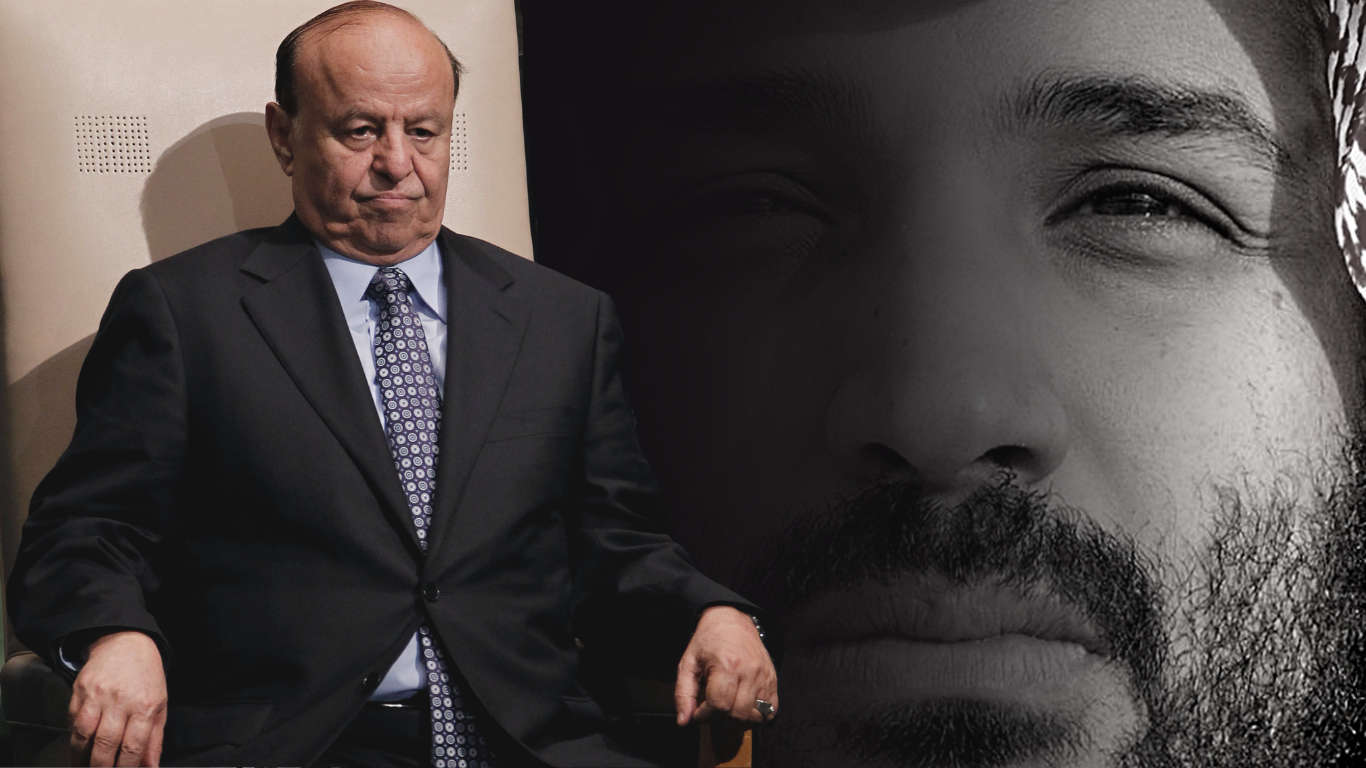

SANA’A, YEMEN – In perhaps the most significant political shake-up since 2015, Saudi Arabia and its Western allies have finally abandoned and ousted Yemeni President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi. On April 7, Hadi used his presidential authority to sign power over to an eight-man body known officially as the Presidential Command Council (PCC). The Saudi-led Coalition launched its brutal military campaign in Yemen in 2015 to restore Hadi to power following his ouster on the heels of Yemen’s Arab Spring popular protests.

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, de facto ruler of the Kingdom, has long been seen as the true power behind Hadi, who has been forced to rule Yemen in absentia from Riyadh for eight years. Bin Salman made a very public spectacle of Hadi’s ouster, as Hadi dismissed his vice president, Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, and then himself, handing over all his powers to the new presidential council. The choreography was similar to that presented by former Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri when he was forced to resign in November 2017 in a statement broadcast by a Saudi-owned TV channel. “I irreversibly delegate to this presidential leadership council my full powers,” Hadi said as he read a written statement in a televised speech.

MintPress News asked Yemeni citizens and decision-makers to react to the news that “the top of Yemen’s internationally recognized government” was no longer in power and what it could mean for the future of the war-torn country.

Fadl Abass, a Yemeni researcher who lost his son in the war, said of the news:

Getting rid of Hadi proved to us that the president’s value as president was solely to provide cover as he destroyed his [own] country for Saudi-led Coalition interests. And when the Saudis had enough of Hadi, they simply replaced him, regardless of the legality.”

In fact, a majority of Yemenis throughout the country celebrated the removal of Hadi, who was widely mocked as a Saudi puppet and yes-man. In Sana’a and across the northern stretches of the country controlled by the Ansar Allah coalition, people celebrated the news as a victory for Yemen’s Ansar Allah-led resistance movement.

