While President Trump has recently hailed the defeat of ISIS, the group has been able to stave off a complete defeat by retreating to a few, small remaining pockets in Syria.

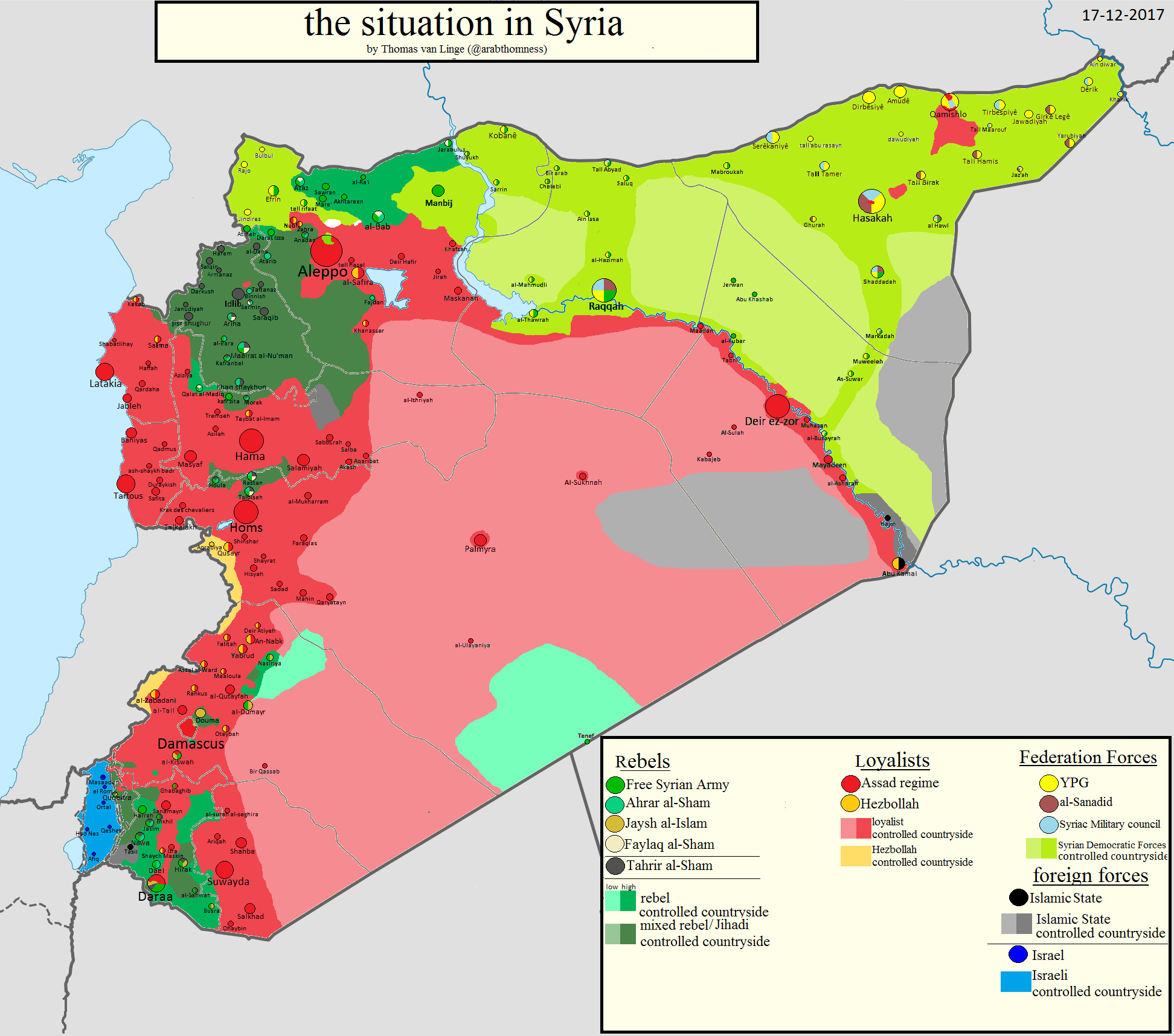

One of these pockets, located east of the Euphrates along Syria’s border with Iraq, is surrounded by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a grouping of Kurdish militias that are trained and armed by the U.S., and who act as the U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition’s leading partner in the fight against ISIS. And while the SDF and the coalition engage in battle with ISIS further south near Abu-Kamal, that is not the case in this pocket to the north. The fighters operating within this area do not have to fear coalition attacks or SDF assaults. Instead, they have been free to conduct their activities unimpeded, despite being surrounded by U.S. allies on the ground and U.S. aircraft overhead.

This is because the coalition has left this ISIS contingent alone — for months — as virtually no airstrikes have been carried out in the region since at least as far back as November of 2017. The few airstrikes that have been conducted since then, few enough to count on one hand, have not targeted ISIS fighters – save one.

This is the curious situation on the ground, which, despite a telling lack of reporting, has been maintained for months now. After the U.S.-backed SDF had encircled one of the last remaining pockets of ISIS fighters, the U.S. at the same time announced to Syria and its allies that it would prevent the Syrian Army from crossing into the U.S.’ self-declared “zone-of-control.” While actively blocking the Syrian Army – which was fighting ISIS on multiple fronts – from reaching this swath of territory, the coalition themselves have refused to attack it — for months. The picture that then emerges is one of an anti-ISIS coalition – one that has routinely expressed steadfast commitment to “annihilate” and “bring a lasting defeat” to ISIS – which has instead been effectively safeguarding one of the last ISIS strongholds still standing, as well as the ISIS fighters within it.

Refusal to strike

Although seemingly a remarkable situation, there is nothing in dispute about the facts regarding it. According to the official Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) reports, there have been virtually no strikes within this area, a stretch of land located between the city of al-Shaddadi and the Iraqi border, for the past few months.

