At around 11 o’clock that night, four Lockheed MC-130 Combat Talons, turboprop Special Operations aircraft, were flying through a moonless sky from Pakistani into Afghan airspace. On board were 199 Army Rangers with orders to seize an airstrip. One hundred miles to the northeast, Chinook and Black Hawk helicopters cruised through the darkness toward Kandahar, carrying Army Delta Force operators and yet more Rangers, heading for a second site. It was October 19, 2001. The war in Afghanistan had just begun and U.S. Special Operations forces (SOF) were the tip of the American spear.

Those Rangers parachuted into and then swarmed the airfield, engaging the enemy — a single armed fighter, as it turned out — and killing him. At that second site, the residence of Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar, the special operators apparently encountered no resistance at all, even though several Americans were wounded due to friendly fire and a helicopter crash.

In 2001, U.S. special operators were targeting just two enemy forces: al-Qaeda and the Taliban. In 2010, his first full year in office, President Barack Obama informed Congress that U.S. forces were still “actively pursuing and engaging remaining al-Qaeda and Taliban fighters in Afghanistan.” According to a recent Pentagon report to Congress, American troops are battling more than 10 times that number of militant groups, including the still-undefeated Taliban, the Haqqani network, an Islamic State affiliate known as ISIS-Khorasan, and various “other insurgent networks.”

After more than 16 years of combat, U.S. Special Operations forces remain the tip of the spear in Afghanistan, where they continue to carry out counterterrorism missions. In fact, from June 1st to November 24th last year, according to that Pentagon report, members of Special Operations Joint Task Force-Afghanistan conducted 2,175 ground operations “in which they enabled or advised” Afghan commandos.

“During the Obama administration the use of Special Operations forces increased dramatically, as if their use was a sort of magical, all-purpose solution for fighting terrorism,” William Hartung, the director of the Arms and Security Project at the Center for International Policy, pointed out. “The ensuing years have proven this assumption to be false. There are many impressive, highly skilled personnel involved in special operations on behalf of the United States, but the problems they are being asked to solve often do not have military solutions. Despite this fact, the Trump administration is doubling down on this approach in Afghanistan, even though the strategy has not prevented the spread of terrorist organizations and may in fact be counterproductive.”

Global Commandos

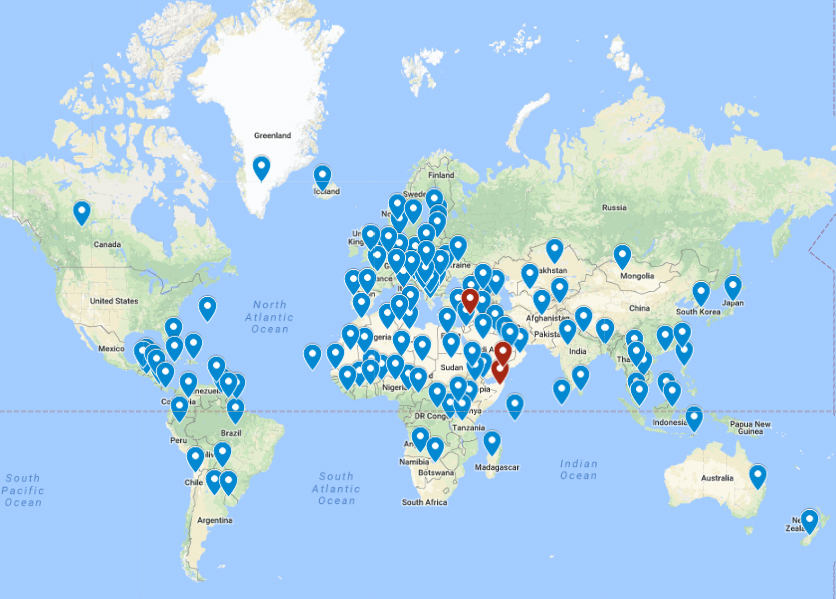

Since U.S. commandos went to war in 2001, the size of Special Operations Command has doubled from about 33,000 personnel to 70,000 today. As their numbers have grown, so has their global reach. As TomDispatch revealed last month, they were deployed to 149 nations in 2017, or about 75% of the countries on the planet, a record-setting year. It topped 2016’s 138 nations under the Obama administration and dwarfed the numbers from the final years of the Bush administration. As the scope of deployments has expanded, special operators also came to be spread ever more equally across the planet.

In October 2001, Afghanistan was the sole focus of commando combat missions. On March 19, 2003, special operators fired the first shots in the invasion of Iraq as their helicopter teams attacked Iraqi border posts near Jordan and Saudi Arabia. By 2006, as the war in Afghanistan ground on and the conflict in Iraq continued to morph into a raging set of insurgencies, 85% of U.S. commandos were being deployed to the Greater Middle East.

As this decade dawned in 2010, the numbers hadn’t changed appreciably: 81% of all special operators abroad were still in that region.

