WASHINGTON – Amid tough talk from European and American leaders, a new MintPress study of our nation’s most influential media outlets reveals that it is the press that is driving the charge towards war with Russia over Ukraine. Ninety percent of recent opinion articles in The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal have taken a hawkish view on conflict, with anti-war voices few and far between. Opinion columns have overwhelmingly expressed support for sending U.S. weapons and troops to the region. Russia has universally been presented as the aggressor in this dispute, with media glossing over NATO’s role in amping tensions while barely mentioning the U.S. collaboration with Neo-Nazi elements within the Ukrainian ruling coalition.

Periodic hysteria

Western media and governments have expressed alarm over a suspected buildup of Russian military forces close to its over-1200-mile border with Ukraine. There are reportedly almost 100,000 troops in that vicinity, causing President Joe Biden to warn that this is “the most consequential thing that’s happened in the world in terms of war and peace since World War II.”

Yet this is far from the first media panic over a supposedly imminent Russian invasion. In fact, warning of a hot war in Europe is a near yearly occurrence at this point. In 2015, outlets such as Reuters and The New York Times claimed that Russia was massing troops and heavy firepower, including tanks, artillery and rocket launchers right on the border, while normally sleepy frontier towns were abuzz with activity.

In 2016 there was an even bigger meltdown, with media across the board predicting that war was around the corner. Indeed, The Guardian reported that Russia would soon have 330,000 soldiers on the border. Yet nothing came to pass and the story was quietly dropped.

With the next spring came renewed warnings of conflict. The Wall Street Journal claimed that “tens of thousands” of soldiers were being deployed to the border. The New York Times upped that figure to “as many as 100,000.” A few months later, U.S. News said that thousands of tanks were joining them.

In late 2018, The New York Times and other media outlets were again up in arms over a fresh Russian buildup, this time of 80,000 military units. And in the spring of last year, it was widely reported (for instance, by Reuters and The New York Times) that Russia had amassed armies totaling well over 100,000 units on Ukraine’s border, signaling that war was imminent.

Therefore, there are actually considerably fewer Russian units on Ukraine’s border than there were even 11 months ago, according to Western numbers. Furthermore, they are matched by a force of a quarter-million Ukrainian troops on the other side.

Thus, many readers will be forgiven for thinking it is Groundhog Day again. Yet there is something different about this time: coverage over the conflict has been enormous and has come to dominate the news cycle for weeks now, in a way it simply did not previously. The possibility of war has scared Americans and provoked calls for a far higher military budget and a redesign of American foreign policy to counter this supposed threat.

Russia, for its part, has repeatedly rejected all allegations that it plans to attack Ukraine, describing them as “fiction.” “Talks about the coming war are provocative by themselves. [The U.S.] seems to be calling for this, wanting and waiting for [war] to happen, as if you want to make your speculations come true,” said Russia’s ambassador to the United Nations, Vassily Nebenzia.

Perhaps more surprisingly, the Ukrainian government appears to agree, recognizing that any conflict would prove devastating to both the Russian and Ukrainian economies and that even the saber-rattling and prospect of such conflict is already having an impact on business and investment. “[W]e don’t see any grounds for statements about a full-scale offensive on our country,” said Oleksiy Danilov, the chief secretary of Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council. In an interview with the BBC, Danilov also revealed his exasperation with the media for unreasonably ginning up fears and tensions.