The current situation began around mid-November 2017, following the SDF’s eviction of ISIS from their de-facto capital, Raqqa. The Syrian Army had at the time just broken a three-year-long siege by ISIS in the nearby Deir Ezzor, putting it in a position to retake the oil-rich surrounding regions. In light of this, according to a source present at the negotiations, the SDF began negotiations with ISIS to voluntarily give up Raqqa, because the U.S. “wanted a swift end to the Raqqa battle so the SDF could move on towards Deir al-Zor” before the Syrian Army was able to take it themselves.

Part of the deal stipulated that the evacuated fighters were to go and “prevent the regime’s advance” in that area. The oil-rich Deir Ezzor regions east of the Euphrates were in this way quickly swallowed up by the SDF. While the Syrian Army was then blocked from taking Deir Ezzor to the east of the Euphrates, it was able to establish its control to the west, while as well pushing on to take Abu-Kamal along the border, opening up a land route with Iraq. The Euphrates, therefore, served as the informal demarcation line between U.S. and Russian spheres of influence in Syria.

It was within this context that coalition airstrikes against the ISIS pocket east of the Euphrates trickled down to a near-complete halt. For example, the last OIR reported attack against ISIS fighters in the area in November was on the 11th, when “one strike” engaged “an ISIS tactical unit and destroyed an ISIS vehicle and a fighting position.” The next day “one strike” destroyed “an ISIS fighting position” but no fighters. For the rest of November there was only one remaining strike, conducted nearly two weeks later on the 24th, which only “damaged an ISIS supply route;” all other coalition attacks would be conducted elsewhere around Raqqa, Deir Ezzor, and Abu Kamal.

Much the same occurred in December. While “one strike” within the area on December 9 had indeed “engaged an ISIS mortar team,” this was to be the last of its kind. The first attack after this occurred on December 28, nearly three weeks later, when “one strike… destroyed a UAV [Unmanned Aerial Vehicle].” All others were confined to Abu Kamal and Al-Tanf further south. This continued into January.