Eight years later, however, the situation is markedly different, according to figures provided to TomDispatch by U.S. Special Operations Command. Despite claims that the Islamic State has been defeated, the U.S. remains embroiled in wars in Iraq and Syria, as well as in Afghanistan and Yemen, yet only 54% of special operators deployed overseas were sent to the Greater Middle East in 2017. In fact, since 2006, deployments have been on the rise across the rest of the world. In Latin America, the figure crept up from 3% to 4.39%. In the Pacific region, from 7% to 7.99%. But the striking increases have been in Europe and Africa.

In 2006, just 3% of all commandos deployed overseas were operating in Europe. Last year, that number was just north of 16%. “Outside of Russia and Belarus we train with virtually every country in Europe either bilaterally or through various multinational events,” Major Michael Weisman, a spokesman for U.S. Special Operations Command Europe, told TomDispatch. “The persistent presence of U.S. SOF alongside our allies sends a clear message of U.S. commitment to our allies and the defense of our NATO alliance.” For the past two years, in fact, the U.S. has maintained a Special Operations contingent in almost every nation on Russia’s western border. As Special Operations Command chief General Raymond Thomas put it last year, “[W]e’ve had persistent presence in every country — every NATO country and others on the border with Russia doing phenomenal things with our allies, helping them prepare for their threats.”

Africa, however, has seen the most significant increase in special ops deployments. In 2006, the figure for that continent was just 1%; as 2017 ended, it stood at 16.61%. In other words, more commandos are operating there than in any region except the Middle East. As I recently reported at Vice News, Special Operations forces were active in at least 33 nations across that continent last year.

The situation in one of those nations, Somalia, in many ways mirrors in microcosm the 16-plus years of U.S. operations in Afghanistan. Not long after the 9/11 attacks, a senior Pentagon official suggested that the Afghan invasion might drive militants out of that country and into African nations. “Terrorists associated with al-Qaeda and indigenous terrorist groups have been and continue to be a presence in this region,” he said. “These terrorists will, of course, threaten U.S. personnel and facilities.”

When pressed about actual transnational dangers, that official pointed to Somali militants, only to eventually admit that even the most extreme Islamists there “really have not engaged in acts of terrorism outside Somalia.” Similarly, when questioned about connections between Osama bin Laden’s core al-Qaeda group and African extremists, he offered only the most tenuous links, like bin Laden’s “salute” to Somali militants who killed U.S. troops during the infamous 1993 Black Hawk Down incident.

Nonetheless, U.S. commandos reportedly began operating in Somalia in 2001, air attacks by AC-130 gunships followed in 2007, and 2011 saw the beginning of U.S. drone strikes aimed at militants from al-Shabaab, a terror group that didn’t even exist until 2006. According to figures compiled by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, the U.S. carried out between 32 and 36 drone strikes and at least 9 to 13 ground attacks in Somalia between 2001 and 2016.

Last spring, President Donald Trump loosened Obama-era restrictions on offensive operations in that country. Allowing U.S. forces more discretion in conducting missions there, he opened up the possibility of more frequent airstrikes and commando raids. The 2017 numbers reflect just that. The U.S. carried out 34 drone strikes, at least equaling if not exceeding the cumulative number of attacks over the previous 15 years. (And it took the United States only a day to resume such strikes this year.)

“President Trump’s decision to make parts of southern Somalia an ‘area of active hostilities’ gave [U.S. Africa Command or AFRICOM] the leeway to carry out strikes at an increased rate because it no longer had to run their proposed operations through the White House national security bureaucratic process,” said Jack Serle, an expert on U.S. counterterrorism operations in Somalia. He was quick to point out that AFRICOM claims the uptick in operations is due to more targets presenting themselves, but he suspects that AFRICOM may be attempting to cripple al-Shabaab before an African Union peacekeeping force is withdrawn and Somalia’s untested military is left to fight the militants without thousands of additional African troops.

In addition to the 30-plus airstrikes in 2017, there were at least three U.S. ground attacks. In one of the latter, described by AFRICOM as “an advise-and-assist operation alongside members of the Somali National Army,” Navy SEAL Kyle Milliken was killed and two U.S. personnel were injured during a firefight with al-Shabaab militants. In another ground operation in August, according to an investigation by the Daily Beast, Special Operations forces took part in a massacre of 10 Somali civilians. (The U.S. military is now investigating.)

As in Afghanistan, the U.S. has been militarily engaged in Somalia since 2001 and, as in Afghanistan, despite more than a decade and a half of operations, the number of militant groups being targeted has only increased. U.S. commandos are now battling at least two terror groups — al-Shabaab and a local Islamic State affiliate — as drone strikes spiked in the last year and Somalia became an ever-hotter war zone. Today, according to AFRICOM, militants operate “training camps” and possess “safe havens throughout Somalia [and] the region.”

