Ernesto Che Guevara’s words on guerrilla warfare become particularly resonant on the anniversary of his death on Oct. 9, 1967, when he was murdered at the hands of the CIA and the Bolivian government.

At the time of Che’s murder, U.S. intentions were to stifle the internationalist aspect of the Cuban Revolution – an attempt not only to destroy Che, but also to weaken Fidel Castro. Decades later, Che remains a source of inspiration evoked by many including Fidel, and the Cuban Revolution remains committed to its aims and anti-imperialist ideology.

Che’s dedication to internationalist revolutionary struggle had been evident from the early years of the struggle to bring down the U.S.-backed Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. His inclusion in the revolutionary 26th of July Movement headed by Fidel was based upon an understanding that when the Cuban Revolution was consolidated, Che would earn the freedom to impart revolution wherever his efforts were needed.

The sentiment was expressed in his farewell letter to Fidel, dated April 1, 1965, in which Che formally renounced his leadership positions and Cuban citizenship in order to pursue internationalist revolution elsewhere around the world. “Other nations of the world summon my modest efforts of assistance,” he wrote. “I can do that which is denied you due to your responsibility as the head of Cuba, and the time has come for us to part.”

How the CIA got away with murder

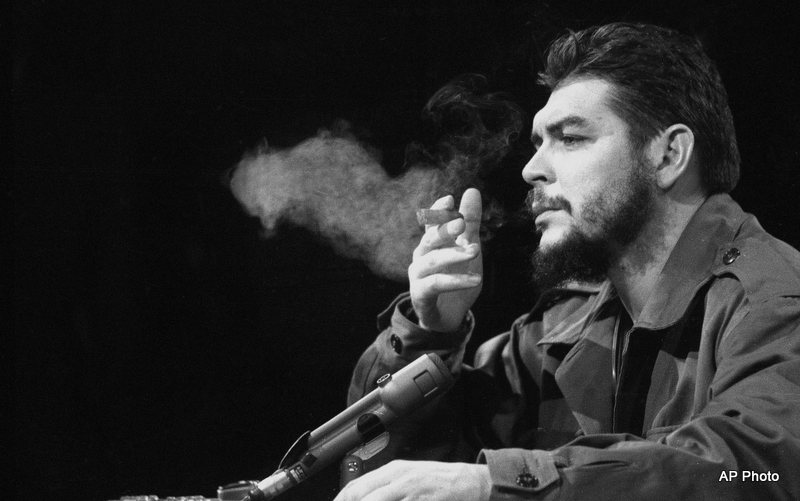

Che’s murder was assigned different narratives for decades. Within a wider framework, the varying narratives regarding the murder — in particular, those upheld by imperialist organs like Western media — were reminiscent of attempts to fragment the Cuban Revolution and its main protagonists, Fidel and Che. The narrative was also distorted by the capitalist exploitation of Cuban photographer Alberto Korda’s iconic image of Che – an image used to portray the downfall of a revolutionary removed from the revolution.

Beyond the usual depiction of Fidel as a “dictator,” further manipulation existed, especially in efforts to separate the origins of the Cuban Revolution from its continuation. Attempting to portray Che’s intellectual role as one eclipsing Fidel’s, this narrative sabotage was used to promulgate a false view that Che’s capture and murder in Bolivia resulted in fragmenting the revolutionary process and internationalist struggle.

Che’s assassination by the CIA, therefore, was held up as an ultimate imperialist triumph, even despite ensuing proof to the contrary. This proof largely includes the steadfastness of the Cuban revolution and its aims, as well as the example set by Che that was embraced by various nations in their own anti-imperialist struggles.

Michael Ratner and Michael Steven Smith, co-authors of “Who Killed Che? How the CIA Got Away With Murder,” shed light upon the paramilitary organization’s targeting of Che, taking into account the legal ramifications as well as historical context.

Biographical accounts of Che’s murder differ, from the complete exoneration of the CIA to vague implications of CIA involvement based on selectively given testimony by CIA officials.

However, declassified documents reproduced in the book clearly portray CIA involvement. As early as 1954, upon his arrival in Guatemala, Che was being tracked by the CIA. In the preface to the book, former President of the Cuban National Assembly Ricardo Alarcon states, “Ernesto Guevara was an object of interest for the American secret services before he entered our history, long before he became Che.”