All coalition strikes were conducted near Abu-Kamal save one on January 31, nearly a month after the last, which “destroyed a Daesh fighting position” but not any ISIS fighters. The reports available for February show the same picture. Abu Kamal is targeted, but nothing else.

What appears to be happening then is that, insofar as the area has been struck, it has been done so to establish “red-lines” that ISIS is not allowed to breach. This is the very strategy that was at first employed by former President Obama. Indeed, after the anti-ISIS campaign was launched, ISIS had grown in strength and territory, at least up until the time of the Russian intervention. This was because, according to research conducted by Durham University’s Dr. Christopher Davidson, ISIS was primarily fighting the U.S.’ enemies. “The Islamic State was effectively on the same side as the West,” Davidson writes, “especially in Syria, and in all its other warzones was certainly in the same camp as the West’s regional allies.”

Therefore the U.S. simply delineated boundaries around the group that it was not to cross, in places like Irbil and Kobane; and conducted limited strikes against “high-value targets.” The main task for the West, Davidson explains, was “trying to find the right balance between being seen to take action” while as well “still allowing the Islamic State to prosper,” and therefore weaken Syria and Iran militarily.

Official denials

Yet, according to the U.S., it is not tolerating any ISIS presence. Instead, the official story goes, ISIS “are more spread out and they are not as easy to target as if they were in a concentrated area” — this, of course, not explaining why the U.S. hadn’t attempted to target them in the first place.

Another argument has posited that the lenient situation has resulted mainly from the Turkish invasion, since the SDF has shifted its resources to reinforce Afrin. Yet Turkey’s “Olive Branch” operation only began very recently, as of January 20, while this coalition strategy has been employed as far back as November 2017.

Another explanation has tried to shift blame onto Syria — suggesting that ISIS has been able to move “with impunity through regime-held territory,” which shows that Syria “is either unwilling or unable to defeat [ISIS] within its borders.” This is plausible: after all, evidence has suggested that after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Syria had supported al-Qaeda-linked fighters that had crossed through Syrian territory to fight against the U.S. occupation.

It is reasonable to suspect that similar strategies would be employed now, as Syria finds itself under attack on multiple fronts. Indeed, according to researcher and Middle East Forum analyst Aymen Jawad al-Tamimi, such a strategy has been taken advantage of in Idlib, where fleeing ISIS fighters have recently found refuge, seemingly without any interdiction by Syrian authorities. “For the regime,” al-Tamimi said, “[ISIS] was useful in inflicting losses on HTS,” using an acronym for the al-Qaeda affiliate, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which controls that area.

There are also reasons to be skeptical about this narrative.

Related

- Operation Pacific Eagle: Duterte Falls in Line with US Plans for the Philippines

- ISIS and the US Could Turn the Philippines Into the Next Syria

- Kurds, Out of Options, Look to Syria’s Assad for Help

- How Did al Qaeda In Syria End Up With Anti-Aircraft Missiles?

- As The CIA Resumes Arming Rebels, Trump Escalates Proxy War In Syria

For example, it has been widely commented by prominent Western analysts that ISIS, as a Sunni extremist group, is mainly focused on attacking Shi’ites, meaning Iran and its allies. Importantly, this was also the reason these Sunni groups received funding and support from states like Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey, which exploited their anti-Assad and anti-Iran fundamentalism to help precipitate regime change in Syria. This activity was also enabled by the U.S., which sought to use ISIS’ insurgency as leverage to pressure Assad.

This identification of motive was further corroborated by an intensive research study from IHS Markit, which found that “Islamic State’s primary opponent in Syria is government forces,” ISIS having fought these forces “more than any other opponent.” This has also been pointed out by Max Abrahms, a counterterrorism expert and International Relations professor at Northeastern University, who argues that narratives about Assad not fighting ISIS are used by proponents of regime-change simply to help expedite the process.

