RIYADH — If Saudi Arabia anticipated its military campaign against rebellious Yemen to be swift and painless, little did the kingdom realize that such a decision would open the floodgates of dissent within its own borders.

Inspired by the rebellion of the Houthis of Yemen, the Sunni tribes of Najran, a province bordering Yemen in southwestern Saudi Arabia, renounced the authority of King Salman in June, declaring his rule illegitimate.

Beyond those regional collusions an opportunity has emerged that the United States could play to its advantage through the military and political exhaustion of a power which has become a nascent threat to America’s standing in Arabia.

Over the span of five months a mere exercise of power against an unruly neighbor whose political ambitions did not sit within Riyadh’s hegemonic ambitions, has devolved into an imperial war of survival fed by tribal defiance and geopolitical recalibration.

“What began as a war of political restoration in Yemen in late March has now turned into a war of attrition, but not necessarily in the direction most proponents expected,” Hasan Sufyani, a leading analyst at the Sana’a Institute for Arabic Studies, told MintPress News.

On the heels of Yemen’s once-resigned, twice–runaway President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi’s exile to Riyadh before the rising tide of the Houthi anti-imperialist movement, the kingdom unilaterally declared war on the impoverished nation on March 25, claiming it sought to restore Hadi’s legitimacy and thus enable Yemen to complete its Western-backed, Gulf Cooperation Council-brokered transition of power.

On March 28, the Independent reported that King Salman said: “A Saudi Arabia-led alliance is willing to wage a military campaign against Houthi rebels in Yemen for as long as it takes to defeat the Iranian-backed group that has forced the country’s president to flee.” From that point on the narrative of war was set within a rhetoric of legitimacy, with the Houthis claiming revolutionary popular support and Al Saud wielding its own brand of exceptionalism.

Commenting on this shift of power, which first manifested within Yemen as its people rallied behind the Houthis in response to Riyadh’s aggression and injunctions from Western powers to forfeit political self-determination to the realpolitik of neo-imperialism, Sufyani noted: “Yemen’s resolve and resilience before foreign aggression ignited the long dormant fire of Arab nationalism, stirring old regional allegiances and tribal loyalties.”

A tribal militia organized under the command of Sheikh Abdel-Malek Al Houthi, the Houthis are building a network of their own well outside the borders of their political dominion. This has prompted other factions to enter into a resistance movement of their own, while also giving foreign powers the gift of opportunity.

Sufyani explained:

“An arrow in the bow of Western imperialism, the House of Saud has long inspired disgust among the Arabs, even more so in the Peninsula, where its grip on power is most visible and suffocating. For all intents and purposes, the kingdom has become the embodiment of tyranny, whether political, religious or even economic. And so, when the Houthis came to oppose, resist and push back against Al Saud superpower, new political aspirations began to rise. Arabia is rising once more against the bedouins of Nejd.”

Bogged down in Yemen in a military standoff which has proven to be geographically uncontainable, the kingdom has also had to contend with a nascent sedition movement in its southern territories since the end of June.

In this battle of wills between a David and a Goliath, it could be that the rules of the haughty do not apply.

Enemies at the gate

“If the grand regional coalition Saudi Arabia called under its banner to tame Yemen was meant as a form of political posing to imply legitimacy, time certainly eroded at the fabric of such consensus, since Yemen proved a tough nut to crack,” suggests Mohammed Kleit, a Beirut-based journalist and political analyst specializing in the Arabian Peninsula.

Kleit argues that Saudi Arabia hopes to enroll other foreign powers in its military pursuit against Yemen — a grand show of force to belittle a vassal, which left it not only open for criticism but also politically exposed.

Kleit explained:

“Much of the political dynamics and alliances/allegiances in the Peninsula continue to be based on one power’s ability to manifest either force or financial coercion. So far, the Saudis have of course been able to wield both those attributes and therefore they remained in control and in the lead. Come now Yemen and its tribal militias. … The kingdom is no longer this immovable force Arabs have no recourse against.”

He added: “Alternatives are being explored and this is creating interesting developing dynamics, especially within the perimeters of a growing Shia-Islamic populist movement in the region — Bahrain, Iraq and evidently Yemen.”

As far as Yemen is concerned such “alternatives” came by way of military retaliations against the kingdom after the kingdom dared to cross swords with the sons of Hamdan. While Riyadh fired its missiles and reinforced its siege against Yemen’s coastline, and as famine and disease raised their specters before the unravelling humanitarian catastrophe media carefully shied away from covering, the Houthis brought war to Saudi Arabia by encroaching on its territories.

In a move which few could have anticipated, especially since Saudi Arabia made such a show of its border military mobilization, the Houthis, backed by Yemen’s army, led combat operations deep within the kingdom, shattering the Saudi sense of security.

As early as May, the war on Yemen became an only too tangible Saudi reality when rocket attacks and threats of further military escalation — quite literally — hit home. No longer a sitting duck, an increasingly bold Yemen chose to strike back.

And though Riyadh has been keen to play down Yemen’s ability to inflict harm, as suggested by a June 7 Bloomberg report of a foiled Scud attack on the kingdom, other outlets — mainly non-aligned media — have ventured into further detail when referring to Yemen’s advances in Saudi Arabia.

On June 20, Alalam reported an attack on a Saudi military base in the southern province of Jizan, making clear note of the destruction incurred. (Jizan, it should be noted, sits at the heart of a contentious territorial dispute between Yemen and Saudi Arabia.)

Speaking to MintPress in June, Andrew Bond, a political analyst with the Institute for Gulf Affairs, cautioned that the monarchy and Saudi Defense Minister Mohammed bin Salman, who also serves as deputy Crown Prince to the throne of his father, King Salman, are slowly losing face.