U.S. concern about Che revolved around the knowledge that internationalism, and therefore, the spread of the Cuban Revolution, was a possibility that necessitated elimination. To defend the revolution, Che deemed it necessary to extend it, especially within Latin America – in direct confrontation with imperialist interests in the region.

According to Fidel in his autobiography “My Life: Fidel Castro with Ignacio Ramonet,” Che was impatient that Bolivia was not yet ready for revolutionary struggle: “I didn’t want him to go to Bolivia to organize a tiny group, I wanted him to wait until a larger force had been organized … Che is a strategic leader; he should go to Bolivia when a sufficiently solid, proven force is ready.”

Fidel’s words proved true, as a few months after Che’s arrival in Bolivia in November 1966 to challenge the CIA-backed presidency of Rene Barrientos, the guerrilla struggle started to disintegrate due to the CIA’s backing of the Bolivian military, infiltration which led to the betrayal of guerrilla positions, as well as a lack of support from Bolivian peasants due to extreme repression.

On Oct. 8, 1967, Che and his group of 17 guerrillas were ambushed by the Bolivian army in a ravine near La Higuera. Wounded in the leg and hampered by a jammed rifle, Che was captured and taken to a little schoolhouse in La Higuera. He was killed the following day by Bolivian Sergeant Mario Terán.

Following a macabre display in which officials posed near Che’s corpse, his hands were cut off and his body buried in a secret location. Not until 1997 was his burial place revealed beneath a landing strip in Vallegrande, Bolivia.

U.S. documents reveal CIA involvement in Che’s murder

Despite attempts to confuse the narrative, declassified CIA documents offer proof of U.S. involvement in Che’s murder. At first glance, the documents read as conflicting testimonies. However, as Ratner and Smith explain in their book, the concept of “plausible deniability” provided ample space for manipulation, as it gave the CIA the freedom to interpret White House discourse without consultation and with complete impunity.

The CIA was created based upon the 1947 National Security Act, which bestowed unlimited powers upon the organization. A further directive in 1948 granted the possibility of various covert operations in violation of international law, thus necessitating the doctrine of plausible deniability in order to allow for complete autonomy without consultation from the president.

In the case of Che, various documents explicitly portray intentions to eliminate him, which can also be viewed as a continuation of the CIA’s plans, albeit unsuccessful, to murder both Fidel and Raul Castro.

A U.S. Department of State Intelligence note titled “Guevara’s Death – The meaning for Latin America” (Oct. 12, 1967) revels in the outcome as a deterrent to other possible revolutions in the region: “’Che’ Guevara’s death was a crippling – perhaps fatal – blow to the Bolivian guerrilla movement and may prove a serious setback for Fidel Castro’s hopes to foment violent revolution in ‘all or almost all’ Latin American countries.”

The perverse triumph should be considered in light of other material evidence that proves that the U.S. government and CIA had knowledge of Che’s activities in Bolivia.

Meanwhile, the responsibility of training the Bolivian military fell upon Felix Rodriguez – a CIA agent who arrived in Bolivia on Aug. 2, 1967. A Cuban-American, Rodriguez was also involved in attempts to assassinate Fidel.

The highest ranking official at the scene when Che was murdered, Rodriguez had attempted to deflect responsibility onto the Bolivians. Yet testimony from Rodriguez himself, which initially led to CIA exoneration, was later changed to indicate that the order to murder Che came directly to him from the CIA. This shows that although the Bolivian Army were willing participants in the struggle to eliminate Che, the army was not in a position to dictate orders to the CIA.

On Oct. 18, 1967, a few days following Fidel’s televised appearance in which Che’s murder was confirmed to the Cuban nation, the revolutionary leader addressed an audience of around 1 million people, delivering a eulogy to Che and reaffirming the continuation of the revolution, as well as the upholding of Che’s example.

“Che has been converted into a model not only for our people, but for all the people of Latin America. Che has reached the highest expression of revolutionary stoicism, the expression of revolutionary sacrifice, the revolutionary struggle,” he said. “There is no other man who has, in these times, ascended to a higher level of international proletarianism.”