Ansar Allah’s backers not only see Hadi as a traitor who supported the invasion of his own country and caused its destruction, but also believe that his end was spurred by recent Ansar Allah-led attacks on Saudi oil facilities. Some believe that the timing of Hadi’s ouster could be a sign that the Kingdom is growing frustrated as it fails to show any real return on its massive investment in Yemeni proxy groups that have failed not only to secure ground in Yemen but even to prevent costly attacks on the Kingdom itself.

Even those who supported Hadi and voted for him in 2012, and still consider themselves allies to Saudi Arabia, applauded Hadi’s dismissal. They see the move as a step to rearrange and organize the ranks of anti-Ansar Allah forces and, as one put it, “the most serious attempt in years to resolve the internal and external sources of division that have crippled the government’s policies and performance.” In the early days of the war, Saudi Arabia was able to attribute its military and political failure to Hadi. They openly blamed him for the victories of the “Houthis” and the sharp divisions within the ranks of his hodgepodge of mercenary groups. Now, they hope that the new Presidential Council can change the balance of power on the ground in the Kingdom’s favor.

Still, others have condemned the Saudi government for forcing Hadi to give up his office, especially members of the UAE-backed Islah Party, the Yemen-based branch of the Muslim Brotherhood. Islah member Tawakkol Karman, a well-known Yemeni activist and Nobel Prize winner, said that the legitimacy of the Saudi war ended with Hadi’s dismissal. Islah was not only denied a seat on the Presidential Command Council but lost an important ally in Vice President al-Ahmer.

If there is one aspect of Hadi’s humiliating ouster that all of Yemen’s myriad political interests seem to agree on, it’s that Hadi, as a Yemeni citizen, should never have been subjected to the sort of public humiliation he faced at the hands of the Saudi monarchy.

In quintessential Saudi fashion, Hadi’s removal came with an influx of cash. Namely, $3 billion to support “Yemen’s war-ravaged” economy – $2 billion of which will come from Riyadh and $1 billion from the UAE. According to Saudi sources, the money is aimed at “unifying the army, modernizing the doctrine of combat, ending divisions within the forces, combating terrorism and ratifying agreements without the approval of the House of Representatives.” In plain terms, the cash represents an attempt to offset any loss of influence posed by Hadi’s removal by assuring that any opposition to Ansar Allah remains well-funded and viable, a last-ditch hedge against the unfettered growth of the Kingdom’s enemies in Yemen.

The latest puppet

Chosen to head the Presidential Command Council, Rashad al-Alimi, Hadi’s de facto replacement, is seen by most as yet another satellite of the Saudi regime. A former interior minister, al-Alimi has cultivated a close working relationship with both the Saudi and U.S. governments and has flirted with normalizing ties with Israel, a move vociferously opposed by the vast majority of Yemeni citizens. During 2014 UN-brokered peace talks, al-Alimi was the lone voice in Yemen’s delegation to agree to a proposal legalizing the U.S. military presence in Yemen.

The other seven members of the Council represent varied interests in Yemen’s anti-Ansar Allah alliance, including Saudi-allied militia leaders and provincial heads like Marib Governor Sultan al-Aradah and Giants Brigades Commander Abdelrahman Abou Zaraa.

Ansar Allah has made it clear that they reject the legitimacy of the Council, saying that its formation in Riyadh is illegal and a violation of the Yemeni constitution. Mohammed Abdulsalam, Ansar Allah’s chief negotiator, told MintPress:

These measures taken by the coalition of aggression have nothing to do with Yemen, or the country’s reconciliation, and have nothing to do with peace. Rather, it pushes towards escalation through regrouping scattered conflicting militias into one framework that serves the interests of the outside and the countries of aggression.”

When pressed on the legality of Council’s formation, Abdulsalam added:

Its procedures have no legitimacy and are issued by an illegitimate party and do not have any authority, neither constitutional nor legal, not even popular. They were issued outside Yemen in form and content. The Yemeni people are not concerned with what the outside decides in their internal affairs.”

Shaking up Team Saudi

The major political shake-up comes amid a fragile and oft-violated two-month truce and is ostensibly geared towards rapprochement with Ansar Allah as the group gains ground, and on the heels of a campaign to inflict economic pain on the Kingdom through the strategic targeting of its oil reserves.

According to Hadi, “the council will be tasked with negotiating with the Houthi [Ansar Allah] rebels for a permanent ceasefire.” Many in Yemen see the statement as little more than an about-face, viewing the fact that the Presidential Council was formed in Saudi Arabia under the supervision of the United States as indicative of an ulterior motive and likely an effort to reorganize the myriad parties that form the opposition to Ansar Allah. Those parties have been in disarray as the war drags into its seventh year, with each pursuing its own often divergent goals.

Ansar Allah points to the designation of al-Alimi as head of the Council as evidence of its true aims. A former interior minister, al-Alimi is known as a security and military expert and has an intimate knowledge of the security and military sites that fell into Ansar Allah’s hands after Hadi’s 2015 ouster. Ansar Allah has accused al-Alimi of providing the Saudis with coordinates for these sites since the onset of the war.