Searching NYT, WSJ, and WaPo

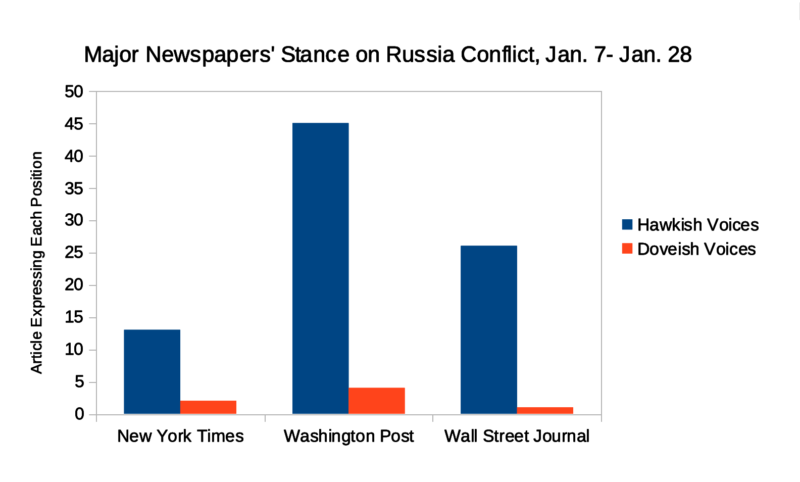

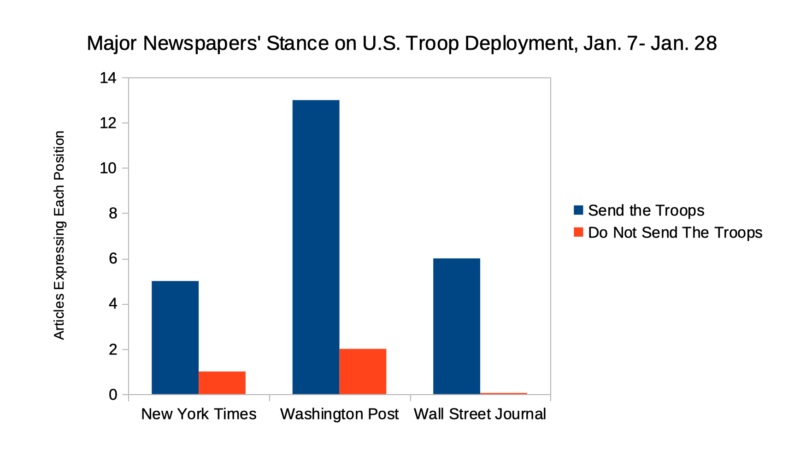

To test Danilov’s claim that Western media have been among the loudest voices cheering for war, MintPress conducted a study of three of the most prominent and influential American outlets: The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal. Together, these three outlets often set the agenda for the rest of the media system, and could be said to be a reasonable representation of the corporate media spectrum as a whole. Using the search term “Ukraine” in the Factiva global news database, all opinion pieces on the conflict published in the previous three weeks (Jan. 7 – Jan. 28) were read and studied. This gave a sample of 91 articles in total; 15 in the Times, 49 in the Post and 27 in the Journal. For full information and coding, see the attached viewable spreadsheet.

Overall, the tone from the three newspapers studied was exceedingly hawkish, with around 90% of the columns expressing a “get tough” message. There was little to no variation among the outlets in their tone. “[Russian President Vladimir] Putin aims beyond Ukraine. Checking him right now is crucial,” ran the headline of former general Wesley Clark’s Washington Post article. Columnist Max Boot claimed that Putin “definitely wants to resurrect the Soviet empire.” Boot’s colleague at the Post, Henry Olsen, launched a bitter attack on Biden for not being hawkish enough, describing the president as a weakling who is unfit to lead. Meanwhile, The Wall Street Journal took the opportunity to denounce the American left for focusing on non-existent U.S. imperialism when it should be uniting with Washington to combat imperialism in the only places it exists any more: Russia and China. The little pushback to the incessant drum beats for war came from voices such as Peter Beinart in the Times, Katrina vanden Heuvel in the Post, or from more isolationist conservative voices. However, these were few and far between.

There was essentially complete unanimity in presenting Russia (and not NATO) as the aggressor, with 87 of the 91 articles presenting the issue as such (four articles did not identify any entity as the aggressor). There was overwhelming support for sending in both huge quantities of what the Biden administration has termed “lethal aid” (i.e., weapons), and also deploying American troops in the region – a move that would rapidly escalate the threat of terminal nuclear war. As Bret Stephens wrote in the Times:

The best short-term response to Putin’s threats is the one the Biden administration is at last beginning to consider: The permanent deployment, in large numbers, of U.S. forces to frontline NATO states, from Estonia to Romania. Arms shipments to Kyiv, which so far are being measured in pounds, not tons, need to become a full-scale airlift.

The Post went much further, however, with one column demanding that the U.S. send around 85,000 soldiers to the region immediately, a figure that it said must be matched by other NATO members as well.

However, the Journal went furthest of all, calling for the U.S. to be turned into a global military state in order to fight two world wars at once. With more than a hint of delight, columnist Walter Russell Mead claimed:

Military budgets will have to grow as the U.S. increases its capacity against both Russia and China. The fantasies of withdrawing from some regions to focus on others will have to be set aside; Europe, the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America all require more American and allied focus and attention, even as we continue to gear up in the Indo-Pacific. The U.S. will have to spend less time inspecting the moral shortcomings of potential allies and more time thinking about how it can deepen its relationships with them.

A sitting US Senator said on live tv today that use of first strikes nukes wasn’t off the table and I’m not sure why more people aren’t freaking out about that 😳

— Jason Call for Congress (@CallForCongress) January 25, 2022

A long history and a broken promise

Context, it is said, is everything. The U.S. government’s view of the situation is that Russia is a perennially destabilizing influence. Putin, who has previously stated that Ukraine is “not a country,” has funded separatist groups in the Donbass region, illegally annexed Crimea, and bombards Ukraine with propaganda on a daily basis. From a war in Georgia to sending troops into Kazakhstan to quell a recent uprising, Russia is fighting a rearguard action to prevent the spread of democracy. It has also taken a confrontational stance to the U.S., hacking the 2016 and 2020 elections to help its preferred candidate.

However, many Russians would dispute these claims and begin the story in the ninth century with the Kievan Rus Federation, a nation whose capital was Kiev and from where the word “Russia” comes from. Fast forward a thousand years, and the broken promises made by the U.S. government to the U.S.S.R. also figure prominently. The first Bush administration, as well as the governments of West Germany and Great Britain, all assured Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO would never expand “one inch” to the east of Germany. This, of course, proved a promise made to be broken, and the anti-Russian military alliance has advanced across Eastern Europe, now including three former Soviet Republics that border Russia.

The U.S. has been extremely active in Ukraine’s domestic affairs, as Russian-American journalist Yasha Levine has highlighted, forcing the government to hike gas prices and raise taxes on alcohol and cigarettes. It has also bankrolled NGOs and local media outlets and threatened to jail Ukrainian oligarchs if further American demands were not met.

Washington’s role in the 2013-2014 Maidan Revolution, however, is the clearest example of American interference. Trying to play the two blocs off against each other, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych negotiated with both the European Union and with Russia on trade deals at the same time. In the end, he chose the superior Russian offer. Instead of accepting defeat, however, the West immediately began organizing a coup, funding and supporting street protests across the country. Senior U.S. officials like Senator John McCain and Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland flew to Ukraine to lead the demonstrations, the latter even famously handing out cookies to protestors in Independence Square in Kiev. Yanukovych was eventually overthrown in February 2014.

That the Maidan affair was organized, at least in part, by the U.S. is not in doubt. Indeed, leaked audio of Nuland talking with U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt showed that Washington effectively hand-picked Ukraine’s next government. “I don’t think Klitch should go into the government. I don’t think it is necessary. I don’t think it is a good idea,” Nuland can be heard saying, referring to the boxer-turned-politician Vitali Klitschko. “I think Yats [Arseniy Yatsenyuk] is the guy who has got the economic experience, the governing experience,” she continued. The two also discussed plans for implementing the new administration. Sure enough, less than one month after the audio leaked, Yatsenyuk became the next prime minister.

Since 2014, the Ukrainian government has pursued a campaign of privatization, as well as entering into deals with the E.U. that Yanukovych previously rejected. It has also aggressively purged the Russian language from schools and media, jailed opposition politicians, and shut down media outlets opposing it. Around one-third of Ukrainians speak Russian as their first language.

