MINNEAPOLIS —– When we hear about civil rights movements, we often don’t think of the disabled — but it’s a demographic that has been fighting to live freely in American communities for over 50 years, and their struggle is rarely covered in the media.

They’ve received far less attention than the fight for racial justice for African Americans and equality for LGBT communities, but their cries for equality can be heard today nationwide.

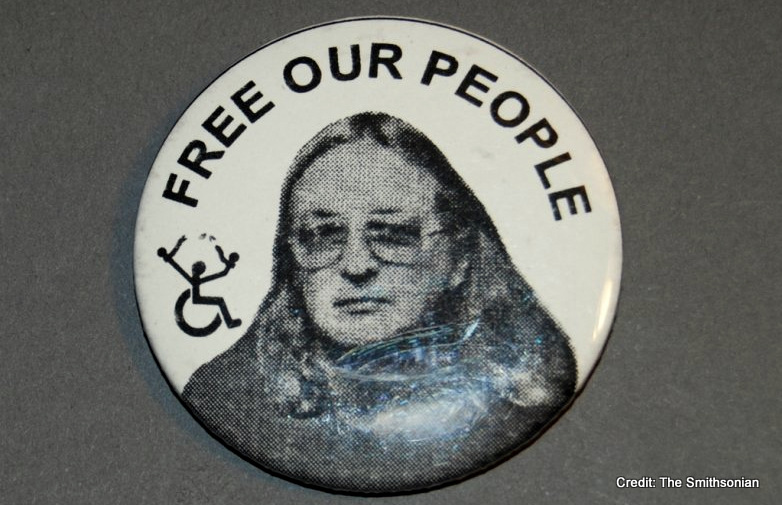

Their slogan is simple: “We’d rather go to jail than die in a nursing home.” But like so many other social justice issues, this struggle is about profiteering off the Americans most vulnerable with a powerful nursing lobby leading the effort to quash the disabled’s civil rights.

About one in five Americans have a disability and about 24.1 million are severely disabled. The New York Times recently reported that of the 1.4 million Americans in nursing homes, between 155,000 and 217,000 are good candidates to live independently.

The American Health Care Association, which has some of the deepest pockets in the nursing home industry, spent $968,000 on lobbying as of April this year, according to Opensecrets.org, a project of the Center for Responsive Politics. The policies they support force thousands into institutions that could live independent lives, and keeps wages low for the personal care attendants that help the disabled live in their communities.

Some were born with disabilities that limit their mobility or motor control, while others have been disabled by medical conditions, strokes or even car accidents. And, as the population ages, more and more people will need help to remain in their homes.

However, the Disability Integration Act, a bill sponsored by Sen. Chuck Schumer from New York, could change lives by making access to community-based services a human right.

It’s a reform that’s been a long time in coming but, since the movement began, the disabled haven’t been afraid to take extreme measures to be heard. They’ve organized sit-ins and blockades of buses to get their message across, and dozens are routinely arrested at their annual protests in Washington.

The disability rights movement began in the 1960s, when Ed Roberts, a quadriplegic man, became the first severely disabled student to attend from the University of California at Berkeley. As a student, he began organizing support services and housing that opened the door to other disabled students. In 1972, he helped found the first Center for Independent Living, a model for helping disabled people live independently still used worldwide.

One of the most effective disability rights groups active today, ADAPT, traces its origins to 1983, when Rev. Wade Blank, a former civil rights activist, helped a group of disabled people in a Denver nursing home create accessible housing. Years of direct action pressured the government to pass the Americans with Disability Act in 1990, and transit systems everywhere adopted wheelchair lifts thanks to the work of groups like ADAPT.

Although the ADA requires states to offer services to the disabled, it left the door open for the powerful nursing home lobby to collect more federal funding while essentially imprisoning the disabled. Many, especially those on Medicaid, are allowed extremely limited freedom, strictly confined to institutions for all but one or two days a week.

Accessible communities became the next goal of the movement. Throughout the 26 years since the passage of the ADA, ADAPT and their allies have protested in Washington and in their home states. They’ve even targeted the annual convention of the American Health Care Association, taking over meeting spaces and their hotel.

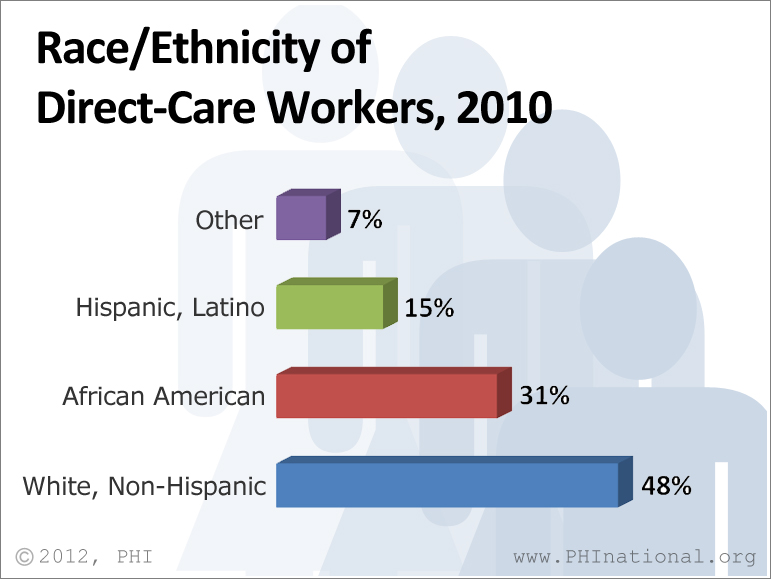

The Disability Integration Act would mandate that states provide more accessible housing and funding for personal care attendants who help with everyday tasks like cooking and bathing. Last year in Texas, which pays some of the country’s lowest wages to attendants, disability rights and labor activists occupied the governor’s office but only succeeded in raising base wages to $8.00 an hour. Under the DIA, states would also be forced to pay living wages for those attendants, who are overwhelmingly female and mostly minorities.

The current makeup of Congress leaves activists fighting an uphill battle for passage of bills like the DIA. A lot is riding on the next election, which could shake up both the House and the Senate.

Of course, about $452,000 of American Health Care Association spending went directly to congressional candidates, and was almost evenly split between both parties. So, regardless of whether seats are occupied by Democrats or Republicans, they’ll likely be taking money from the nursing home lobby. Maybe that’s why groups like ADAPT focus more on issues than on candidates and political parties.

These are human lives, and the stakes are high. Whether or not a bill like the DIA becomes law this year or years from now, it’s safe to say that disabled people will continue in their own civil rights movement — even if it means risking jail time, even if the public isn’t paying much attention.

Learn more about The Disabled’s Hidden Civil Rights Movement, Seeking Justice 32 yrs After Bhopal & Hemp’s Comeback: