days are repeating themselves.” In Gaza, for example, where many of these women’s relatives ended up, people have nothing to eat.

“The more recent suffering of Palestinians,” Kassem writes, “the horrors of dead bodies and of hunger and thirst, link contemporary events to traumatic recollections of these women from 1948.”

At the conclusion of the book, Kassem writes, “the personal life stories of these women acquired additional layers of meaning.” Their very existence raises serious questions about their rights as women, as human beings, as Palestinians, and as citizens of a state that imposed itself upon them and doesn’t want them.

Feature photo | A young Palestinian woman paints a mural to commemorate the one-year anniversary of Israel’s bloody crackdown on Gaza, in Gaza City, Dec. 29, 2009. The Arabic text reads “Gaza,” Hatem Moussa | AP

Miko Peled is an author and human rights activist born in Jerusalem. He is the author of “The General’s Son. Journey of an Israeli in Palestine,” and “Injustice, the Story of the Holy Land Foundation Five.”