This context was barely referenced in the three newspapers; but, when it was, it was usually described in glowing terms. The Washington Post claimed that the Ukraine-Russia trade deal amounted to a Russian “invasion of Ukraine” and was simply Putin’s effort to “bribe Ukraine with an offer of $15 billion in loans and lower prices for gas.” The Wall Street Journal defamed Yanukovych as merely “Mr. Putin’s puppet.” Meanwhile, The New York Times cheered on what it approvingly called “the process of Ukrainization” as “the Russian language is being pushed out of schools and Russian television out of the media space.” The Times currently accuses China of doing something very similar in its western province of Xinjiang, denouncing the process as a “genocide.”

Not seeing fascism where it is – and seeing it where it’s not

The Maidan Revolution’s muscle was provided by far-right paramilitaries like the infamous Azov Battalion, a Neo-Nazi militia that has now been incorporated into the Ukrainian military. The U.S. government channeled huge amounts of money and resources to these groups, with fascist leaders like Oleh Tyahnybok sharing a stage with McCain and Nuland. Nuland’s leaked audio makes clear that she held some influence over Tyahnybok and his forces. Since at least 2015, the CIA has been directly training fascist militias inside the country.

Today, Ukraine has openly Nazi elements within its government, which has passed laws designating World War II-era fascist Ukrainian death squads that perpetrated the Holocaust as heroes and freedom fighters. Every January 1 in Kiev there is a large torchlight march to honor the Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera, with chants of “Jews out” being very common. There are now hundreds of monuments to fascist collaborators all over the country.

For two years in a row now, Ukraine and the United States have been the only countries to vote against resolutions “combating glorification of Nazism, neo-Nazism and other practices that contribute to fueling contemporary forms of racism.” The U.S. government calls the resolutions “Russian disinformation.”

Blowback: An Inside Look at How US-Funded Fascists in Ukraine Mentor US White Supremacists

The three newspapers studied solved the problem of Ukraine’s troubling fascist links by simply not mentioning them – even in articles where reporters appeared to be embedded with the Ukrainian military, a hotbed of far-right organizing. Only in one article in the sample of 91 – a calm and thoughtful Washington Post op-ed by alternative-media journalist Branko Marcetic – was it mentioned at all. And judging by the comments section underneath it, his thoughts were received with little short of rage from the Post’s readership.

Boot, an infamously hawkish columnist, might have obliquely referenced these bothersome facts when he wrote that “In [Putin’s] telling, nefarious foreign powers, ‘radicals’ and ‘neo-Nazis’ pursuing an ‘anti-Russia project’ have sought to lure Ukrainians from their rightful place under Moscow’s wing,” but immediately brushed this off as “incessant regime propaganda.” Apart from that, there was no mention of the far-right. On the contrary, the Ukrainian government was largely portrayed as a laudable, fledgling democracy fighting for survival.

This is not to say that there were no mentions of Nazis. In fact, the press is full of them. Over 10% of the articles studied directly or indirectly compared Vladimir Putin to Hitler. For example, The Washington Post’s editorial board began their January 8 editorial on Ukraine thus:

A brutal dictator, having staked a claim to power based on conspiracy theories and promises of imperial restoration, rebuilds his military. He begins threatening to seize his neighbors’ territory, blames democracies for the crisis and demands that, to solve it, they must rewrite the rules of international politics — and redraw the map — to suit him. The democracies agree to peace talks, hoping, as they must, to avoid war without unduly rewarding aggression.

What happened next at Munich in 1938 is a matter of history: Britain and France traded a piece of Czechoslovakia to Adolf Hitler’s Germany in return for his false pledge not to make war.

It continued throughout to hammer home the idea that Putin = Hitler. Editorials are supposed to represent the collective wisdom of the senior staff, and set the tone for the rest of the reporting team and across the wider media landscape. Thus, the editorial board were making their feelings about what sort of coverage was required very clear.

The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal both regularly warned against the “appeasement” of Putin – a term usually reserved for the period of Western soft collaboration with Hitler’s regime before they changed track and opposed it. Earlier this week, the Times claimed that the world was “holding its breath waiting for Vladimir Putin to bite off a slice of Ukraine the way another revanchist European dictator once took a slice of Czechoslovakia” – another reference to Hitler. The message conveyed was simple: this is a repeat of World War II.

While Vladimir Putin could reasonably be called many things, Hitler-incarnate is stretching credulity. Unable to introduce relevant context that would deviate from this line, however, the armchair generals demanding war took to psychoanalyzing the Russian leader, as well as throwing all manner of insults his way. In just this three-week sample, Putin was declared an “evil dictator,” a “thug,” a “KGB sociopath,” and a “pathetic throwback.” Longtime Times columnist Thomas Friedman, in his unique style, described him as “America’s ex-boyfriend-from-hell,” continuing:

Putin is a one-man psychodrama, with a giant inferiority complex toward America that leaves him always stalking the world with a chip on his shoulder so big it’s amazing he can fit through any door.

Yet for all the psychoanalysis, it was Western pundits who appeared to be in their own heads, and were obsessed with the supposed need to look tough in front of Putin. Citing South Carolina congressman Joe Wilson (R-SC), the Post declared that “weakness is provocative.” “Vladimir Putin does not think like we do,” warned hawkish former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul, going on to assert that Putin saw destroying America and the global order as his “sacred destiny.”

Putin’s allegation that Ukraine was being groomed to join a hostile military alliance was met with contempt and derision in Western media. “None of the fears the Kremlin’s propaganda play (sic) on have any foundation in reality… No one was seriously contemplating NATO membership for Ukraine or Georgia. Plans for U.S. missiles in eastern Ukraine targeting Russia are pure fantasy,” a Post opinion piece informed its readers last week, its editorial board then adding:

This entire crisis has been manufactured by Mr. Putin as part of his long-range effort to thwart the democratic development and growing Western orientation of Ukraine and restore Russian hegemony over the former Soviet empire. It has nothing to do with expansion by NATO, whose founding treaty authorizes only defensive military action.

Readers in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Somalia or Libya might have differing ideas about whether NATO has been used purely defensively.

Yet, at the same time as categorically denying Ukraine would join NATO, the articles studied dismissed Putin’s core request that the alliance simply put that in writing as “silly” “extravagant” “unrealistic” and a “nonstater” – something that is hard to understand if this was all that was needed to avert World War III. In reality, NATO is indeed looking to admit both Ukraine and Georgia, having promised to both countries that they would do so as far back as 2008.

Pipeline politics and cracks in the NATO alliance

Last week, Washington Post columnist Daniel Drezner proclaimed that “Putin has succeeded in creating his worst strategic outcome: unifying NATO.” Yet this seems wishful thinking. Germany and France, the most powerful nations in Western Europe, have both openly expressed reluctance to escalate the situation. The German government did not allow British warplanes carrying weapons to Ukraine to pass over its airspace, and it blocked shipments of German-made arms from the Baltic States to Ukraine. Even more significantly, Kay-Achim Schönbach, vice-admiral of the German Navy, publicly condemned what he saw as a reckless buildup of tensions. Schönbach stated that the West was refusing to give Putin even a modicum of respect and that we should accept the Crimea annexation as a fait accompli. For this outburst, he was forced to resign.

Across the border in France, President Emmanuel Macron is so alarmed by the U.S./U.K. push to escalate tensions that he has called on the EU to start its own negotiations with Russia – negotiations that exclude the U.S. and U.K. Germany and France were written off as “appeasers” of a dictator by The Washington Post, and as puppets of Putin and of Chinese premier Xi Jinping by The Wall Street Journal.

Much of the EU’s reluctance to get behind an American-led war on Russia is attributable to their energy dependence on Moscow. Currently, Russia supplies nearly half of the EU’s gas and around one-quarter of its oil. This is likely only to increase with the imminent completion of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which runs undersea from Russia’s Baltic coast directly to northern Germany. The United States has repeatedly demanded Europe cancel this project, insisting that Europe service its energy needs from Middle Eastern dictatorships under U.S. control or directly from the U.S., at around four times the price of Russian gas. The U.S. is currently considering placing sanctions on German companies involved in Nord Stream 2.