It is therefore not surprising that one of the main reasons ISIS handed over some of the most strategically vital territory in Deir Ezzor to the SDF, according to the pro-opposition and Western-funded Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, was specifically that “ISIS prefer[s] handing over the organization-held areas to the SDF instead of handing them over to ‘the Shiite Militia,’ in order to prevent the regime forces from advancing towards these area[s].”

A regional campaign for influence

To be sure, the U.S. officials claiming that Syria allowed ISIS to move with impunity have themselves admitted that they “cannot confirm any alleged incidents or operations that are taking place outside our area of operations,” and have explained that if ISIS crossed Syrian territory it was a result of government forces being “too thinly stretched to keep ISIS in check.”

Yet this statement is also worrying.

The U.S. has, after all, clearly stated that its main interest in Syria is to roll back Iranian influence. While the arguments of Iran having taken over Damascus lack credibility, and are used to further justify the presence of the U.S. occupation, deep resentments do exist towards that country. This is due to the fact that Iran’s involvement played a crucial role in preventing the success of the U.S.-led regime-change project. Joshua Landis, Director of the Center of Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma, has explained the U.S. strategy is indeed premised upon an attempt “to hurt Iran and Assad” and to “deny Iran and Russia the fruits of their victory.”

In that sense, there exists an incentive for Syria and Iran’s enemies to exploit the fact that they are “too thinly stretched.” Perhaps it is not surprising then that coalition officials have stated they “will not carry out strikes against the militants’ [ISIS’] last remaining fighters as they move into areas held by the Assad regime” and that “there are no plans” to “stop remaining ISIS fighters moving into the west of Syria as they migrate along the Euphrates River Valley.”

The SDF have, after all, surrounded the ISIS pocket east of the Euphrates while the U.S. has told Syria and its allies they are not to cross into this U.S. zone-of-control. It appears, then, that as long as ISIS does not attack the SDF in the area, they will be protected from their “primary opponent” by this buffer, while also being free to move unimpeded, as long as they “move into the west of Syria” and fight in areas “held by the Assad regime.”

Indeed, according to fighters that are trained and supported by the U.S., this is exactly what is happening. According to the Financial Times, “some U.S.-backed opposition fighters and activists suspect their own side could be allowing small ISIS pockets to survive so they can attack and weaken the regime and its main backer in the region, Iran” — one of such fighters noting that “the Iranians practically controlled al-Bukamal. Now ISIS is taking over, all over again.” It seems then that “the [U.S.-led] coalition could use exterminating ISIS as an excuse to seek control of that whole area.”

The main point here is that, as long as Syria is in control of this Abu-Kamal area, it is therefore “off-limits” to the U.S.; attacking it would not be possible without a full declaration of war. Yet if ISIS can evict the Syrian forces themselves, then the possibility remains open for the U.S. to retake the area at a later time–at which point the elimination of ISIS could conveniently re-emerge as a strategic priority. This is particularly relevant in terms of Abu-Kamal because, as Joshua Landis has pointed out, the U.S. strategy is primarily directed towards blocking Syrian trade; evicting Syria from its only land-connection with its Iraqi neighbor would help serve this purpose.

Of legal necessity

Despite the U.S. announcing its plan to remain in Syria after ISIS is gone, it is still very much reliant on ISIS’ existence to justify this occupation. This is because the legal rationale the U.S. used to legitimate its military activities that are being conducted on foreign soil without the consent of the Syrian government — and therefore to avoid being seen as committing an act of aggression against another state, the supreme crime under international law — was that it was there to help defeat ISIS. So, while the U.S. has been violating Syrian sovereignty and territorial integrity in the process, respect for which was required under the relevant UN Security Council resolutions, it was argued that, since ISIS threatens Iraq and the U.S. was invited in by the Iraqi authorities, it is therefore able also to pursue the group in Syria “in self-defense.” This is problematic for many reasons, but it served as the legal fig-leaf the U.S. was able to use to conduct its operations.

