What is your job worth? Any person lucky enough to have a full-time job in today’s world probably depends heavily on their salary, but the cost to their employer goes far beyond that — there are also benefits, like health care and retirement plans, and myriad taxes. The total cost of an employee is far more than pay, and it can roughly be called the “overhead per employee.”

By the simplest calculation, on average, the overhead per employee is more than 42 percent above what an employee takes home. This overhead is one of the biggest barriers to increasing employment, reducing hours and generally creating a better quality of life for working people in the United States. It also puts us at a competitive disadvantage when it comes to creating high-quality jobs.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics keeps track of the total cost of employees. It found that as of October 2013, an average worker in the U.S. makes $20.55 per hour, or about $42,700 per year. It’s not a lot, and it shows why so many families have to rely on two wage earners to live the American dream of owning a nice car, a large TV and other items.

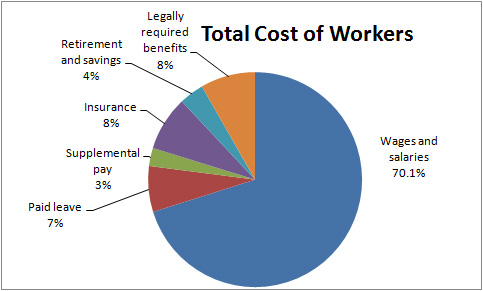

But their employer sees an average worker as costing much more than that. There is pay for vacations and sick time, retirement, health care, insurance against liability, as well as required contributions to social security, unemployment and worker’s compensation. Together, it adds up to $29.23 per hour, or nearly $62,900 per year.

Some of this cost scales with higher salary, but insurance and health care do not. All together, they represent a figure of the total overhead per employee that is close to the “time and a half” paid for overtime. That means that an employer with a highly variable need for workers during a year, such as a Christmas rush, or with costs slightly above average may see a net benefit to making employees work more than 40 hours a week rather than hiring more people.

While work flexibility has different definitions for employee and employer, it’s definitely desirable for both. With such high overhead, though, it is very expensive and difficult to provide. It’s also obvious why so many large companies are turning toward consultants and temporary employees — they do not carry as much overhead to get the job done — in order to have the flexibility they need. It’s a situation that needs to be corrected if we are going to have a flexible workforce that is capable of taking time off to take care for the kids and be a good citizen in the community.

As a matter of policy, the taxes for Social Security and Medicare — 7.62 percent of the first $117,000 of salary — along with worker’s compensation taxes seem like a good idea. They form a reliable pool of money that funds necessary social programs and does not need to be adjusted much year to year. These “payroll taxes,” however, represent a tax on employment, which is a terrible choice to make at a time when there is high unemployment and a need for more jobs.

The Social Security and Medicare taxes are collectively known as Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) of 1937. They are supposedly not a tax, but a contribution to a retirement system.

“The payroll tax does not operate like a benefits tax because the benefits received are not well correlated to the taxes paid,” according to Linda Sugin of the Fordham University School of Law in an article published in the Harvard Journal on Legislation.

The benefits do not go directly to the person paying in, but instead to a general pool. “Without clear allocation of benefits to individuals, the proper distribution of the tax burden is impossible to specify.”

It is a tax like any other, she concludes, except it is highly regressive.

“Payroll taxes are regressive: low- and moderate-income taxpayers pay more of their incomes in payroll tax than do high-income people, on average,” states the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The center’s figures also show that since 1945, payroll taxes have grown from 8 percent of total federal taxes collected to 36 percent today, increasing the regressivity of the whole tax system.

“Payroll taxes and corporate income taxes accounted for an equal share of federal tax revenue in 1969. By 2009, payroll taxes generated more than six times as much revenue. We’ve become reliant on payroll taxes, and a goal of a tax overhaul should be to reform and reduce them, permanently,” Owen Zidar, a doctoral candidate in economics, noted in a New York Times editorial.

The U.S. also has a somewhat unique system in which employers are stuck with the tab for health care, rather than taking it out of general taxes in a universal system. All of the developed and developing nations that our workers compete with for jobs operate under a universal health system, placing our workers at a competitive disadvantage.

Paul Krugman noted that advantage when Toyota chose to open a new plant in Ontario rather than the U.S. “Canada’s big selling point is its national health insurance system, which saves auto manufacturers large sums in benefit payments compared with their costs in the United States.”

Combined with the taxes on employment, this represents 15.5 percent of total compensation or half of the Bureau of Labor Statistics tracked overhead, on average. Changing these to systems that rely on taxes on corporate profits, for example, will be politically difficult but would help to dramatically improve the flexibility of the workforce.

One of the greatest barriers to creating more jobs in the U.S. is the very high overhead per employee. The workforce of tomorrow is going to have to be more flexible. That can be a very good thing for both employee and employer, but a lot is going to have to change to get to that point. A focus on reducing reliance on regressive payroll taxes combined with reducing the overhead per employee is a critical element for creating more and better jobs in the years ahead.