“If Biden can’t stand up to Germany, how can he stand up to Putin?,” asked one Washington Post columnist last week, the same article demanding that Germany be “punished” with the removal of U.S. troops from its territories. “Why should Germany…continue to be rewarded with the economic benefit of U.S. bases?” the writer asked, framing the American occupation in a light that some readers might not share.

Meanwhile, the climate change skeptic board of The Wall Street Journal took the opportunity to assert that Russia had infiltrated the European environmental movement, convicing the movement to take up stupid positions like being against fracking or coal plants. This was, they claimed, all part of a successful effort to keep Europe dependent on Russian gas.

The war machine’s checklist

If Russian troop movements are mostly ordinary and not dissimilar to those that have happened almost every year since 2014, what explains the media circus?

To answer this question, we must examine a policy report prepared for Biden in March by NATO think tank The Atlantic Council. Titled “Biden and Ukraine: A strategy for the new administration,” it lays out a set of goals for the new president to achieve; under its “key recommendations” headline, it outlines a number of actions the Biden government should take. Among them are included: “Work[ing] with Congress to increase military assistance to Ukraine to $500 million per year;” “Deepen Ukraine’s integration with NATO” by potentially “establishing a permanent U.S. military presence” in the country; and “launching a NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP) for Ukraine,” if Russia remains “intransigent.” “Stay the course on Nord Stream 2” and a “Strategic approach to sanctions” are also included on the list of key bullet points, as well as supporting a host of free-market privatization drives inside Ukraine.

Compiled by former U.S. ambassadors to Ukraine, Poland and Russia, as well as the ex-deputy secretary general of NATO, the report’s recommendations serve almost as a checklist of everything the U.S. is currently trying to push through. Last week, Congress began rushing through an emergency $500 million weapons bill that would make Ukraine the world’s third highest recipient of U.S. arms, rivaled only by Egypt and Israel. The U.S. is sending thousands of troops to Eastern Europe; its Nord Stream 2 opposition remains as loud as ever; while the Ukrainian government under President Volodymyr Zelensky is indeed moving towards the sort of economic shock therapy the Atlantic Council wants to see. All this might lead a cynic to see the current crisis as little more than an excuse to force through long-held U.S. establishment goals.

“We don’t need this panic”

None of this helps ordinary people living in the country White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki has termed “our Eastern flank.” Ukrainians are concerned with the dire economic situation, which has plunged over half the country into poverty – the highest rate anywhere in Europe. Inflation and the rising cost of heating and electricity are the highest concerns among citizens, according to a poll conducted by the U.S. government-sponsored International Republican Institute. The same poll found the country was split on where it wants to head politically, with 54% wishing to join NATO and 58% the European Union, but significant minorities preferring more integration with Russia. Ukrainians perceive both Russia (63% of the population) and the United States (51%) to be a threat, according to a recent report from a NATO-aligned think tank.

Meanwhile in the United States, despite the media saber-rattling, there is limited public appetite for any conflict with Russia. Last week, a Rasmussen poll found only 31% of Americans think U.S. troops should be sent to Ukraine, even if Russia launches an invasion. President Biden himself has even tried to pour cold water on the flames of war, claiming that the U.S. would not react to a “minor incursion” by Russia – a statement that outraged hawks in Washington.

War profiteers are clearly expecting increased orders. Last week, Raytheon CEO Greg Hayes confidently said, “I fully expect we’re going to see some benefit from [the Ukraine crisis].” Raytheon and Northrop Grumman stocks are currently approaching all-time highs. Weapons industry-funded media like Politico publish content wondering whether the U.S. should “rattle Putin’s cage,” and journalists at White House press conferences continue to goad the administration into more aggressive posturing.

President Zelensky himself has chastised Western press for their hyperbolic coverage of the situation. “The image that mass media creates is that we have troops on the roads, we have mobilization, people are leaving for places. That’s not the case. We don’t need this panic,” he said. Studying the opinion pages of America’s three most prestigious outlets suggests that Zelensky is right: nobody wants war, except for hawkish elements in the national security state and among the press that increasingly does its bidding.

Alan MacLeod is Senior Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent, as well as a number of academic articles. He has also contributed to FAIR.org, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, and Common Dreams.