Several of the more intriguing files released in the President John F. Kennedy assassination files have little to do with specific aspects of the assassination. Instead, they involve covert operations that were contextually related to possible theories that were initially entertained by investigators.

A special group of military generals and CIA officials met to discuss “sabotage operations” in Cuba on September 6, 1962. The group discussed “agricultural sabotage.”

General Marshall Carter suggested introducing “biological agents which would appear to be of natural origin” to destroy crops.

“General [Marshall] Carter emphasized the extreme sensitivity of any such operation and the disastrous results that would flow from something going wrong, particularly if there were obvious attribution to the U.S.,” according to top secret minutes from the meeting. Carter believed that, if subtle, such sabotage would succeed.

McGeorge Bundy, a national security adviser, was confident that any sabotage could be “made to appear as the result of local Cuban disaffection or of a natural disaster, but that we must avoid external activities such as release of chemicals, etc, unless they could be completely covered up.”

Over 2,800 files were released in the evening on October 27, as a result of the JFK Records Act from 1992. The law—passed after Oliver Stone’s “JFK” film—established a collection of “assassination records” at the National Archives and required all records be released no later than 25 years later.

But at the last moment, even though the CIA and FBI had plenty of time to prepare for this release, President Donald Trump allowed the agencies to invoke “national security” and put the 50 to 60 year-old files through yet another review. Parts may be censored, and the rest of the files may not be seen until April 26, 2018.

One report drafted by Phil Buchen, who served as White House counsel for President Gerald Ford, for a commission into CIA activities addresses the agency’s involvement in assassination plots of foreign leaders. It notes the commission was denied access to papers of special groups or special operating groups.

“The investigation is not complete with regard to the question of who, if anyone outside the CIA, authorized or directed the planning of any assassination attempts against foreign leaders. However, with particular reference to the plans directed against Fidel Castro, the investigation is sufficiently complete to show that plans were undertaken by the CIA.”

According to the report, the CIA discussed plans to assassinate Castro if he was visiting the United States. The CIA shipped arms from the U.S. to “persons in the Dominican Republic, who sought to assassinate Generalissimo Trujillo.”

The commission struggled to uncover evidence of CIA involvement in the assassination of Congo leader Patrice Lumumba in 1961. However, it confirmed the agency considered an assassination plot.

According to a “case officer,” who failed to keep his appointment to testify before the commission, Richard Bissell, the CIA deputy director of plans, “asked him to go to the Congo and there murder or arrange for the murder of Lumumba, and the case officer said that he told Bissell that he refused to be a party to such an act.”

The CIA also considered assassinating President Sukarno of Indonesia. Bissell told the commission the agency identified an “asset who it was felt might be recruited for this purpose.” But the plan never reached a point where the CIA thought it was “feasible.”

U.S. officials considered using members of the Mafia to kill Castro. In September 1960, a “syndicate member” from Chicago, Sam Giancana, was contacted. “An arrangement was made through Giancana for the CIA intermediary and his contact to meet with a ‘courier’ who was going back and forth to Havana. From information received back by the courier, the proposed operation appeared to be feasible and it was decided to obtain an official agency approval in this regard.”

“A figure of one hundred fifty thousand dollars was set by the agency as a payment to be made on completion of the operation and to be paid only to the principal or principals who would conduct the operation in Cuba.”

When the CIA advised Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy of this plan involving Giancana, he apparently wanted the CIA to consult the Department of Justice before they took such actions again. He was concerned that Giancana could not be prosecuted anymore because he “could immediately bring out the fact that the United States government had approached him to arrange for the assassination of Castro.”

Another document prepared by Buchen contains further details on anti-Castro plots. It contains details of “Operation Bounty,” which was to establish a “system of financial rewards, commensurate with position and stature, for killing or delivering alive known communists.

Leaflets, delivered by air, would contain names of Communist leaders. The next round of leaflets would “revise the names by job, i.e. cell leader, informer, party members, etc. They would contain the “amount of reward, how, and where it may be collected.” One final leaflet would indicate a reward of two cents if someone delivered the body of Castro.

General Edward Lansdale, a deputy assistant secretary for special operations, distributed an “action plan” in February 1962 that called a “special target” operation that could include “gangster elements” attacking police. “CW agents” [chemical weapons] should be fully considered.

There was a plan known as Task 33, a “Plan for Incapacitation of Sugar Workers,” that was completed in February. “Task as assigned was to develop a plan for incapacitating large sections of the sugar workers by the covert use of BW [biological weapons] or CW agents.”

A part of the Task 33 plan previously kept secret was released showing Lansdale proposed putting a majority of sugar workers out of action during the remainder of the harvest by introducing “non-lethal BW, insect-borne” agents. The Navy would conduct the biological attack. (Lansdale noted Robert Edwards at Fort Detrick, Maryland, and Cornelius Roosevelt at the CIA would provide biological weapons information for the suggested operation.)

Plans for military intervention, or a coup, always depended upon the belief within the U.S. government that a pretext could be created. As one top secret stated, “If we announced incident going in; that we were moving in to restore order and hold free elections and that we would withdraw from Cuba as soon as the new government advised that they had the capability to maintain order without further assistance,” it could probably be successful.