“The under-reported, 16-year U.S. intervention in Somalia has followed a similar pattern to the larger U.S. war in Afghanistan: an influx of special forces and a steady increase in air strikes has not only failed to stop terrorism, but both al-Shabaab and a local affiliate of ISIS have grown during this time period,” said William Hartung of the Center for International Policy. “It’s another case of failing to learn the lessons of the United States’ policy of endless war: that military action is as likely or more likely to spark terrorist action as to reduce or prevent it.”

Somalia is no anomaly. Across the continent, despite escalating operations by commandos as well as conventional American forces and their local allies and proxies, Washington’s enemies continue to proliferate. As Vice Newsreported, a 2012 Special Operations Command strategic planning document listed five prime terror groups on the continent. An October 2016 update counted seven by name — the Islamic State, Ansar al-Sharia, al-Qaida in the Lands of the Islamic Maghreb, al-Murabitun, Boko Haram, the Lord’s Resistance Army, and al-Shabaab — in addition to “other violent extremist organizations.” The Pentagon’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies now offers a tally of 21 “active militant Islamist groups” on the continent. In fact, as reported at The Intercept, the full number of terrorist organizations and other “illicit groups” may already have been closer to 50 by 2015.

Saving SOF through Proxy War?

As wars and interventions have multiplied, as U.S. commandos have spread across the planet, and as terror groups have proliferated, the tempo of operations has jumped dramatically. This, in turn, has raised fears among think-tank experts, special ops supporters, and members of Congress about the effects on those elite troops of such constant deployments and growing pressure for more of them. “Most SOF units are employed to their sustainable limit,” General Thomas told members of Congress last spring. “Despite growing demand for SOF, we must prioritize the sourcing of these demands as we face a rapidly changing security environment.” Yet the number of countries with special ops deployments hit a new record last year.

At a November 2017 conference on special operations held in Washington, influential members of the Senate and House Armed Services Committees acknowledged growing strains on the force. For Jack Reed, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Armed Services Committee, the solution is, as he put it, “to increase numbers and resources.”

While Republican Senator Joni Ernst did not foreclose the possibility of adding to already war-swollen levels of commandos, she much prefers to farm out some operations to other forces: “A lot of the missions we see, especially if you… look at Afghanistan, where we have the train, advise, and assist missions, if we can move some of those into conventional forces and away from SOF, I think that’s what we need to do.” Secretary of Defense James Mattis has already indicated that such moves are planned. Leigh Claffey, Ernst’s press secretary, told TomDispatch that the senator also favors “turning over operations to capable indigenous forces.”

Ernst’s proxies approach has, in fact, already been applied across the planet, perhaps nowhere more explicitly than in Syria in 2017. There, SOCOM’s Thomas noted, U.S. proxies, including both Syrian Arabs and Kurds, “a surrogate force of 50,000 people… are working for us and doing our bidding.” They were indeed the ones who carried out the bulk of the fighting and dying during the campaign against the Islamic State and the capture of its capital, Raqqa.

However, that campaign, which took back almost all the territory ISIS held in Syria, was exceptional. U.S. proxies elsewhere have fared far worse in recent years. That 50,000-strong Syrian surrogate army had to be raised, in fact, after the U.S.-trained Iraqi army, built during the 2003-2011 American occupation of that country, collapsed in the face of relatively small numbers of Islamic State militants in 2014. In Mali, Burkina Faso, Egypt, Honduras, and elsewhere, U.S.-trained officers have carried out coups, overthrowing their respective governments. Meanwhile, in Afghanistan, where special ops forces have been working with local allies for more than 15 years, even elite security forces are still largely incapable of operating on their own. According to the Pentagon’s 2017 semi-annual report to Congress, Afghan commandos needed U.S. support for an overwhelming number of their missions, independently carrying out only 17% of their 2,628 operations between June 1, 2017, and November 24, 2017.

Indeed, with Special Operations forces acting, in the words of SOCOM’s Thomas, as “the main effort, or major supporting effort for U.S. [violent extremist organization]-focused operations in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, Libya, across the Sahel of Africa, the Philippines, and Central/South America,” it’s unlikely that foreign proxies or conventional American forces will shoulder enough of the load to relieve the strain on the commandos.

Bulking up Special Operations Command is not, however, a solution, according to the Center for International Policy’s Hartung. “There is no persuasive security rationale for having U.S. Special Operations forces involved in an astonishing 149 countries, given that the results of these missions are just as likely to provoke greater conflict as they are to reduce it, in large part because a U.S. military presence is too often used as a recruiting tool by local terrorist organizations,” he told TomDispatch. “The solution to the problem of the high operational tempo of U.S. Special Operations forces is not to recruit and train more Special Operations forces. It is to rethink why they are being used so intensively in the first place.”

Nick Turse is the managing editor of TomDispatch, a fellow at the Nation Institute, and a contributing writer for the Intercept. His website is NickTurse.com.

Follow TomDispatch, where this article first appeared, on Twitter and join them on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power, as well as John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II, John Feffer’s dystopian novel Splinterlands, Nick Turse’s Next Time They’ll Come to Count the Dead, and Tom Engelhardt’s Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.