With ISIS gone, that legal rationale goes as well. In that sense, the Trump administration was caught between a rock and a hard place — at once needing to further its interest of occupying northeastern Syria, while at the same time needing ISIS to not completely be destroyed in order to do so. In that sense, it is worrying that U.S. officials have announced that they plan to remain in Syria “as long as they [ISIS] want to fight,” specifically justifying this on the grounds that “the enemy hasn’t declared that they’re done with the area yet.”

Concurrent with this, according to classified U.S. military and intelligence assessments, “thousands of Islamic State foreign fighters and family members have escaped the American-led military campaign in eastern Syria” — while other intelligence officers note an increase in fleeing ISIS fighters being smuggled into Turkey, “the exodus” of whom “began after Mosul [in Iraq] fell and continued after [ISIS] lost Raqqa.” Because of this, the problem has the potential not only to continue threatening Syrians but others abroad as well. Those with access to the assessments claim that “of more than 5,000 Europeans who joined [ISIS’] ranks, as many as 1,500 have returned home, including many women and children.”

It therefore appears that, by refusing to eliminate the ISIS contingent around which the SDF have established a buffer, while also not impeding the fighters fleeing westward, the anti-ISIS coalition, who profess their dedication “to prevent[ing] ISIS from exporting their terror around the world,” have not only not been helping to mitigate this outcome but have actually helped to enable it.

Cynical pursuit of geopolitical goals, hollow professions of concern

If this is indeed the case, it appears once again that power and hegemony have been prioritized at the expense of commonly professed interests such as counterterrorism and global safety. Professions of concern for civilian casualties and the victims of terrorism are useful ways to mobilize support for certain policies, but in reality they are not seriously considered. What matters to strategic planners is the furtherance of state-influence and control, and the rooting out of independence and those that rival the power’s hegemony.

Therefore, groups like ISIS are not seen as something to be immediately destroyed but rather as an opportunity. The universal public outrage and calls for action that result from their atrocities can conveniently be corralled into a justification for establishing a foreign military presence that would not have been possible otherwise. In the same sense, since “the Islamic State was effectively on the same side as the West,” its ruthless battlefield tactics could serve as an important short-term asset by helping to guarantee a strategic outcome inside Syria that maximizes U.S. control and influence and minimizes that of its rivals.

In the longer-term, the continued presence of the Islamic State is a necessary condition to avoid being categorized as an invading force and to maintain the legal relevance of the U.S. occupation.

Far from being outside the bounds of consideration, these motivations were recently summarized by the foreign minister of the U.K., who explained how, at times:

a government or its agents will covertly support terrorist groups abroad: either to weaken that government’s neighbors … or, most destructively of all, … to engage in a regional campaign for influence by exploiting the weaknesses of states, and by promoting fanatical or semi-fanatical militias to force other states to respond.”

When media and citizenry alike decline to confront these unsavory and uncomfortable realities, a smokescreen of impunity is permitted to develop around government actions, allowing such strategies to be utilized without repercussion. And while — as Zbigniew Brzezinski, the former National Security Advisor to President Carter, has commented — “the pursuit of power is not a goal that demands popular passion” among the public, it is alive and well in the minds of planners. Crucially, however, these pursuits of power only “remain strong when they remain in the dark” — as Samuel Huntington, former professor of Political Science at Harvard University, has described — and “when exposed to sunlight they begin to evaporate.”

Feature photo | A U.S.-backed anti-government fighter mans a heavy automatic machine gun, left, next to an American soldier as they take their positions at Tanf, a border crossing between Syria and Iraq (Hammurabi’s Justice News/AP)

Steven Chovanec is an independent journalist and analyst based in Chicago, Illinois. He has a bachelor’s degree in International Studies and Sociology from Roosevelt University and has written for numerous outlets including The Hill, TeleSur, MintPress News, Consortium News, and others. His writings can be found at undergroundreports.blogspot.com, follow him on Twitter @stevechovanec.