KARACHI, Pakistan — If the Sindh provincial government does not come through on its promises to UNESCO and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) regarding the conservation of one of the world’s largest necropolises soon, experts fear that the monuments at Makli Hills will be scratched off the World Heritage List and moved over to the List of World Heritage in Danger by February.

When the 2010 super floods hit, the structures in the ancient graveyard suffered extensive damage. This damage, however, wasn’t just from floodwaters, it was also caused by the over 400,000 people who camped at the site.

After realizing the damage done to the site that year, UNESCO issued its first of several warnings about Makli.

“We asked UNESCO for two years to ensure that no damage will come to Makli and the site will be preserved for future generations to appreciate,” said Qasim Ali Qasim, director of the Sindh provincial archeology department.

Yet more than two years have passed, and the Sindh government has little to show in the way of the “tangible results” it had promised for the ancient graveyard in Thatta, located about 98 kilometers from the southern port city of Karachi, that offers a chronicle of Sindh’s robust political and social life from the 14th to 18th centuries.

Maryam Nizam, an architect working with the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan, an historical and cultural preservation non-profit that started an on-site conservation program in 2013, said it would be a “huge embarrassment” if the Sindh government failed to address the recommendations made by UNESCO and ICOMOS.

“The ruins were inscribed in 1981 on the World Heritage List, but in the last 33 years nothing significant has been done to conserve this globally important site,” Nizam told MintPress News.

The site is protected under the Antiquities Act of 1975 and the Excavation and Exploration Rules of 1978, and the Sindh government is responsible for managing it, both financially and administratively. Prior to Pakistan’s transition toward decentralization over the past several years, culture and heritage protection and preservation were the responsibility of the central government.

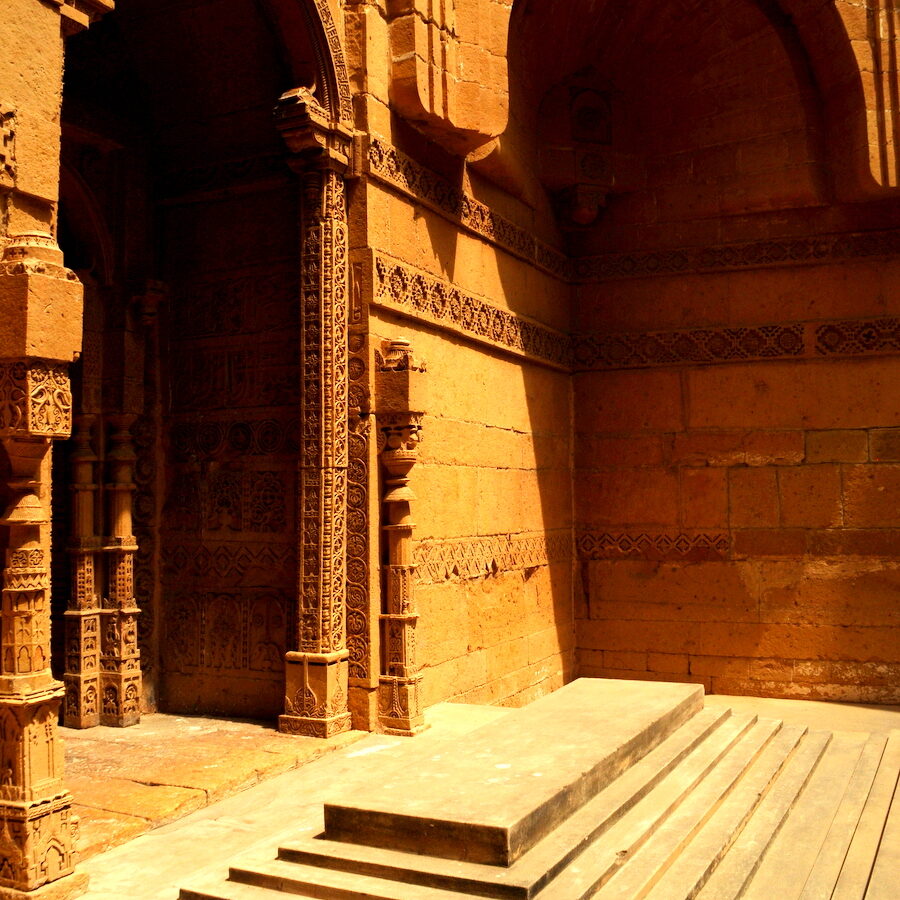

Spread over approximately 10 square kilometers, some half-million ancient local rulers and Sufi saints from the Sama period (1340-1520), the Arghuns (1520-1555), the Turkhans (1555-1592), and the Mughals (1592-1739) are buried at the necropolis. As the graves span four historical periods, there is great architectural diversity in the way they have been embellished, with touches of Hindu, Indo-Islamic, and even Central Asian cultures.