“The implications of a broad Houthi-led military campaign against the kingdom could lead to an acute political crisis within the royal family, as issues of legitimacy over the management of the affairs of the state might arise,” Bond noted.

Though little known to the public, the Houthis have a wealth of experience when it comes to “breaking into the kingdom.” Back in 2009, the Houthis managed to hold on to the city of Jizan long enough to negotiate a royal ransom. Shamefaced and under the cover of a well-orchestrated media blackout, the kingdom paid up and moved on.

With more than ransoms on their mind, Yemenis could attempt to venture further in into Saudi Arabia this time around, especially if local tribes prove welcoming.

The war within

While the kingdom devised a plan in March to return Yemen back to the monarchical fold, never did officials in Riyadh imagine the winds of dissent would blow from within, born out of a sense of solidarity with the Houthis’ plight.

If dissent and rebellion come easy for a Western public raised on pro-democracy movements and populist revolutions, rebellion is a less-than-natural state of mind for a people whose freedoms have always been stifled.

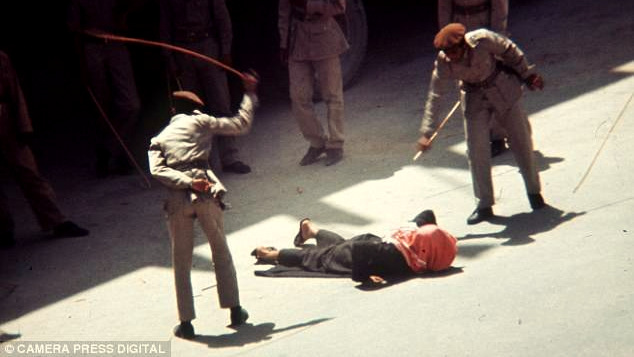

Arguably the most violent and reactionary theocracy in the world, Saudi Arabia’s totalitarian monarchy is also absolutely opposed to any form of political criticism. For those inquisitive minds which cannot bear to be confined to silence, Saudi officials invariably react by way of whip or death.

It is within this context of fear that Hasan Sufyani, the analyst from Yemen, explains how critical the rebellion of the tribes of Najran could prove to be in the “tumbling down of the Saudi monarchy.”

“Najran tribes have been incensed by Al Saud’s cruelty against Yemen. It has been felt deeply in Najran as old tribal ties unite its people to Yemen. Najranis still consider themselves Yemenis and therefore an attack on Yemen — northern Yemen, particularly — has struck a chord among many. To put it in very simple terms: the tribes of Najran want to see Al Saud gone,” Sufyani said.

In late June, the tribes of Najran, organized under the Ahrar al-Najran Movement, publicly announced their independence from Saudi Arabia. These southern tribes pointed to social injustice, poverty, repression, and discrimination as the roots of their ire against Al Saud.

Abu Bakr Abi Ahmed al-Salami, a leader of the movement, told reporters in June his group was gearing up for combat, ready to translate verbal sedition into an armed struggle.

Writing for New Eastern Outlook, Eric Draitser explains:

“Needless to say, from the perspective of the Saudis, a nascent independence movement within their borders is just about the worst possible outcome of their decision to wage war on Yemen. And considering the already tense situation in the majority Shia province of Qatif, it seems Saudi Arabia has become a political powder keg just waiting for a spark. Undoubtedly the Ansarullah Movement understands this perfectly well, and is now preparing to make its move, matches in hand.”

The tribes of Najran are not alone in their desire to break away from, if not altogether topple, the Saudi monarchy.

In the eastern province of Qatif, where humiliation and sectarian-based persecution are the norm, rights activists such as Hussein Jawad, a human rights advocate and general secretary of the European-Bahraini Organisation for Human Rights (EBOHR), have long warned that the status quo would only last for so long.

Commenting on what he understood as the premise of a Saudi revolutionary movement, Jawad told MintPress back in January how he “could see the people of Arabia unite against Al Saud under the right impetus.”

The enemy without

But what if this impetus came not from Yemen but further out, and not from a foe but a friend?

If, as Juan Cole argued in a piece for Foreign Policy in January, the troubles of Saudi Arabia’s absolutism are many and mostly born of its own brand of ascetic religious puritanism, Wahhabism, it may actually be the kingdom’s foreign policy failures which could ultimately trigger its demise.

Hasan Sufyani speculates that Al Saud could have fallen victim to “the syndrome of the first Gulf War,” when President Saddam Hussein led an armed invasion against Kuwait in 1990 to recover its alleged stolen oil under the premise that the U.S. would sit impartial.

“Looking at the region’s evolving geopolitical map and in view of Washington’s almost symptomatic paranoia at the idea foreign powers could attempt to rival its pull, then it could be assumed that Saudi Arabia’s military firepower build up grew to be a threat the U.S. needed to neutralize,” Sufyani said. “War has a way of levelling the field and forcing country to scale down.”

Sufyani’s theory is that the U.S. might have found in the kingdom’s war against Yemen an opportunity to reel its longstanding ally back within political and military parameters it feels comfortable with.

Whether through internal dissent, self-destruction or foreign intervention, it would appear the kingdom’s Doomsday clock is approaching midnight.

As Nassim Nicholas Taleb and Gregory F. Treverton explained earlier this year in Foreign Affairs: “Fragility has five principal sources: a centralized governing system, an undiversified economy, excessive debt and leverage, a lack of political variability, and no history of surviving past shocks.”

For Saudi Arabia, all five criteria have already been fulfilled.