Plans for military intervention, or a coup, always depended upon the belief within the U.S. government that a pretext could be created. As one top secret stated, “If we announced incident going in; that we were moving in to restore order and hold free elections and that we would withdraw from Cuba as soon as the new government advised that they had the capability to maintain order without further assistance,” it could probably be successful.

The U.S. government did not think such covert operations would negatively impact world public opinion. Officials found the Soviet Union threat to be so severe that if they did not at least contemplate these actions in Cuba they may allow the Soviets to setup military bases in Cuba. Were that to happen, officials were prepared for World War III.

While the essence of planned operations against Castro and Cuba were known, the files offer vivid representations of flagrant and immoral disregard U.S. officials had for international law, sovereignty and human life. They reflect secrets the CIA and FBI were most intent on keeping from the public as long as possible.

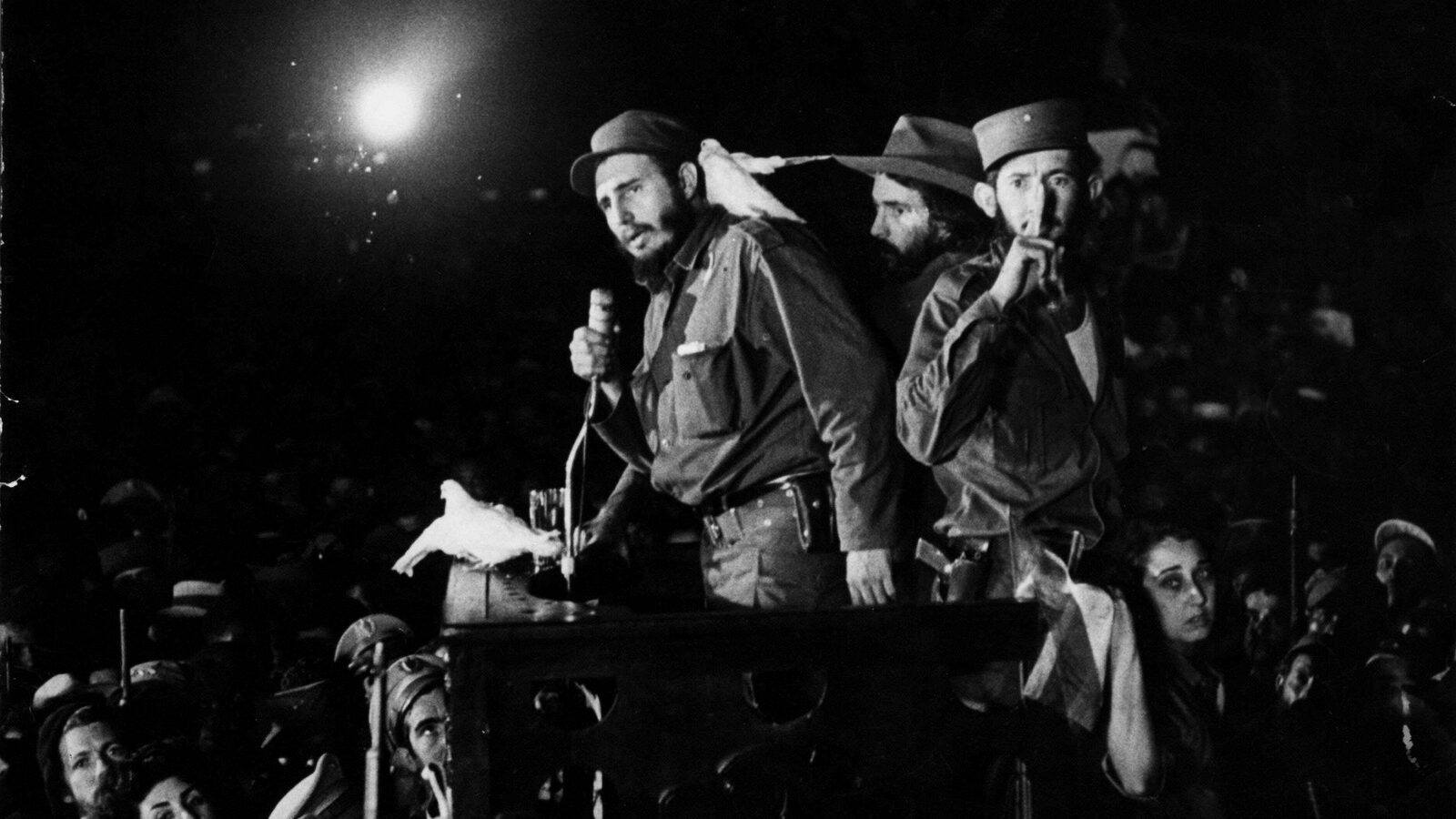

Top photo | In this Jan. 8, 1959 file photo, Cuba’s Fidel Castro speaks to supporters at the Batista military base “Columbia,” now known as Ciudad Libertad, in Cuba. (AP Photo)

Published in partnership with Shadowproof