Last month the U.S. government pledged $26,000 under the Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation (AFCP) project to restore the 400-year-old Makli tombs of Sultan Ibrahim and Amir Sultan Muhammad.

“The AFCP is a centerpiece of America’s partnership with Pakistan in the area of art and culture,” said U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan Richard G. Olson at a ceremony held at the necropolis last month. “Our investments in these cultural preservation projects demonstrate our respect for the rich heritage and diversity of Pakistan.”

The Heritage Foundation of Pakistan will be implementing the project. In addition to carrying out conservation work on the two tombs, it will also focus on training local artisans, young architects and members of the provincial archeology department in the science and art of conservation.

“We will hold workshops in brick and lime-making, tile-making and stone carving. We also plan to engage with the local communities to not only make them aware of how encroachments ruin the site but what measures can be taken to stop further degradation,” said Nizam.

More than just conservation

“What’s gone is gone; it is thus important to remember the ruins must be treated as ruins and not made to look as rebuilt,” emphasized Yasmeen Lari, who heads the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan.

Speaking to MintPress, Lari said ethical guidelines need to be strictly followed by those taking up conservation projects for any cultural heritage site. “Conservation work should be based on evidence not conjecture. Intervention should be minimal. Methods employed [should be] reversible and include painstaking documentation and recording before, during and after conservation,” she explained.

UNESCO has suggested creating a basic site management plan, a master plan for on-site conversation, and a plan that would ensure a space for people displaced by natural disasters or severe weather events, like the 2010 super floods.

An outer boundary wall was also among the recommendations given by the international conservation agencies for a master and cultural management plan, which also included a disaster preparedness plan.

“We have already started constructing the wall, and by June 2015, that will be finished,” said Qasim, the chief archaeologist.

He told MintPress that the wall would prevent acts of vandalism as well as animal grazing and trespassing. Acknowledging that the government has not been able to honor all its commitments, Qasim said the major reason for this was the delay in the government’s release of roughly $3.9 million, which, in turn, led to the delay in implementing the management plan for the necropolis. “But I assure you, these ruins will not be put on UNESCO’s endangered list,” Qasim said confidently.

Meanwhile, the process of carrying out a comprehensive inventory of all structures, including logging appropriate documentation and historical information, is already underway, per the recommendation of the cultural preservation agencies.

With the help of the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan, the provincial archaeology department is currently preparing an inventory of all the ancient graves. “We have marked 477 standing monuments and platforms. Even old graves are being catalogued and their coordinates marked through GPS so that each and every one of these graves can be viewed via Google Maps,” said Qasim.

The foundation has completed documentation of 75 above-ground structures which Lari said “were in a highly degraded state.” Their most significant work has involved the preservation of the crumbling tomb of Samma Noble I through the Prince Claus Fund’s Cultural Emergency Response program. Work on that tomb was completed last year and handed over to the government for maintenance.

While working at the site, Lari noticed scores of new graves as well as shrines. “The new construction needs to be stopped immediately,” she said.

Alternatively, she suggested, “Maybe the archaeology department needs to allocate an area where the locals can bury their dead instead of burying them in the core zone, which is absolutely sacrosanct in terms of its heritage importance.”

One of the reasons for the rapid erosion, Qasim explained, is that Makli sits on a high plateau and wind carrying sandy particles has had a “boring effect” on the stone structures. Thus, the foundation feels that plantation along the outer boundary will help stop the strong winds from damaging the tombs and even possibly help prevent further soil erosion.

“Our research shows that in olden times, the place was lush green; we just need to find the right plants that can grow there,” said Nizam.

Qasim said most experts agree on this point, but there’s a problem: a 200-foot depression in the south means the trees must reach that height to be effective as a buffer.

According to Lari, the Makli site was once a popular picnic spot where people would come for recreation and pilgrimage. She hopes the place can come alive again.

“Nearly 80 percent of the master plan is ready and by the end of this month it should be ready, after which we will share it with international experts for their input,” Qasim said. In the meantime, he said to halt further deterioration, the government has started “Band-Aid” conservation efforts for some monuments before it can begin a systematic conservation program in Makli.

Pakistan is home to six World Heritage sites, all of which are in varying states of disrepair. There is no government-led organization that deals exclusively with the preservation and maintenance of World Heritage monuments, but UNESCO-sponsored preservation and conservation work has been carried out at these sites from time to time.

These sites include the Makli necropolis; the archaeological ruins of Taxila and Moenjodaro; the Buddhist ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and neighboring city remains at Sahr-i-Bahlol; the Rohtas Fort; and the Fort and Shalamar Gardens in Lahore. The latter two have already been declared endangered, and Makli will be Pakistan’s third World Heritage site to be declared endangered due to improper maintenance if measures are not taken soon.