Moreover, observers note that because the Council is composed of rival warlords holding often-opposing political objectives, it likely has little staying power. In fact, Aidarous al-Zubaydi, one of the eight members of the Council, is a staunch advocate of the secession of southern Yemen and labels himself as the president of an independent southern state.

Indications on the ground suggest that, far from brokering peace, the Council’s first act is likely to be an escalation of violence. On Wednesday, the Council announced it was mobilizing fighters in a number of military sites that are under the control of the Saudi-led Coalition in southern Yemen. The efforts coincide with the launching of U.S. Naval patrols in the nearby Red Sea.

For its part, Ansar Allah considers the mobilization evidence that the Council was never interested in peace. “The American move in the Red Sea, in light of a humanitarian and military truce in Yemen, contradicts Washington’s claim that it supports the truce. It seeks to perpetuate the state of aggression and siege on Yemen,” Mohammed AbdulSalam, the official spokesman for Ansar Allah and the head Yemeni negotiator, wrote on Twitter.

Wasn’t propping up Hadi the war’s justification?

The coup against Hadi – long described by Riyadh and Western leaders as the only “legitimate” president of Yemen – and the creation of a ruling council by a foreign country not only violate democratic ideals and Yemen’s national sovereignty and dignity, they are also direct violations of Yemen’s constitution.

Yemeni legal experts told MintPress that, constitutionally, Hadi was supposed to submit his resignation to the House of Representatives. After its acceptance, his resignation would be considered valid, and therefore a new president would be chosen by Parliament in the case that elections could not be held because of the war.

If championing democracy were the true aim, the United States and its allies should have responded to the millions of demonstrators that took to the streets to demand the dismissal and trial of Hadi before the country devolved into war and thousands of innocent lives were lost, just as they did in Ukraine in 2014 and in many other countries that saw popular uprisings during the Arab Spring.

Many Yemenis who spoke to MintPress expressed disdain towards Western leaders and governments for turning a blind eye to Saudi policies and called out what they see as U.S hypocrisy for backing the undemocratic formation of the unelected Presidential Command Council, which they point out does not represent large segments of Yemen’s population.

Others voiced disdain towards Western nations for prolonging the war by arming the Saudi-led Coalition and failing to diplomatically hold it to account for its numerous human rights violations. The millions of tons of munitions that have been dropped on Yemen under the pretext of restoring Hadi’s legitimacy have taken the country back a hundred years and caused the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, with hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties.

The quiet end of Hadi’s reign after a decade of serving U.S and Saudi interests not only nullifies the legal justification of the war under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, but also reinforces the long-held belief among many in the Middle East that Western powers were never interested in democracy. Instead, they fuel war, use heads of state as casus belli, and then abandon them when they are no longer of use. Political analysts who spoke to MintPress, including Yemeni journalist Ahmed Al-Qantas, warned that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy should pay heed to Hadi’s fate.

Perpetuating a troubled history

Hadi was brought to power on February 12, 2012, in a referendum in which he was the only candidate. The move, which came as part of the aptly-named “Gulf Initiative,” was not intended to bring Hadi to the fore as a legitimate candidate per se, but rather as a useful stand-in to quell the popular Arab Spring uprisings in 2011 that called for an end to foreign tutelage. During the 2011 protests, the Saudi kingdom not only found itself at a deadlock when searching for solutions and alternatives to President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s rule but also found itself facing the rise of various grassroots resistance movements – particularly Ansar Allah.

Prior to his ascension, Hadi was well-known by Saudi Arabia as a yes-man and politically weak in his own right, tasked only with following protocol and far less charismatic than Saleh, with a rich history of working against his country’s interests. Moreover, close to the foreign ambassadors and intelligence agencies, he served as the deputy chief of staff of the armed forces in Southern Yemen during the outbreak of civil war in 1986. In the wake of defeat in the internecine fighting, South Yemen’s then-President Ali Nasser Mohammed escaped to Sana’a with thousands of loyalists, including Hadi.

In the civil war in May 1994, most of the region’s effective political and military leaders in the south were eliminated and power was secured by the Sana’a government. Saleh relied on numerous holdovers defeated in the 1986 civil war, including Hadi, to secure power over restive groups. In October 1994, Hadi was named vice president, seen as posing little threat to the absolute power of the president and a useful means to assure that the restive southern elites felt represented. He remained serving silently in the shadows for 18 years as Saleh’s vice president before being shoved into the limelight by the Saudi regime.

The Presidential Command Council is ostensibly playing the same role, unable or unwilling to learn from Hadi’s political faux pas. In their short time in power, they have not only empowered Saudi Arabia in its efforts to secure political control over Yemen, but are similarly opportunistic, without remorse or the desire to place their country’s interests first – falling headfirst, it seems, into the cursed history of Yemeni politics.

Feature photo | MintPress News | Associated Press

Ahmed AbdulKareem is a Yemeni journalist based in Sana’a. He covers the war in Yemen for MintPress News as well as local Yemeni media.