(CONNECTICUT) — We don’t know why gunman Wade Michael Page entered a Sikh temple over the weekend and shot to death six people and wounded three others, including a police officer assisting a victim, in Oak Creek, Wis. And perhaps we will never know. Page is among the dead.

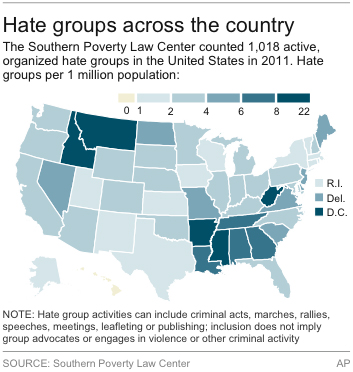

There are faint clues. Page’s body was festooned with tattoos, many suggesting a dedication to white-power ideology. He was also a member of the Hammerskins, a highly organized white supremacy group, according to the Anti-Defamation League, and he was the lead songwriter in a white-power metal band called End Apathy, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups.

For these reasons, and because the victims were Sikhs, a religious and ethnic minority in the U.S., law enforcement agencies, including the FBI, are saying this might satisfy the criteria for domestic terrorism. The FBI defines that as “the unlawful use of force or violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives.” Key to that designation, however, is Page’s motive, and as I say, we may never know what he hoped to achieve.

But does intent matter so much in a case like this? Terror has come down on Oak Creek, just as it did on Aurora, Colo. just over two weeks ago. In both places, a lone gunman opened fire on unsuspecting victims, families lost loved ones, survivors were traumatized for life and civic and religious institutions were shaken to their cores. If the Oak Creek case is terrorism — and, yes, it looks like it to me — then surely Aurora counts as terrorism, too. James Holmes, the only suspect in the that massacre, looked cartoonish in wild red Joker hair, but that shouldn’t exclude him from qualifying as a domestic terrorist.

Similarities and differences of the shooters

Let’s compare. Holmes was armed with assault rifles, head-to-toe body armor, a gas mask and tear gas. Page had just one gun, a 9mm with “multiple ammunition magazines.” Holmes planned his rampage. Page, as far as we know, didn’t plan his. One crime scene was a movie theater showing a midnight screening of a summer blockbuster. The other was a gurdwara, a holy gathering place for followers of Sikhism, a monotheistic faith younger than Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Holmes allegedly killed 12 people; for Page, half that. Holmes was afterward apprehended while sitting in his car while Page, after critically wounding one police officer, was shot down by another.

Both are white, male and young. Holmes is 24; Page was 40. Holmes was a former doctoral candidate in neuroscience. Page was a veteran of the U.S. Army discharged in 1998. Both used weapons purchased legally — and both acted alone. Neither had a serious criminal record.

A key difference between the shooters is that domestic terrorism was ruled out within hours of the Aurora slayings; Holmes had no ties to known terrorist organizations, the

FBI reported. But this presupposes that terrorists are social creatures when they often are anti-social. This solitary nature is what makes stopping them so difficult, according to a report by the Department of Homeland Security.

“Lone wolves,” the 2009 report says, pose the most significant threat of domestic terrorism, because they are not affiliated with formal organizations, “which hampers warning efforts.” The irony is that this Homeland Security report addressed the threat of right-wing extremism, i.e., white supremacy, among others, not a schizophrenic avatar of comic-book villains armed and armored to the teeth.

That’s just one irony. The other is that Page was being monitored by the FBI, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL). The FBI didn’t have enough information to conduct an investigation. The SPLC tracked his involvement in the white-power music scene. The ADL recorded the significance of his tattoos — the number “14” superimposed over an “Odin’s cross,” a Nazi death’s head and a Hammerskins tattoo. But none of this information helped authorities thwart mass murder.

Guns and terrorism

Even so, now we know Page was a racist with ties to hate groups. Now let’s ask: What difference does it make? The dead are still dead, right? To answer my own question, the difference might be that the rest of us don’t have to bother ourselves with a hard debate over guns.

Guns aren’t the problem, we say. It’s whack-job crazies like Holmes or radical extremists like Page who are the problem. Liberals and conservatives often say that only by changing our violent culture can we do something about the frequency of these destructive rampages.

To which I say: That’s a total cop out.

We can do something. First, call it what it is: terrorism. Intent is important, but not so much that it trumps consequences — the destruction of life and human kinship, a destabilized social order and an undermined public trust. Tattoos don’t make a terrorist as much as mass killings do.

Second, calling it terrorism might act as a deterrent.

Among Page’s many tattoos was a commemoration of the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. Since that horrible day, many of the nation’s 500,000 Sikhs have reported increased hostility, probably because the Sikh custom of wearing turbans (to hold a man’s hair, which is never cut) fits the racist stereotype of a bomb-throwing terrorist. Page might have thought he was attacking Muslims. In any case, a terrorist label acts to undermine the flawed notion that he was seeking revenge. Calling him a terrorist also means he is like Osama bin Laden, a potent deterrent to anyone who believes Page went out in a blaze of glory.

What needs to change?

Dawinder S. Sidhu, a law professor at the University of New Mexico, writes that all potential shooters, whether he’s a white supremacist, should feel the impact of our societal condemnation of terrorism.

To be sure, Mr. Holmes; Jared Lee Loughner, who is charged in the shooting that seriously wounded Rep. Gabrielle Giffords and killed six others; and Virginia Tech shooter Seung-Hui Cho were all loners and thus may have felt marginalized as is.

The “terrorist” label would, however, impose an additional social cost to their actions and may undermine any permanent legacy that such mass murderers are ostensibly seeking.

In failing to immediately and universally frame [the Aurora, Colo.] incident as terrorism, we failed to properly conceptualize what occurred, failed to hand down a swift and damning social sentence on the perpetrator, and failed to further disincentivize similar incidents.

Third, calling this terrorism can pave the way toward sensible federal gun-control legislation. President Barack Obama has already floated the idea that he is willing to revisit the ban on assault rifles, which was allowed to expire during the presidency of George W. Bush. If someone like Holmes wants to buy assault rifles, let’s at least not make it easy for him to do that. But that’s only the first step.

Even members of the National Rifle Association approve of background checks and firearms training. The president is taking the first step, and Congress, especially the Democrats, need to join him.

No politician would say there’s nothing we can do about terrorism. Aurora and Oak Creek were just that.

It’s time to stop blaming “culture” and do something.